There aren’t many country artists who could turn a song by an iconic punk band into a duet with a bluegrass icon, but Dwight Yoakam has never let convention stand in the way of his muse. Whether performing the Clash’s “Train In Vain” with Ralph Stanley, duetting with Buck Owens on “Streets Of Bakersfield” (Yoakam’s first No. 1), adding vocal filigrees alongside Flaco Jiménez’s accordion on Warren Zevon’s “Carmelita” or crafting timeless originals like “A Thousand Miles From Nowhere” (from 1993’s now-classic This Time), his career has always defied both genre constrictions and music-biz norms. On his latest album, Swimmin’ Pools, Movie Stars …, Yoakam even gives “Purple Rain” a bluegrass transformation, reaffirming that it’s possible to celebrate tradition while stretching boundaries.

Videos by American Songwriter

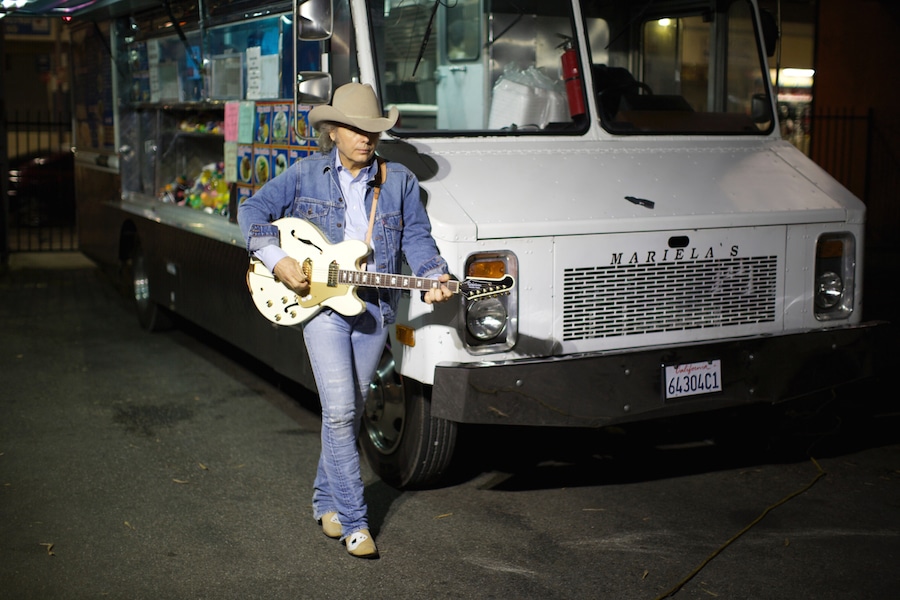

From the start, Yoakam’s Bakersfield twang and hip-swiveling swagger straddled what Vanity Fair called “the divide between rock’s lust and country’s lament.” Considered a co-founder of L.A.’s cowpunk scene, the self-taught guitarist fused honky-tonk, rockabilly, punk and bluegrass into a sound described as “Bill Monroe meets the Ramones.” He scored his first hits with 1986’s Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc., an expansion of his self-financed, indie-label debut EP. When MTV aired his “Honky Tonk Man” video as its first-ever country clip, pronouncing it cool for rockers to dig this “honky-tonk hillbilly,” they helped boost the lanky cat in the cowboy hat, skin-tight Levi’s and Cuban-heeled boots to superstardom. (In the process, they also helped refocus some attention on traditional country after the 1980 film Urban Cowboy put a slicked-up sheen on the genre.) Three decades and nearly 30 albums later (including compilations), just about every one placed within the top 60 on Billboard magazine’s Top Country Albums chart, except for Reprise, Please, Baby, a four-disc box set of his work on that label. Seventeen reached the top 10, a remarkable feat. Of Yoakam’s 18 studio albums, only three ranked below No. 11. His first three releases went to No. 1; his latest three (3 Pears, Second Hand Heart and Swimmin’ Pools …) reached 3, 2 and 6, respectively — and Swimmin’ Pools topped the Bluegrass chart. He’s sold over 25 million discs while earning 21 Grammy nominations (and two wins), dozens of other accolades, and bona fide legend status.

Born in Pikesville, Kentucky, and raised in Columbus, Ohio, Yoakam began performing in high school, singing in a rockabilly band, acting in student productions and even drumming in the marching band (after ditching football). After a year at Ohio State University, he went to Nashville to audition for a summer gig at Opryland Park. They offered him an alternate spot, so he headed to California instead. That brought him closer to Owens and Merle Haggard, and to a flourishing country- and roots-rock scene. He never looked back.

Yoakam continued to act as well — in films such as Sling Blade, The Newton Boys and Panic Room and TV shows including Goliath and Under the Dome. He also co-wrote, directed and scored the film South of Heaven, West of Hell, and directed several of his music videos.

Discussing his career, he sounds more like a cultural anthropologist than a singer-songwriter. Remarkably well versed in American history, geography, sociology and even behavioral evolution, he recommends books, cites studies and offers several intriguing insights. Often interrupting himself to add background or further detail, he speaks in marvelous phrase mazes that somehow synchronize into sentences — but could just as easily become perfect lyrics.

How old were you when you moved from Kentucky to Ohio?

I was about two. But it’s like saying you moved from Philly to Jersey. It’s 90 miles from Columbus to Ashland, Kentucky. It was a common migratory [path]. The coal mines in that region were slowly closing. The house I lived in when I was first born, my grandparents had purchased from an old coal company. When those mines would close, they sold off the housing that they had built up in the hollers.

There was this cultural shift occurring in the late ’50s when mines were closing. And my father was a career soldier; he’d been a sergeant in the Army. Because he couldn’t move my mother and myself where he was stationed, in Korea, he resigned, and we moved there. It shaped me, not unlike John Prine. I look to John as a benchmark. I discovered him in the ’70s. His first album had the song “Paradise,” about his family migrating to Chicago from western Kentucky. I began to realize that the banal aspects of someone’s life, like mine, that I had always viewed as — it was almost an epiphanous moment when I was a kid riding Route 23 and thought, “There’s something about this I’m supposed to [absorb].”

The deeper we got into Kentucky, I would begin to hear things on the car radio that were completely colloquial, steeped in mountain music. It was just there, in the air. We called it goin’ home. We’d leave Columbus and make that drive on a Friday night; I used to say it was like being a taillight baby. You’d see this line of cars with Ohio and Michigan license plates. I wrote the song “Readin’, Rightin’, Rt. 23” about the families that migrated out of that region being the brunt of a joke in Ohio.

I’m from Pittsburgh, so I know the lay of that land.

It’s all Appalachia. From Pittsburgh, you drive 40 miles and you’re into West Virginia and deep Appalachia. It’s very much a large, regional, symbiotic relationship, the Ohio Valley. There’s a great book called The United States Of Appalachia. The author deals with, sociologically, the impact of the Appalachian Mountains, from New York state, where they begin, to the Alleghenies, all the way down to easternmost Mississippi, from pre-Revolutionary War … I realized as an adult, having moved away, it gave me a perspective that was unique. And my collision with Prine’s articulation of his family’s regional cultural experiences and how they shaped him, and how he expressed that in song, profoundly impacted me. I realized I needed to articulate those things about my own family that impacted me so dramatically.

When did you start writing songs?

The first thing I attempted was “How Far Is Heaven.” The Vietnam War was going on in the living room every night, starting probably when I was 8 … My father was no longer in the military, but I heard about it every night at the dinner table, because he spent half a career as a staff sergeant. So I wrote about it from a child’s perspective of losing a father who went to war and never came back. It was later, in high school, that I began in earnest.

You’ve covered rock and pop from Elvis and the Everlys to the Clash and Queen. In L.A. you found kindred spirits in John Doe and the Alvin brothers, and opened for X, the Blasters, the Knitters, Rank & File and Los Lobos. Yet they were cowpunk roots-rockers and you scored big in country. What was the distinguishing factor?

We had such an affinity. Pete Anderson, my lead guitar player and the producer on all of my albums, like, for 18 albums, was from Detroit. His father had moved from western Kentucky to work in the factories. Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers, makes a reference about Appalachian kids, about Harlan County in Kentucky, where they couldn’t keep a circuit judge for many years because of the threats. The feuds would spill over into the courtroom. That culture remains in the DNA. [Gladwell cited] a University of Michigan study about cultural behavior and the instincts of people who come from hardscrabble herding cultures versus agrarian cultures. When they came from someplace where you could not let the slightest affront go unanswered because someone might be testing your perimeters to circle back and steal your livestock, as opposed to an agrarian culture where there’s more need to engage in community reliance … these are cultures that individualism is borne out of. And Pete and I realized [we] had that with each other. There was this stubbornness … I wouldn’t do covers of songs on commercial country radio in 1980; I was doing Bill Monroe. To me, that was country music. I wanted to play what I grew up listening to.

We’d start every show with [Monroe’s] “Can’t You Hear Me Calling,” and go right into “Rocky Road Blues.” I did George Jones’ “The Grand Tour.” I was doing what was part of my DNA. And it was freeing. Country-rock was one of the things that drew me to the West Coast. I knew there was an opportunity for me to speak to my own generation, musically, in a way I hadn’t been able to in school. There’s a great legacy of country music in southern California … because of the Dust Bowl-migration bringing out all these folks from the Plains states. World War II drew an entire generation of young men from Appalachia to the aircraft factories and military bases on the West Coast. It ended up having a profound impact on California culture. That’s why Buck Owens and Merle Haggard became two of the great country music stars in their generations in California.

I knew what had emotional connection for me. And it had that kind of emotional connection for the young rock audience that had been, a lot of them, former punk musicians. I’m from the generation of musicians that gave the world punk rock. The first time I heard my record play, on KXLU radio, the Loyola Marymount college station, I was listening to Stella Stray Pop, [that] was the title of the show, and she played me between the Dead Kennedys and the Butthole Surfers — a hardcore honky-tonk song that has Merle Haggard influence in it, “It Won’t Hurt.” That was the moment. It’s a byproduct of the culture in southern California.

You might have been a maverick musically, but it seems like you molded audiences to what you were doing, instead of vice-versa.

Here’s the thing: record companies and radio and television, commercial ventures, needed to give categoric qualification. Musicians don’t think in terms of categories. They just think in terms of what interests them musically. We tend to sing songs that transcend boundaries of genre. I was listening to the Clash on the radio; I listened to all kinds of radio. In the ’60s, you could listen to Top 40 radio, and truly hear, unlimited by genre, musical expressions. There was an eclectic mix that truly was just the top songs in the country at that time.

SIDEBAR: DWIGHT YOAKAM’S CLASSIC VIDEOS

I always believed audiences were predisposed to like a variety of music. When we started the show with “Hear Me Calling,” it wasn’t polite. The audiences were willing [to listen] because country music was a rebellious music. Bluegrass was an obstinate form of expression, musically, to the sophisticated forms coming out of the urbane parts of society. They looked at bluegrass musicians as cultural hellions and punks. So rock audiences had an emotional affinity.

[Bluegrass has] always been part of me. That’s why Ralph Stanley invited me to be a part of the Saturday Night & Sunday Morning double LP he put out in the early ’90s. After we finished those sessions, he said [imitating Stanley]: “Dwight, I believe you might be a bluegrass singer.” I said, “I probably am. In disguise.”

You’ve now been embraced by the Americana community, which took longer than it should have, considering your genre-crossing history.

Well, they gave me that Artist of the Year award a couple of years ago [2013]. Because of the commercial country radio success I had, it took a while for everybody to get back to understanding that the cross-genre nature of what I was doing was what led to the commercial radio success. Because I would come and go from country radio even at the height of that part of my career. I would have years where I wouldn’t be on the radio … there was an ebb and flow.

By the time I came along in the late ’80s through the ’90s, things had become so narrow-cast, it was tougher [to cross over]. Even breaking out on MTV, once I had commercial country hits, they stopped playing me. You were relegated to only having your video on CMT or TNN. Willie did it with the outlaw movement in the middle ’70s when he and Waylon broke with that platinum album [Wanted! The Outlaws]. I came from that moment. I remember that Red Headed Stranger album; what that meant to me as a songwriter was, “Hey, I can do exactly this, the things that are from my cultural legacy, and my family’s culture and the culture I was born into, and have it still remain pertinent for a contemporary audience of my generation.” I thought, “The odds and the gods will smile on that.” And fortunately, they did.

Who are some younger songwriters you respect? And can you talk about your songwriting process?

I admire Brandy Clark. … She’s a songwriter who takes from a variety of influences and genres and expresses it in a singular way. And recently, I wrote with Chris Stapleton. Chris was born in Paintsville, Kentucky, 40 or 50 miles north of where I was born. It’s Johnson County, where Loretta Lynn comes from, so there’s this whole eastern Kentucky connection. My first thing I co-wrote was with Roger Miller, which was an auspicious beginning. I hadn’t co-written much because, as Roger said to me when we first got together, he felt it was something that was akin to a cat having her kittens; you crawled off underneath the house and did [it] by yourself [laughs]. And I understand that, so I said to Chris when we started, “I don’t know how you approach writing, but I’m always trying to listen over my shoulder to see if I can catch sight of a wisp of smoke.” ‘Cause that’s what songs are to me — wisps of smoke that I’m trying to capture, and trap under a glass dome and watch it float around. If you don’t, it’ll dissipate. You’ll miss it. Songwriting’s always been a bit magical to me, and a bit mysterious, which I like. It keeps me infatuated, thinking, “How will I get to there from this thought?”

Even when you’re collaborating, the good songwriters are still enjoying the process of letting the other collaborative partner be themselves. To bring to you what you wouldn’t bring on your own, and conversely, hopefully.

What do you see as your legacy? Or what do you hope it is?

I don’t really dwell on that. What I would hope is that my music brought joy, and because it can be heard beyond my own mortal existence, that it would continue to bring joy. And some sense of connection to the rest of us, or connection through it to feeling not so alone. Having some affinity to somebody else in the world. I think that’s why we’re drawn to songs. We feel a commonality, and possibly a sense of understanding.