Bruce Springsteen’s “Thunder Road” isn’t just a song you listen to—it’s one you watch—a sonic piece of cinema the budding songwriter produced, wrote and directed to screen in the theater of your imagination. Hell, it even takes its name from a 1958 Arthur Ripley crime drama Thunder Road—a drive-in vehicle for Robert Mitchum.

Videos by American Songwriter

Comparing Springsteen to pioneer filmmaker John Ford, Drive-By Truckers singer, songwriter and noted Springsteen fan and follower, i.e. “Tramp”—Patterson Hood— describes the song as Springsteen’s Stagecoach, in that it “announced his artistic arrival, that he is the ‘real deal’.”

“‘Thunder Road’ was like the opening action scene,” Hood tells American Songwriter, “setting the pace for what was to be an amazing adventure.”

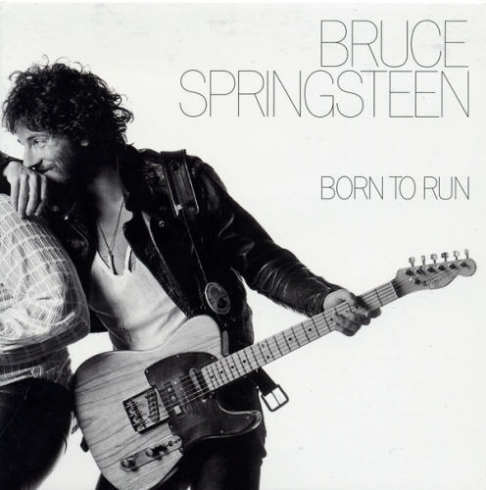

As a writer and rock and roll visionary, Springsteen would define himself through a sprawling 40-year career of working class anthems, sock-hop-ready rave-ups, emotionally devastating ballads, blood-on-sleeve rockers and soul-bearing love songs, resulting in a canon rich with insights into the human condition and the American experience—from the personal to the political. But Born To Run, his 1975 landmark third LP, is still very much his signature record. It freed the young songwriter of the “next-Dylan” claims critics hung as an albatross on his freshman and sophomore efforts, and established him as a singular entity—an outright master of rich, lyrical imagery, with a voice all his own. But the record isn’t a template for future successes like Darkness On The Edge Of Town, The River, or the blockbuster Born In The U.S.A. Instead, it was the beginning of what Springsteen would often call “a long conversation” with his audience.

It’s a conversation he could have started with his anthem-par-excellence “Born To Run”— opening the record with a battering ram, much like he did with “Badlands” on Darkness, or with Born In The U.S.A.’s title track. Springsteen takes a more inductive approach, opting for “Thunder Road”—a song crafted as a preamble, or as he called it, “an invitation” to a long-playing narrative about small-town kids dreaming of what lies beyond the horizon as the sun goes down on a sweaty summer night.

As the needle falls onto the LP’s A-side, simultaneous tension and release slowly focuses on the foreground. Swelling from the groove, the dreamy tickle of pianist Roy Bittan’s ivories chime in contrast to the yearning howl of a harmonica that sounds like the creak of a screen door slamming in slow motion.

As the tempo quickens to a bouncy lilt, the harmonica exits scene and we meet our nameless narrator and Mary, who, for the time being, suffices for his Juliet. She’s not a beauty but, hey, she’s all right. This is how Springsteen lets us know that, for his characters, it’s not love he’s getting at, but romance—romance and companionship, which has to beat being alone. Romance that makes a promised land of anywhere two lanes can take them, which has to be better than here, which is no place to grow old.

We can’t help but feel like voyeurs as Springsteen projects his vision of Mary dancing across a porch on the movie screen behind our eyelids, or as we watch the couple’s automotive chariot—their burned out Chevrolet, if you will—vanish like John Wayne into the sunset, or as we listen to The Boss make his guitar talk. And, with the knowledge that, regardless of how they prevail, our anti-heroes have already triumphed. Watching them take their destiny into their own hands is thrilling, because theirs is a town full of losers, and they’re pulling out to win. And by the time they do, we’re not watching, but riding along with them, cueing Springsteen and his famed E Street Band to drop into a deep-pocketed half-time and play us out with an ending-credits auditory epilogue for the ages.

And that’s just the first song on Born To Run.

Under the threat of losing his deal with Columbia, Springsteen’s future was riding on the success or failure of Born To Run, and he meticulously wrote, and re-wrote, and re-wrote its verses, and obsessively recorded, and re-recorded, and re-recorded every detail in aim of perfection—working his E Street soldiers like a general entrenched in a fight for life. But despite the lore of high stakes historically framing the album’s gestation, E Street bassist Garry Tallent paints a less dramatic picture. “It was very organic,” Tallent tells American Songwriter, “we were all kind of caught up in doing it, and we didn’t think too much about it …We just tried to make it sound right, and tried to make it feel right.”

“Thunder Road was one of those songs that, with the pictures that the words gave you—it was just real immediate, and we said, ‘Yeah, okay! This is a great song, let’s work on this. Let’s make this happen,” says Tallent.

It did happen. And it was a hit, helping to catapult the young singer to the covers of Time and Newsweek magazines simultaneously, and taking its place as one of the most essential, definitive and loved entries in the Springsteen songbook, as well as a perennial staple of the singer’s legendarily live shows.

It even had a sequel—“The Promise.” That didn’t happen, as the song, originally intended for Darkness, was scrapped, eventually finding its way to non-bootleg status when it was re-recorded and released as part of 1999’s 18 Tracks odds and ends release, in addition to providing the namesake for 2010’s Darkness reissue package.