This article appears in the November/December 2015 issue, now available on newsstands.

Videos by American Songwriter

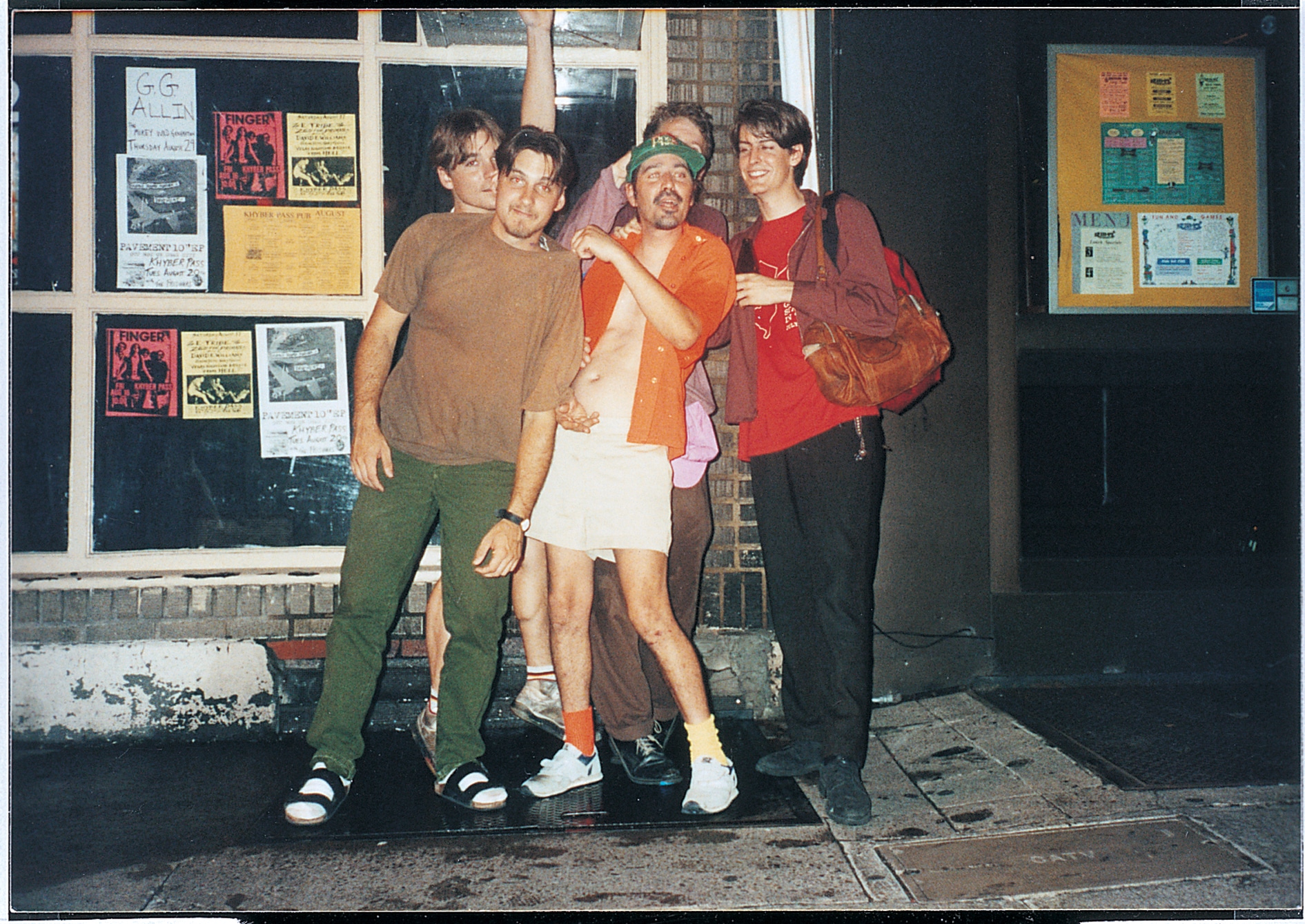

Pay to the order of: _______Pavement_____

Pavement made their parents launder money.

Back when the iconic ’90s band was just starting out, they would accrue great piles of cash on the road. When all those bills grew too unwieldy to manage, for reasons of pragmatism as well as security they would devise creative ways to deal with the problem. “I remember making my mom go to the bank with $8,000 of Pavement money,” recalls Bob Nastanovich, the band’s auxiliary drummer, multi-instrumentalist, hype man, and occasional tour manager. “The band was standing there in line with my mom as she deposited our $8,000 in ones, fives, tens, and twenties, and then she would write the band a check. She kinda sorta laundered money for us.”

Nastanovich laughs genially at the memory of five road-weary musicians engaged in such a petty crime, but that was life for a midlevel rock band in the early 1990s, even for one that would define the indie underground for decades to come. Acclaim greeted them almost from their first notes, and while that meant more ticket sales and a long line to the merch table, it barely changed the way Pavement operated on the road and off. Rather than a bus, they traveled by car and, later, by a van they nicknamed Gina. Rather than Square readers attached to iPhones, they had suitcases and fannypacks crammed with bills, which they handed off to parents for deposit.

“That’s one thing about Pavement that people don’t realize,” Nastanovich continues. “We had six members of the band and twelve unusually cool parents. They would come see the band, and we’d hang out with them. It made the whole experience that much more bearable, as corny as that may sound. My mom was cool enough to make that deposit and write us that check.

“She is still that cool, but I wouldn’t want to ask her to do it now.”

///

Historically viewed as standard-bearers for ’90s slacker rock, a loose and jangly variation on punk that rejected flat-out aggression for defensive irony, Pavement were never quite the portrayed in the mainstream press. They worked hard in the studio and on the road, but made it look easy. Throughout their long history as both a band and an ex-band, they rebelled against the strictures of the rock-industrial system, as much out of necessity as for aesthetic integrity. Their business practices, much like there music, were essentially DIY: endlessly clever, inventive, cheeky, and even at times possibly criminal. They made up a new set of rules as they went along, essentially redefining what it meant to be a special new band and, later, what it meant to be indie lifers.

Their first real business decision—made before Nastanovich joined the band, before they released their landmark Slanted & Enchanted, before they were even really a band at all—was also one of their most fortuitous. Co-founders Stephen Malkmus (billed mysteriously as S.M.) and Scott Kannberg (a.k.a. Spiral Stairs) had a few songs they had put together and needed a place to record them. Their hometown of Stockton, California, had two viable options: one a professional studio that would take a Brinks job for the duo to afford, the other a makeshift space in some dude’s house, small and cramped but—here’s the kicker—cheap.

Guess which one they chose.

Kannberg and Malkmus put together Pavement’s first EP at Louder Than You Think studio, which was owned by a hippie burnout, ingenious inventor, and alcoholic named Gary Young. About ten years their senior, he would become the band’s original drummer simply by virtue of being there and having a pair of sticks. Moreover, those early sessions would crystalize the Pavement sound as something fizzy and unpredictable: Slay Tracks (1933-1969) takes elements familiar from the punk rock beloved by Kannberg and Malkmus and bent them into new shapes, the better to convey the concerns of a new generation more aware of those elements as conventions. It was a new kind of alienation, even if the trio didn’t quite know it yet.

Still, Pavement was slow to begin. Kannberg sent out copies of Slay Tracks—and, later, Demolition Plot J-7 and Perfect Sound Forever—to radio programmers and zine editors around the country, and the response was so deafening and positive that they were almost forced to become a touring entity. That meant adding Mark Ibold on bass and Nastanovich as a second drummer.

A former bus driver and one of Malkmus’ roommates, Nastanovich was originally hired to drive the van, but eventually he became a performer himself. “On the very first tour we ever did, I was just supposed to be the tour manager,” he says. “We went to practice at Gary’s parents’ house in Mamaroneck, New York, and Stephen took me aside and told me that I better get a couple of drums because Gary’s incompetent sometimes. I had not really ever played drums, and I still haven’t learned to play kickdrum. But I had to make sure somebody was keeping time.”

While their first shows were chaotic and sloppy, eventually Pavement developed some chops and transformed into a stage act with their own unique dynamic, one that could swing perilously from artfully disjointed to genuinely intense. It was up to Nastanovich to keep the whole thing on the rails, but “I had already been the bus terminal manager in New York City, so managing a bunch of derelicts on the American highway was not that difficult of a chore. My nickname was Harsh Harold because I bossed them around. They needed bossing.”

Eventually Young left the band—or was booted, depending on who is telling the story—and was replaced by Steve West. The band collected money from the door and the merch table in a big black duffle bag, which they stashed under Nastanovich’s floor tom during shows. Typically, they’d be traveling with tens of thousands of dollars in the truck of a car, like gangsters running Prohibition hooch.

“Or pranksters,” laughs Nastanovich.

///

Perhaps the next major business decision came after Pavement had recorded what would be their full-length debut—a thorny, gnarly, often hilarious collection of tunes called Slanted & Enchanted. Drag City Records, then a fledgling Chicago indie label started by a clerk at Reckless Records, had released Perfect Sound Forever, but for their first album, Pavement jumped ship to Matador Records. Band lore has it that they based the decision on two facts: First, Matador had a fax machine, and second, Matador was in New York. The first is likely a joke, but the second is true. “Dan Koretsky at Drag City said he’d go buy a fax machine,” says Kannberg. “But Stephen was living in New York at the time and he would see those Matador people all the time. So it seemed natural to go with them.”

Pavement would spend the rest of their career on Matador, releasing five albums throughout the 1990s and touring almost constantly. Yet, even as they grew more popular and played to larger and larger crowds around the world, they more or less operated as they always had. “We never had a manager,” Kannberg admits. “Matador was acting like our manager. We never paid them but they made money off of us. It helped us make more money and keep control over everything.”

Overseas, Pavement weren’t so lucky. The band signed with Big Cat Records in England, home of Cop Shoot Cop, Lotion, and Foetus, but it was no Matador. “They did a good job getting Pavement on the map over there,” Kannberg admits, “but they were releasing records, making money off them, and never paying us. We didn’t get Slanted back until the reunion tour [in 2000]. So we made some good decisions and some bad decisions.”

During a decade famously defined by the tensions between the underground and the mainstream, Pavement fought to avoid drowning in Nirvana’s wake. They strove to be more than just another buzz band that flickered and died in an album or two, and it was easy to remain indie when there was minimal major-label interest. “We were never approached,” insists Kannberg. “Our records weren’t really major-label material. Nobody was knocking down our door, I guess because we had a reputation for being independent.” Nor did Pavement give much thought to pursuing a contract with a larger label: “They might have given us a bigger advance, but it was a bit scary to us. You could end up having no control over anything in your band.”

///

Fast forward through more albums and EPs, countless tours in America and abroad, one Lollapalooza gig, and the gradual onset of fatigue and tension. In November 1999 Pavement played their final show at Brixton Academy in London, then broke up—or went on hiatus, or just stopped playing together, or whatever. Yet, as with so many indie bands from the ’80s and ’90s, their afterlife has been filled with reissues, reassessments, and reunions.

In 2002 Matador launched an ambitious campaign to expand all five albums with b-sides, alternate takes, live tracks, stray covers, and wonky experiments. “I had most of the old tapes sitting around my house, and I really wanted to figure out how to get rid of them,” says Kannberg, the band’s unofficial archivist. “We had a lot of fun going through them, and it was so successful that we did it for each of our records, except for Terror Twilight. There just wasn’t a whole lot of extra material.”

In August 2015, Matador re-packaged those rarities—sans album tracks—as The Secret History Vol. 1. “We did try to make them different from the reissue series so it would be something special and new fans could feel like they’re getting something new,” says Kannberg. “We had to reorder the tracks, because if we had done it the same way as the CDs, it wouldn’t have fit on four LP sides. A lot of people don’t have that stuff on vinyl and supposedly they really wanted it. So hopefully a lot of people are pretty happy.”

“I was completely unaware of the idea,” says Nastanovich with a laugh.

///

Along with the string of reissues comes that event that is now obligatory in the life of any beloved band from any decade: the dreaded reunion tour. After the band had lain dormant for a decade—which is just as long as they were originally active—the members of Pavement announced a reunion show in Central Park, scheduled for September 2010. The show sold out in less than five minutes, and subsequent festival dates were planned, along with an appearance on The Colbert Report and a double-album greatest hits titled Quarantine The Past: The Best Of Pavement. It was a victory lap of sorts, but also a good way to introduce the band to a new generation of fans who only knew the music in the past tense.

As of this writing, no future reunion dates are planned, although at least two members would be up for it. “I’m constantly trying to get the band to do something interesting again,” says Kannberg, “and I think everybody is up for it—except for one person!” Adds Nastanovich: “If it were me calling the shots, what I would do is I would pick a certain number of songs—like, maybe 30 pavement songs. Don’t be afraid to play deeper cuts. And we’d play ten or fifteen shows a year in different parts of the world. I think that would be fun, but it’s not going to happen.”

But who really knows what the future holds? Pavement have been westing by musket and sextet for a quarter-century now, and if they’re not feeling their way blindly, then they’re at least making business decisions based on what allows them most control over their own collective destiny. “The creative process is tantamount,” says Nastanovich. “Everything that goes on behind the scenes should make you happy and ensure you have time to keep making stuff up.”