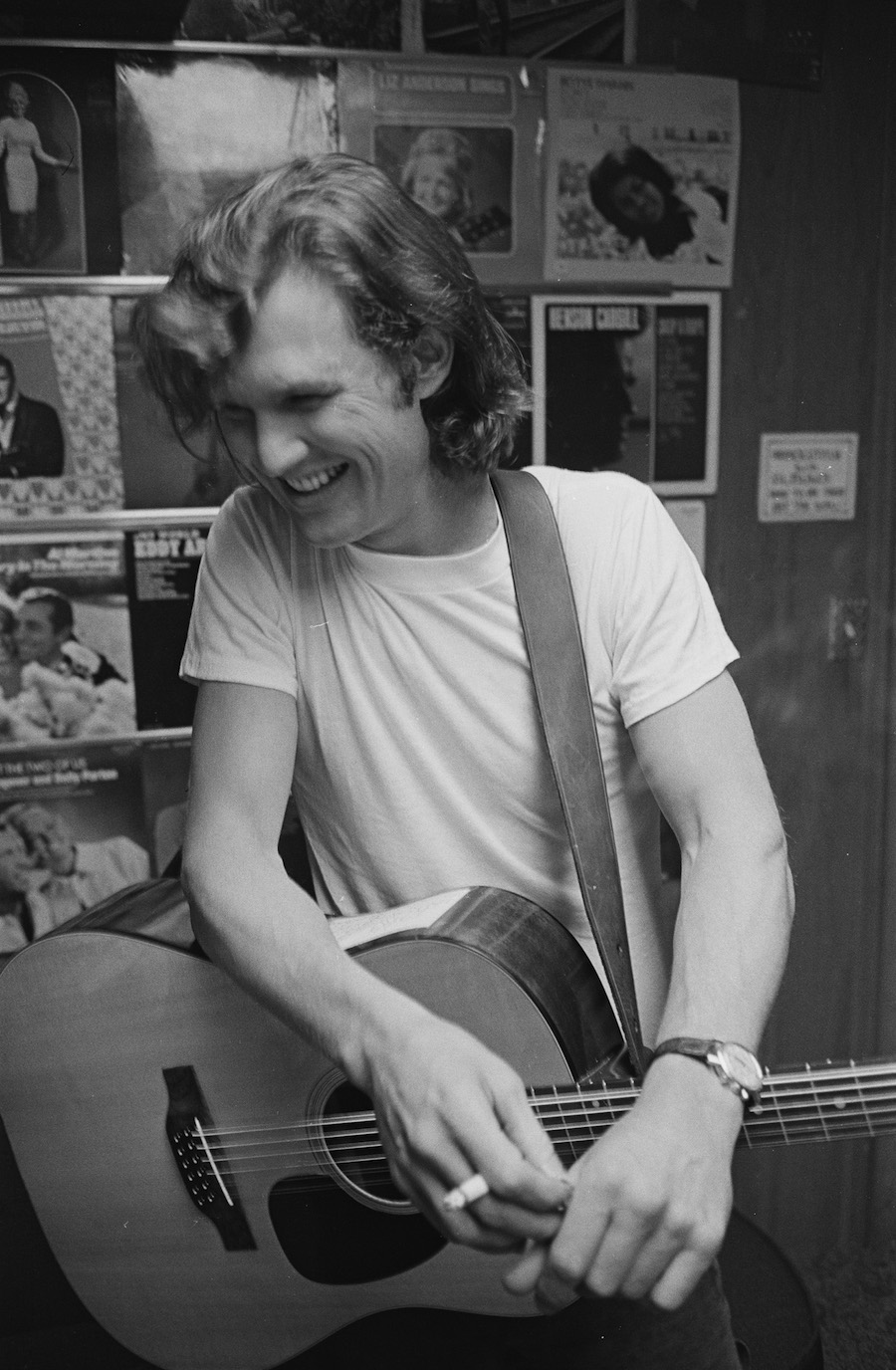

Two months after the Isle of Wight Festival, on October 3, Kristofferson found himself in friendlier territory: the Big Sur Folk Festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, where the pivotal Monterey Pop Festival had been held three years earlier. Folk fans, accustomed to Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Tim Hardin, were open to the raspy vocals and elliptical metaphors, even when Kristofferson dressed them up in hillbilly clothes. His full set from that day has been released for the first time as a bonus disc on the new Complete Collection, and Kristofferson sounds less combative and more generous on this version of “Me And Bobby McGee.”

Videos by American Songwriter

At Big Sur, you could hear the wonderful particulars of the verses, which described two bohemian hitchhikers with empty pockets and cheerful optimism. The narrator was “feeling nearly faded as my jeans,” before a truck driver picked them up, and soon, “with them windshield wipers slapping time and Bobby clapping hands,” they sang “every song that driver knew.” You needed to hear these verse details to appreciate the refrain, for only in the context of the hitchhikers’ happy-go-lucky poverty did the phrase “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose” sound like hard-won wisdom rather than glib sentiment. And you needed the aphorism to make the details resonate beyond mere description.

That was Kristofferson’s genius: to link specific imagery to universal catch-phrases — and to make those aphorisms too paradoxical for comfort. After all, what kind of freedom is it to be so poor that there’s nothing left to lose? Yes, there’s something liberating about traveling without obligations or possessions, but what if you desire the freedom to find a home, as Bobby does in the last verse, or find a vocation, as the narrator apparently has? And isn’t there always something left to lose? Doesn’t the narrator regret losing Bobby in Salinas? Kristofferson would pursue the elusive essence of freedom for the rest of his career.

“I learned from Kris that you could write very specifically and with your own sense of poetry and have it be legitimate,” Rosanne Cash says. “More and more specific is where I wanted to go, because of him. But his visceral imagery — the rooms, houses, bars, streets and all the little artifacts of life — was combined with his unexpected and sharp turns of phrase — all combined in loping melodies and tight rhyme schemes. He made the incredibly difficult seem easy. You never, ever got the feeling that he was self-conscious in his poetry or pretentious in his aphorisms.”

Even as Kristofferson was battling the crowd at the Isle of Wight and wowing the audience at Monterey, he was enjoying one of the greatest songwriting streaks in country-music history. Earlier in 1970, his song “For The Good Times” had become a #1 country single for Ray Price and the Academy of Country Music’s Song of the Year. Then Kristofferson’s “Sunday Morning Coming Down” became a #1 country single for Johnny Cash and the Country Music Association’s Song of the Year.

Then Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through The Night” became a #1 country single for Sammi Smith and was later named the greatest country single of all time in the book Heartaches By The Number: Country Music’s 500 Greatest Singles by David Cantwell and Bill Friskics-Warren. That same year other Kristofferson songs became top-10 country hits for Waylon Jennings (“The Taker”), Jerry Lee Lewis (“Once More With Feeling”) and Bobby Bare (“Come Sundown”). That momentum continued into 1971 with top-40 country singles from Price, Bare, Lewis and Miller as well as a #13 R&B hit with Joe Simon’s version of “Help Me Make It Through the Night.”

But the big breakthrough was the version of “Me And Bobby McGee” recorded by Janis Joplin (Kristofferson’s lover for a brief while) just before she died on the day after the Big Sur show. When the single was released in 1971, it topped the pop charts for two weeks. Monument Records cleverly re-released Kristofferson under a new title, Me And Bobby McGee, and the poor-selling debut soon became a hit — as did its follow-up, The Silver Tongued Devil And I. The 23 songs on those two albums contain the vast majority of the songs that Kristofferson is remembered for today. It was a bounty that seemed to come out of nowhere, but it had been gestating ever since the songwriter moved to Nashville in 1965.

He came because he had grown up on the records of Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. He came because wanted to be a writer, and some of the best writing being done in 1965 was on country-flavored rock and country-flavored folk records.

“When I grew up, country music wasn’t popular with everybody,” he told this magazine in 2013. “I was going to high school out in California and they all called it shit. But largely because of the attention that Dylan brought to it by his respect for Johnny Cash and his friendship with Johnny and the fact that he came here to Nashville and recorded, all of the sudden the young people who like rock and roll realized there was something good going on here.”

He came because he had studied the poetry of William Blake as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University in England, and the most Blakean writer he could find in 1965 was Bob Dylan. He came because he really didn’t want to settle down in the academic job he’d been promised at West Point after three years in the U.S. Army. His first wife was unhappy with the decision, and his mother disowned him.

“I always felt that I was going to be some kind of writer,” Kristofferson told The Guardian in 2010. “I started writing a bunch of songs when I was over at Oxford.” A comic pause. “I didn’t know they were bad at the time … It cost me my first marriage, but I’m just grateful that I had the nerve to get out of the military.”

He got a job as a janitor at Columbia Records’ Nashville studio and was sweeping floors when Dylan recorded Blonde On Blonde there. He soon fell in with the crowd of songwriters that hung out at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge: Nelson, Miller, Bill Anderson, Hank Cochran. Tom T. Hall, Mickey Newbury, Tony Joe White, Billy Swan, Chris Gantry, John Hartford and Shel Silverstein. Several of them had penned hits for other singers, but Miller, with his #1 1964 hit, “Dang Me,” had proven that maybe they could sing their own songs.

“In general, we all just tried to knock each other out,” Kristofferson told the Nashville Scene in 2003. “You tried to find a way to impress the other writers, to get some attention for what you were doing. We felt like we were fighting for respect — from each other, from Music Row, from the world at large … We’d go out roaring for days at a time. Just partying, playing music and singing songs to each other. I loved it. It just intoxicated me. My excuse was that if I didn’t make it as a songwriter, I’d write a book about these people … We didn’t write these things because we wanted to have hits; we wrote them because we were trying to write great songs.”

Johnny Cash wasn’t part of that gang, but he appreciated their efforts. He took a shine to Kristofferson, and brought the youngster out on stage for his first public performance at the 1969 Newport Folk Festival. The army-trained Kristofferson once landed a helicopter in the couple’s backyard to give Cash a cassette of “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Cash maintained that he tossed the tape into the Cumberland River and told the songwriter to get off his property. Whatever happened that day, Cash did record the song, and it topped the country charts. He even defied the demands of television censors that he change the line, “On a Sunday morning sidewalk, I’m wishing, Lord, that I was stoned.”

“I first became aware of Kris,” says Rodney Crowell, “I think, during a televised country music award show when Johnny Cash’s version of ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down’ won Song of the Year. In a world where glitter and spangle was the predominant fashion, even for male artists, Kris looked like a Greenwich Village folkie. Though his hair was not yet long and his face was cleanly shaven, something about him evoked the image of the Poet.”

“When I was 16, I bought a Johnny Cash tape at a truck stop and listened to ‘Sunday Morning Coming Down,’” Hayes Carll remembers. “I had heard somewhere that Kris had written it and that he was a heavy hitter with an interesting backstory. That song was simultaneously so simple and profound, rough and poetic — it hit all the marks for what I loved in songwriting. A year later I heard ‘The Pilgrim: Chapter 33,’ and I had an out-of-body experience. The hairs on my arm were standing up and it shot an electric current through my spine. It was the coolest thing I had ever heard. I knew in that moment that I wanted to be a songwriter.”

The controversy over Cash singing “I was stoned,” however, was nothing compared to the uproar over Sammi Smith asking a man who’s clearly not her husband to “Help Me Make It Through The Night” on the #1 single of the same name. Suddenly we were no longer on the barstools, the front-porch rockers or the parlor cushions where so many country songs took place. Now we were in the bedroom and under the sheets, where country had never dared to go.

But once again, it wasn’t what Kristofferson had written about but rather how he wrote about it that made the crucial difference. “Take the ribbon from my hair,” Smith sang on the unforgettable first verse, “shake it loose and let it fall, laying softly upon my skin like the shadows on the wall.” Anyone who had ever been under the sheets with someone else had to be shocked by the familiarity of that description — too shocked to stop listening. Kristofferson captured farewell sex on “For The Good Times,” perfunctory sex on “Once More With Feeling” and fondly remembered sex on “Lovin’ Her Was Easier.”

“Kris was the first country music artist to intelligently articulate male vulnerability,” says Crowell. “I think it’s what made him a superstar. Women (and co-eds) loved it and so did the up-and-comers like me who dreamed of someday conjuring the kind of songs that would seduce co-eds — and, of course, women.”

“He said the things very few people would say but in a way that everyone wished they could,” adds Carll. “He made the complicated simple and the simple profound. He was a sensitive poet who could kick your ass but wasn’t afraid to be vulnerable or speak from the heart.”