Amanda Shires

Videos by American Songwriter

Leonard was a seeker, a searcher and a companion to all of us that have been long-time wanderers and long-time sufferers. His songs are the kind that will last forever; they’re the kind that have been stitched to our world with elvish thread. He had a superhuman ability to translate the human condition into words and song. He explained our feelings to us and for us. He encouraged us to be compassionate and to open our eyes to each other. He went into the trenches of darkness, met loneliness, studied love, meditated and fought, sacrificing himself along the way. He made our flaws and scars feel earned and lovely. He coaxed us like hungry birds to the truths that he kept finding underneath his hat. I know that he will be forever unmatched, bringing grace to music and beauty to the parts of ourselves that we have known to be ugly.

Since his passing I have been thinking a lot about his Isle of Wight performance. That night in 1970 Leonard reminded us that we could renew ourselves at any moment that we choose to, in any place of our choosing. Because this past year has been a year of losing and loss, and because many of us are hurting under a tarnishing golden rule, let’s try and go forward in service to the higher power and in service to one another. Let’s remember that we can renew ourselves. Let’s make an effort and let’s not be lost.

Aaron Lee Tasjan

Dark, exhilarating and angelic, the music of Leonard Cohen now remains an everlasting sanctuary to all who would listen. Mr. Cohen left us November 7th having just released one of his most brilliant albums yet, titled, You Want It Darker, while declaring in a recent interview with The New Yorker he was “… ready to die.” Despite his prophetic words, it seemed sudden when we lost one of the true American masters of song and poetry. He writes brilliant lines that say so much with such economy. In “Love Is A Fire,” he says of love, “It’s the world’s excuse for being ugly.” Cohen always writes with a frozen rope right through the heart of the song. You can hang anything off it and it still rings true. These songs are built to last and they won’t ever fail you. In a world where it seems hard to know what to believe, it’s of great comfort to have songs such as these to believe in.

Robert Ellis

His words and music have the ability to pull me out of wherever my head is at and bring me into the present … really noticing things, feeling everything deeply. When I’ve been down he has given me humor. When I’ve been in love he’s given me a language for the things I feel but don’t know how to say to someone. I’m deeply saddened that we won’t have him here to help us make sense of the world and I’m forever grateful.

Henry Wagons

I’m so glad Leonard Cohen was here. At once gentle and powerful. His poise and mesmerizing delivery unmatched. His wicked humor. I loved his songs, all the way through, every word weighted and balanced. I’m left forever hypnotized. Rest In Peace.

Ruby Boots

I was singing my favorite Leonard Cohen song, “Chelsea Hotel #2,” while soundchecking for a show when a friend delivered the news of his passing. His words have influenced my music and have helped and inspired me to break open parts of myself lyrically that perhaps would have remained untapped. Thank you, LC.

James Wilson of Sons of Bill

Leonard Cohen’s songs are often described as timeless. While I wouldn’t disagree, “timeless” here can’t simply be another overused journalistic synonym for “good.” With Cohen the word means something else. His songs have an abstracted quality that is almost pathological: Ageless. Placeless. They are like little hymns with no church, stories riddled with minute details and particularities that still somehow always manage to be more bewildering than grounding. I don’t know anyone that loves them that wouldn’t describe themselves as haunted by them.

It could be that Cohen’s songs are timeless because they are essentially tragic, in the classical sense of the term. They give us a picture of man, little vignettes of Cohen himself, blindly stumbling like all of us between his fate and his responsibilities, his drive for freedom and his incontrovertible circumstance, haunted by an incessant dream of perfection in a world that always seems to come up short. For all of the poetic romanticization of a life spent “paying rent in the Tower of Song,” does Cohen himself not clue his listener in to what this actually means? The basic and fundamental fear of simply being human? It’s a question Cohen tirelessly drove at his entire career, and his life’s work is a beautiful and tragic record of what it costs.

Matthew Ryan

Almost exactly a year ago I sat on a park bench across from Leonard Cohen’s modest Montreal home. It was very much an accident that I ended up there. It was October, 2015. It was cool and evening had crept into all the corners of the neighborhood. People and cars glided by; I was soon to play a show just up the street. A friend knew of my love of Leonard’s work, so they took me there. We sat quietly. I didn’t take a picture — dignity insists you respond in kind. I grew up with Cohen’s voice in my childhood house. He’s been a great companion through every mile marker in my life so far. And in the harder parts, he taught me how to breathe in a bunker. He taught me that grace and poetry are the muscles that matter; they visit us after the battles, inside and out. I’m going to miss him.

But I’m so grateful to have shared a gap in time with him. What a privilege to have experienced so much of what he created while it was happening. The world he observed and communicated, both inside and out, feels like the world I’ve been trying to come to terms with … fellow listeners of Leonard’s are probably the only people that will fully understand what I mean by that. But believe me, you’re all invited, you always were.

Maybe it’s not fair to Leonard Cohen to draw this thread that I’m drawing. His work is beyond compare; his art is among the humblest of high art. He traveled through the dark to find light and became something that has become so rare. He became a kind of true statesmen for the human heart. No goofiness, no salesmanship, no need beyond the need. Nothing but great melodies, a “golden voice,” and immeasurable words — comfort, humor, sensuality and armor. And he shared them with those of us that welcomed it, needed it and thirsted for the illumination of the entirety of our humanity.

On the early morning of November 9th an idiot walked into the highest office of our land; on November 10th, we were told that a monument to dignity walked out. And if all I’ve learned from Cohen’s work is true, there’s a lesson here that simultaneously means everything and nothing. But know this, the future now will be what we allow it to be. And it’s up to us to see the beauty that’s always right there, right in front of us, invisible but absolutely exhilarating, alive and waiting.

Thank you, Leonard Cohen.

Kate Tucker

I’m honored, humbled, and afraid to write about Leonard Cohen. I struggle to find the right words, as he often did so patiently on our behalf, line-by-line, song-by-song. His work was an exercise in intention. Listening to it demands a certain silence, an admission of love, a commitment to life beyond boogie street. You Want It Darker came like a poultice for suffering, in a year that has been darker than any I can remember. Upon news of his death, my sister and I stopped the film we were watching, turned out the lights, lit candles and cried. We cried for Marianne, for King David, for the now defunct Chelsea Hotel, for Suzanne with her tea and oranges, and for our mother, who also died this year. We cried with our friend in the tower of song who teaches us how to live on.

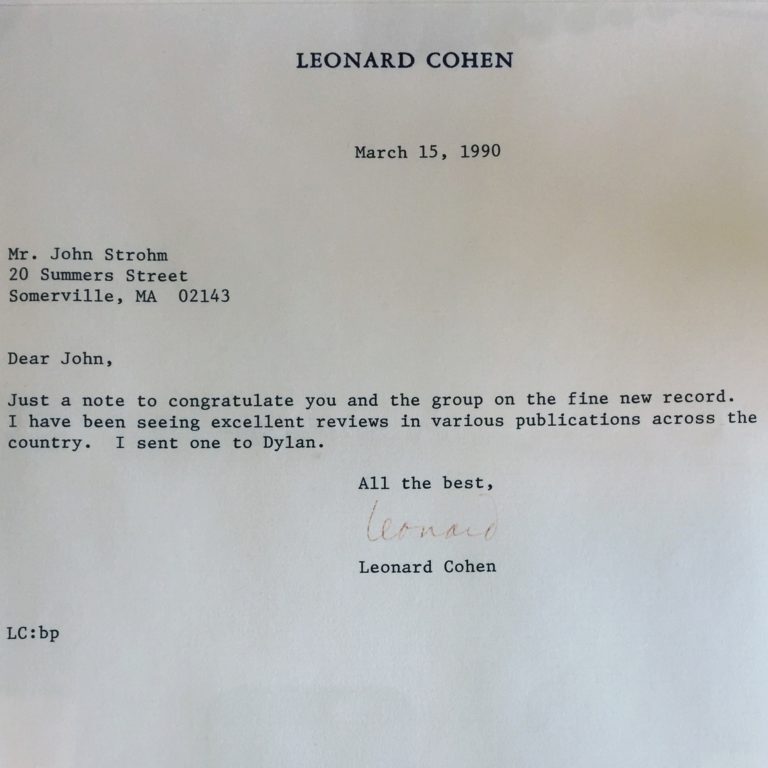

John Strohm of Blake Babies, The Lemonheads

Sometimes the songs that haunt me the most are the ones I heard around the house as a young child. Although nobody else in my family plays music, we’re all huge music fans – especially my English professor father. Before I could walk I spent a lot of time looking through his album collection as sounds of Dylan, Billie Holiday, The Stones, The Band, Joni Mitchell, and countless other greats serenaded from the walnut-cased Pioneer speakers. I loved some of it (The Beatles naturally), hated some (country blues and bluegrass), as most of it went unnoticed.

One album that really bothered me was Songs Of Leonard Cohen. The eerie photo on the cover (looking more or less like one of my dad’s professorial colleagues), the bizarre Anima Sola image on the back cover … all just gave me the creeps. I felt both drawn to and repelled by the eerie strains and ghostly voices of Suzanne, which he played constantly. It seemed mysterious and unsettling.

In my late teenage years I rediscovered Songs Of Leonard Cohen, along with the rest of his catalogue. It still seemed eerie, but in a way that really drew me in. I listened to his records obsessively for years, learned to play all his songs, read his novels and books of poetry. Along with study of Lou Reed and Hank Williams, it’s really how I taught myself to write songs. I still remember how to play and sing at least 20 of his songs, and that’s half as many as I could play back in 1988.

I mention 1988 because that’s the year he released his masterpiece, I’m Your Man, and also it’s the year my dad started seeing a woman, a history professor, who had previously dated and remained friendly with Leonard. Occasionally Leonard would leave messages on my father’s answering machine for his friend, and dad would save them for me to hear when I visited. He would make the most mundane things sound incredibly profound and poetic. That voice …

In 1990 my band, Blake Babies, released our first album on Mammoth Records, an independent label based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. We were all in our early 20s, and it was a very exciting time. After several years of struggle, suddenly we were touring the nation, getting lots of college radio airplay, and getting reviewed in Rolling Stone. One day a letter arrived in my mailbox from Leonard, congratulating me on our release. He sent one to Bob Dylan, he said. I can’t explain how thrilling it was for me to receive this letter. I immediately had it framed and it’s on my office wall today. I wrote him back, and I’m sure I’d be embarrassed to see what I said. I cherish the letter, and I think it really shows what a generous man he was. He knew how much I loved his music, and he knew how much it would mean to a kid like me.