Robbie Robertson built much of his reputation as a songwriter detailing the history of the American South. Only towards the end of his time with The Band did he write of historical events that took place in his native Canada. “Acadian Driftwood”, released in 1975, manages to make a connection between Canada and the South, particularly New Orleans. And it stands as one of the most moving songs in The Band’s catalog.

Videos by American Songwriter

Robertson’s Journey

Robbie Robertson began touring America with Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks in the early 60s when he was still a teenager. A fan of roots music, he marveled at the connection between the land and the songs at practically every stop on that journey. That was especially true when The Hawks rolled through the South.

When he became the chief songwriter for The Band a few years later, he remembered those formative experiences. His interest in the South was also fueled by his friendship with Levon Helm. Helm, the lone American member of The Band, hailed from Arkansas.

From all that sprung brilliant Band songs such as “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)”. Eventually, Robertson turned his songwriting gaze back to his home country, in particular, the tragic story of the Acadians, French settlers who had been displaced by the British in the 18th century.

Many of these folks eventually made their way down to Louisiana. Natives of France already made up much of what was, at the time, a small population. So many Acadians eventually found their way to New Orleans that the Cajuns (the name derived from “Acadians”) would soon become a fixture in the area.

Exploring the Lyrics of “Acadian Driftwood”

Don’t go looking to “Acadian Driftwood” for exact historical accuracy. The main issue is that Robertson makes it sound like the Acadians were forced out as a result of the French and Indian War, which pitted France against Great Britain on North American soil. In actuality, they began to resettle before that war even began.

But what’s important is that Robertson, with help from brilliant vocal performances from Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Levon Helm, gets to the emotional heart of the tale. He tells it from the perspective of someone already living in New Orleans, recounting the injustice of it all. “Loved ones forsaken, they didn’t give a damn,” Helm sings. “Try to raise a family, end up an enemy.”

Robertson explains that some of the Acadians managed to resist the move (and British forces) through pure resilience. “They never parted, they’re just built that way,” Manuel moans. The narrator traces the different paths his people took, some battling the elements in Canada, others sweltering in Louisiana.

In the final verse, the sense of displacement hits heavy. “This isn’t my turn, this ain’t my season,” Manuel sings. “Set my compass North, I got winter in my blood,” Helm seconds. The chorus brings those masterful voices together to mourn the fate of this proud people: “What a way to ride, oh what a way to go.”

To round it all off, the final section features Manuel and Danko (the two Canadians) singing in the Acadian dialect. Roughly translated, the words speak of homesickness and the wonders of Acadia. With that, the majestic “Acadian Driftwood”, one of the final and finest examples of The Band turning history into musical magic, fades to a close.

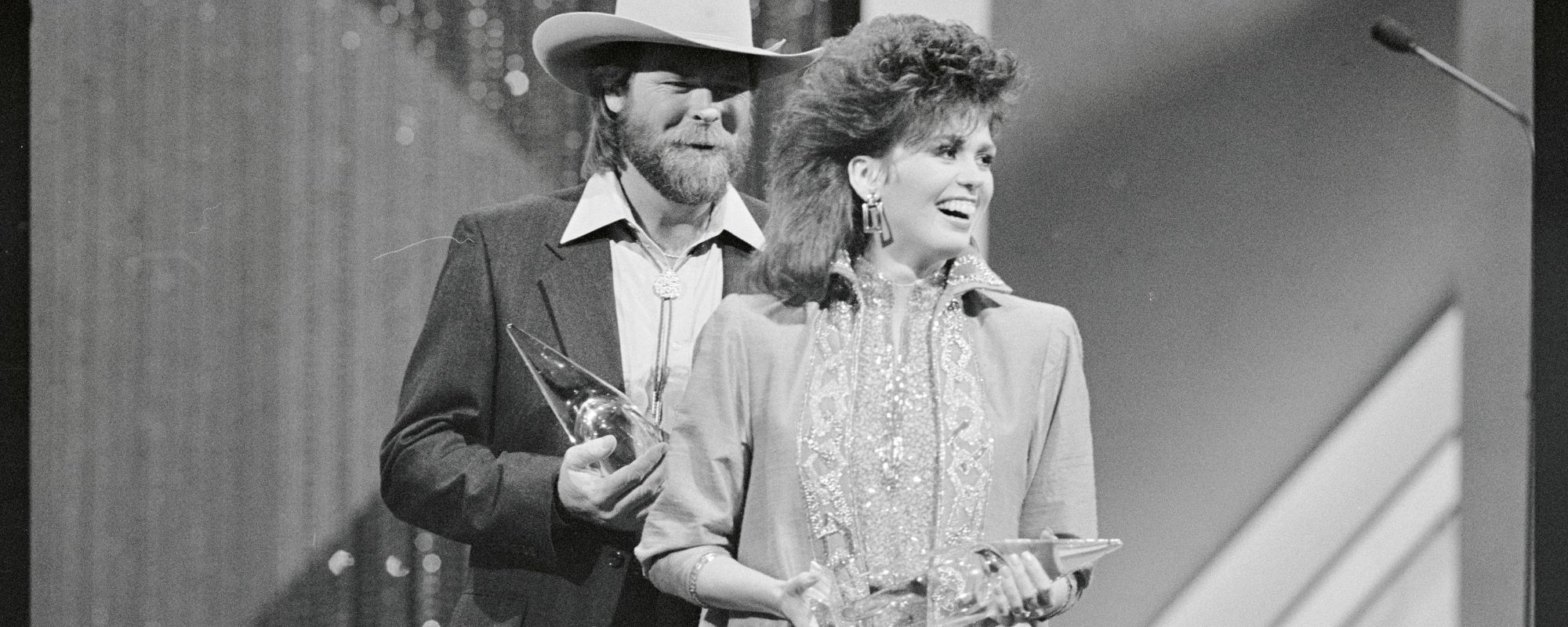

Photo by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.