Videos by American Songwriter

Every year the Grammys choose five songs to nominate in the main songwriter’s category of the night, Song of the Year. Many of the songs which have been awarded with this honor over the years became modern standards, including “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Moon River,” “That’s What Friends Are For,” and “Wind Beneath My Wings.” Others stand as powerful reflections of a particular moment in our cultural history, such as “We Are The World,” and more recently, “Rehab” by the late Amy Winehouse, and “Royals” by Lorde.

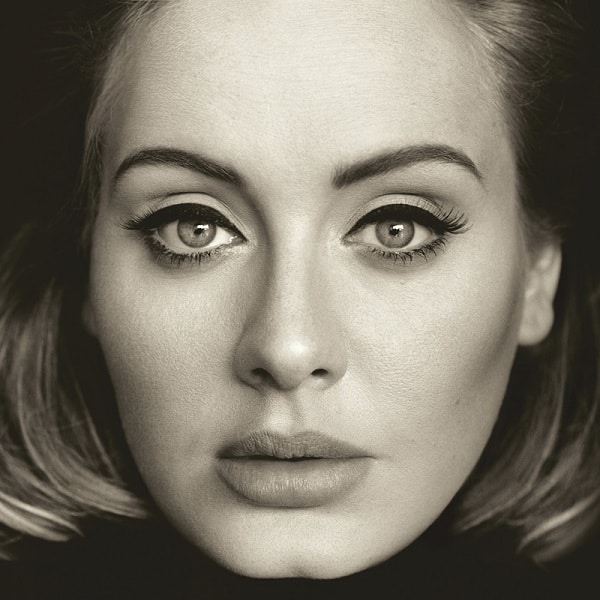

The winner for Song of the Year this time around was “Hello,” by Adele and Greg Kurstin (about which she spoke at length in yesterday’s Backstage Report from the Grammys.) “Hello,” remarkably, became somewhat of an overnight standard, one of the most quickly beloved songs in modern history.

Here’s a quick look at the five songs nominated this year.

“Formation,” Khalif Brown, Asheton Hogan, Beyoncé Knowles & Michael L. Williams II, songwriters (Beyoncé)

Lest anyone assume that today’s songs don’t pack a powerful cultural punch, look no further than “Formation.” Crystallizing the ever-intensifying racial divisions in America which led to the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement, Beyonce and her co-writers (Khalif Brown, Asheton Hogan, and Michael L. Williams II) crafted a compellingly authentic statement of black pride and preservation. Accompanied by a video which generated over seven million views in one day, the song did what great art often does: it both empowered and outraged people. Many criticized it as anti-police, about which Beyonce stated to Elle: “I think the most powerful art is usually misunderstood… anyone who perceives my message as anti-police is completely mistaken… I am against police brutality and injustice… If celebrating my roots and culture during Black History Month made anyone uncomfortable, those feelings were there long before a video and long before me. I’m proud of what we created and I’m proud to be a part of a conversation that is pushing things forward in a positive way.”

Despite the controversy, she remained resolute in her conviction that the song effected progress. “I hope I can create art that helps people heal,” she said. “Art that makes people feel proud of their struggle. Everyone experiences pain, but sometimes you need to be uncomfortable to transform. Pain is not pretty, but I wasn’t able to hold my daughter in my arms until I experienced the pain of childbirth!”

“Hello,” Adele Adkins & Greg Kurstin, songwriters (Adele)

Both haunting and triumphant, “Hello” is pure Adele, both remarkably powerful and vulnerable at once. Though she’s happy now and long past the “rubbish romance” which inspired so many of her early songs, this time around she channeled ghosts of the past to color these new songs. As her collaborator Greg Kurstin explained, “We were happy at the time, but I tend to go for moody chords, and Adele’s voice invokes so much emotion.” That emotion, attached to the soaring “Hello from the outside” refrain, was so chilling that both songwriters recognized it instantly: “I started playing piano chords,” he said, “and Adele sang different ideas until we landed on what became the verse. I improvised while she thought of ideas on the spot.” About the feel of merged loss and triumph, he said, “I was trying to find a balance, and with the verse production being what it was, the chorus ended up quite uplifting.”

That strident sound of Adele belting out the dark but exultant chorus as only she can, in full voice, was there from the start, but with a slight key alteration. “Adele sang the chorus out while we wrote it, as it is on the record,” he said. “It was originally in F# minor but we took it down to F minor. I like the darker sound that it became after doing that.” Asked if “hello from the other side” refers to the other side of life, Kurstin said, “That was all Adele. I’ll have to ask her!”

“Love Yourself,” Justin Bieber, Benjamin Levin & Ed Sheeran, songwriters (Justin Bieber)

Hinged on a self-referential line that evokes the infamous “You probably think this song is about you” lyric from “You’re So Vain,” here the singer distances himself in the song from the song itself: “I didn’t wanna write a song/’Cause I didn’t want anyone thinking I still care …” Sparsely-produced and acoustic, it was co-written with Ed Sheeran and Benjamin Levin, and enhanced by Sheeran’s organically fluid phrasing. Although the title implies self-affirmation, it’s actually a condemnation of those so consumed with self-love that they’re incapable of loving another. To Australia’s Sunrise TV show in 2015, Bieber announced that Ed Sheeran had written a song for him.

To Capital FM, he said, “I think [Sheeran] is one of the most talented writers in the game right now, so to have his input and stories and our stories and match them up together, is amazing …” About the arrangement, he said, “It’s just me and a guitar. Basically that’s how I started, playing on the street with a guitar.”

Calling into On Air With Ryan Seacrest, Bieber expounded on the song’s subject: “It’s definitely about someone in my past, someone who I don’t want to put on blast. It’s cool because so many people can resonate with that, because how many women do we bring back that mom doesn’t really necessarily like?” For his part, Sheeran performed the song once live at a UK benefit concert. “I’ll probably never play it again,” he said, “but I just want to play it once.”

“7 Years,” Lukas Forchhammer, Stefan Forrest, Morten Pilegaard & Morten Ristorp, songwriters (Lukas Graham)

“7 Years” is the rare song that spans decades in the singer’s life, reflecting backwards to the past and forward to the still unrealized future. It started when bandmate Morten Ristorp played a repeating riff on a “cheapo keyboard,” inspiring Lukas to run to the mic to sing. The first words that emerged were, “When I was seven years old.” Recognizing he had something, he started writing down the words: “I kept writing more about ages 7, 11, 20,” he said. “Then we passed the age we were and went on to 30 and 60. It took three and a half hours to write.” To refine the lyric, he turned to Stefan Forrest for input. “I was jamming on the song,” he said, “and Stefano was egging me on.

He is very good at emphasizing when I could write a line better. When we write together, songs become more complete.” Sound-designer Morten Pilegaard, who Lukas refers to as “a good finisher,” tweaked the sonics. Unlike many artists, who rarely share writer’s credit, Lukas includes everyone: “It’s very much a group effort. We all contribute our special touch to the music and give credit to anyone who can enhance the music. Sharing is caring.” As for his proclivity with profuse rhyming, he said, “I started writing rap music when I was in my teens. So when I improvise melodies, the rap rhymes come easily.” Admittedly stunned by his multiple nominations, he said hearing the news “was unfathomable. Only eleven people in Danish history have been nominated for a Grammy. And now we’re nominated for three.”

“I Took A Pill In Ibiza,” Mike Posner, songwriter (Mike Posner)

It started when a friend challenged him to write something true. “I told him I made up my songs,” said Mike Posner, “and he said, `Why don’t you just tell the truth?’ I didn’t have an answer. I got on an airplane, and on the flight I wrote the song. It was my slow answer to that question, my first attempt at telling the truth in a song.” On the plane he wrote the top line melody and the words, casing out the chords later.

“I explicitly do not try to make songs relatable,” he said. “I would rather write something that is real to me. Now, no one who is listening to the song has taken a pill in Ibiza in front of Avicii. So my goal is to never write someone else’s story. I’m doing what’s real to me. I’ve come to understand that the more specific a song is, the more universal it becomes.” Though titled for the first line, the song encompasses several stories, as he said: “One is of me in my hometown. Fans asked me how to make it and I told them you don’t want to be high like me.” Unlike most modern songs, which are recorded immediately, Posner performed it on the road for more than a year before recording it, shaping it gradually. “I knew it was a special one,” he said. “Playing it live was great. By the end of the song, they would be singing the chorus with me.”