Videos by American Songwriter

On September 27, 429 Records will release Note Of Hope, an album of Woody Guthrie’s writings set to music by artists like Lou Reed, Jackson Browne, Tom Morello and Pete Seeger, and spearheaded by Grammy-winning bassist Rob Wasserman. We spoke with bassist Wasserman about the ten years he spent working on the project, collaborating with Lou Reed, and whether or not Woody Guthrie would make a good rapper.

How did you get involved with the Note Of Hope album?

About 10 years ago, I was performing at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with Bob Weir–we were doing a tribute to Robert Johnson with a bunch of other musicians. I also did a solo performance the next day and Nora Guthrie basically came up to me and asked if I’d like to work with her dad’s words and come up with a more stripped down bass and voice project. She had a vision for something a little more sparse and spontaneous .

I was so happy and excited because actually for years I was a huge Woody Guthrie appreciator — I read his book and was really inspired by him when I was a young kid, before I even played music, and it was sort of unusual that that would happen. Especially coming up to an instrumentalist after an hour bass performance, but I guess she just heard something that I could take to her words. They were unpublished, these journals, and then she started sending me words after that, and that’s how it all started.

What was it that drew you to him? Because his music can be very plain.

It was more about his spirit. I read Bound For Glory when I was 15 or 16, and I was very free spirited back then. I had dabbled in the guitar and I didn’t know any songs. But I listened to all his music all the time back then, before I listened to jazz or rock or anything else. I have no idea why. I also listened to all related people that he worked with, like Sonny Terry. I’m not really a word person, even though I’ve worked with all these renowned lyricists, but I seem to always find a way to make a couple lines with people I work with. I help support the words, so I think she must have heard that. She’s very instinctive.

This took a long time because I’ve decided to work on it myself between touring and other projects. Sometimes it would be year between tracks and I wasn’t even sure who would play, and she had ideas about who would play. This went on and on and on. We invited three or four people we never used. It evolved but we tried to keep the real spirit of the project. But little changes went along, I’ve always wanted to make it through these words in the songs, but some of them were 20 pages long and it’s very hard to get a lyric out of 20 pages without editing. You know, it’s challenging for everybody, because a lot of these people I invited didn’t want to just read the words if they were singers. But some of them only wanted to read the words like Studs Terkel and Pete Seeger.

So it was an extremely challenging project. I had no idea what I was getting into. We changed our minds a few times. Sometimes she thought I should do more with just a bass voice and no other instruments, but you know we didn’t really do that. We ended up with every song having different instrumentation. And I wrote one bass solo because she really wanted me to feature myself obviously and then I got the idea to do something different, so we made it an orchestral piece. But I wrote the solo after I read the words. She wanted me to write something being directly inspired by some of his words. So that became the title of the album– Note of Hope.

For the spoken word tracks, it’s like a movie for your mind of sorts.

Yeah, what really is interesting to me is the words. Some of them date to the late 40’s and early 50’s. Most of the subject matter sounds like what were talking about right now, politically and it’s sort of eerie in that sense. It’s like he’s come back to life, or foresaw the future in someway or you know, history is repeating itself at the same exact time with the wars and the dishonesty in government. And he’s just sitting there in these coffee shops writing about everyday life, sometimes he’s writing about his wife, like in the Jackson Browne song. Other times he’s writing some pretty provocative stuf,f and a lot of it’s political but it’s not preachy. I think his words are brilliant.

Did you work with the artists on an arrangement, or would they come in with the song that they wanted to do in mind?

I wanted to write the music with everyone, but it had to be really flexible. Sort of the way I am as a bass player. It helps to be a bass player with these things because you’re used to so many different ways of making music happen. But quite a few of the artists–we colloborated in the studio. But some of them were very spontaneous like the Chris Whitley, we had just been playing with Bob Weir back in the day. I introduced him to that whole world. So were just jamming and we did a tune that was a real improv thing, and basically after that we just jammed. It came out very raw and spontaneous.

Who came in with a song firmly written?

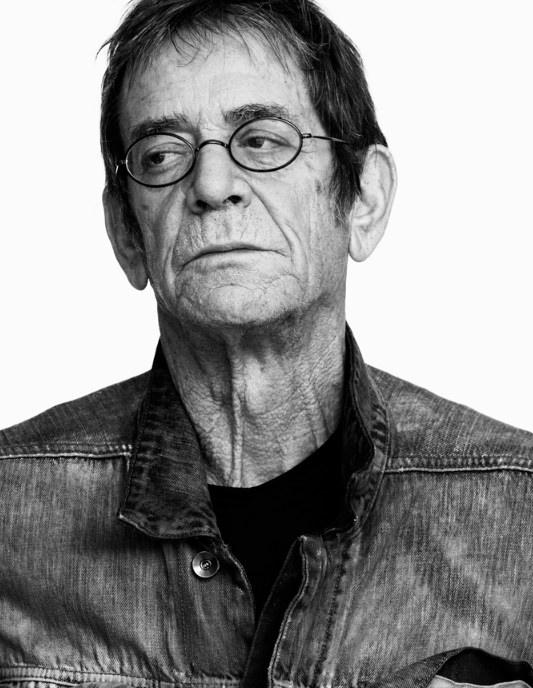

Lou Reed was one. He’s a very self- determined writer. He asked if it was okay to edit the lyrics and the words, because the were very raw, so he re-wrote some of them. We had played together for many years so there was already kind of a muiscal chemistry going. So there were no struggles with him. In fact I just got off the road from a couple months in Europe with him. I’ve been working with him 25 years. I just felt he would be a natural for the record because I wanted to keep it mainly to New York artists. I jthought the spirit of things needed to be from that area.

But Lou and I colloborated, I didn’t ask for credit from him, but he and I put that together. He came up with the chords and the song, and he does work with people. He’ll write the song but then he’ll work with you on the organizational stuff. I just wanted to make it really interesting from my perspective. I made a real dramatic piece that went with the words.

Nellie Mckay, she’s a great artist and she doesn’t really colloborate. She was very much ready. That was the one that was the most prepared of all of them, I think. There was one Tom Morello wrote that was also prepared, but it had a little looser feel. And that was fun for me because I played more of a bass guitar part and his drummer never played with an electric up-right bass player before. So it was fun for them to do something different. And they got me to sing and shout in the background and I don’t ever do that. I think those were the ones that were prepared before.

Madeleine Peyroux wrote hers too. She’s pretty self-determined. She came up with some really good melody and I just decided when someone really comes up with something before that’s really good..

But mostly this record was a collaboration between me and Nora. And the funny part, if there is a funny part, is when you have this much latitude and you don’t have a deadline, it’s hard to want to stop. It sadly could have gone on for another ten years and made another couple records of the same thing. And she realized it was time. She kept joking that she was gonna retire and I gotta end this in time. And she and Steve Rosenthal, who owns this place called the Magic Shop in New York came in to help make some masters. I got back from a tour and they said to me, “we think the record is done.” We’ve got a lot of music here and they were convinced that it was done. So I decided to wrap it up. That’s the one benefit of normal records — you have to make deadlines. But with Nora we didn’t have a deadline so sometimes it just really stretched out. But also I was just looking for that other right artist. It was hard to finally say, “this is finished.” But we did, and I’m glad you know, because it would be sad if we missed his hundredth birthday year.

What’s the story behind the Jackson Browne track? It’s 14 minutes long. Was he intimidated by all that material?

No, not at all. He was the opposite of intimidated. He embraced it. I found him in a show I was playing in LA, I was actually performing with Rickie Lee Jones a couple years ago and he came up to me and said hi and told me he loved my bass playing and all that. And I was in the process of getting people to do the record and I invited him right then. And we showed him some words. He chose the words that were around 30 pages long. And I don’t think he really realized what it might mean to do a song that was that long. Nora told him he could edit if he wanted, but he didn’t really want to edit much. He loved the words so much and the story, he didn’t want to chop it down or shorten it much. We did do a four minute thing for radio so there’s a chance someone may hear the song outside the record. He never wanted to edit the song for the record, and you know it’s 25% of the record–15 minutes long. But we both love the tune and somehow we made up the music and the melody together on our first day jamming in the studio.

There’s a photograph, I think it’s in the record with a couple music stands with all the words taped over them–a massive amount of words, and he really got into it. To this day he says that when he plays the song for his friends, they sit there and after ten minutes they’re still sitting there and they’re into it. But at the end they’re wondering if they’ve really been listening to music for a whole day. They’re surprised at how intense and long it is. Even though it is long, it doesn’t really feel long when you get into it, it really grabs you. It could have been a spoken word piece because there were so many words, but to his credit, he wanted to sing it, so he turned it into a song.

Michael Franti’s piece is kind of rap meets spoken word, and it’s about sex, which is funny. Would Woody Guthrie be into rap if he was around today? At first you’d think yes of course, because it’s such a vibrant art form, but maybe he would have objected to the negativity in the lyrics. What do you think?

I think he might even be a rapper if he was around today. You know like the Eminem of today, except rapping about other people instead of himself. He was such an observer of everybody around him and what was going on. He used very simple chordal progressions and made up simple melodies, but his things were the words. So he definitely could have been into rap, if not one himself. Yet, he could have gotten into spoken word. And he didn’t get into that as much, he sang his words.

But I think he’d really dig the Franti piece. To me it’s like a real gumbo sort of mixture of so many musical styles that I ended up throwing in there. It started with rap in the studio with me and Michael, and basically he made up a drum beat and I made up the melody. The bass line is the melody. And that was it and we overdubbed the other stuff and he just rapped. But he rapped perfectly. If you think about it, Woody Guthrie could well have been reborn as a rapper. It might not be a bad idea to have another project some day. Maybe some rapper will take it and do a whole record like that.

3 Comments

Leave a Reply