It’s difficult to narrow down the foundational guitar riffs of rock music. Like everything, music evolves while songwriters borrow, steal, and recycle what’s come before. The most iconic riffs are really just interpretations and adaptations of earlier songs. All musicians, even the greats, stand on the shoulders of giants. So, acknowledging that this list will be far from complete, let’s instead think of it as a snapshot. Three (of many) iconic guitar riffs from the 1950s that forever changed rock history.

Videos by American Songwriter

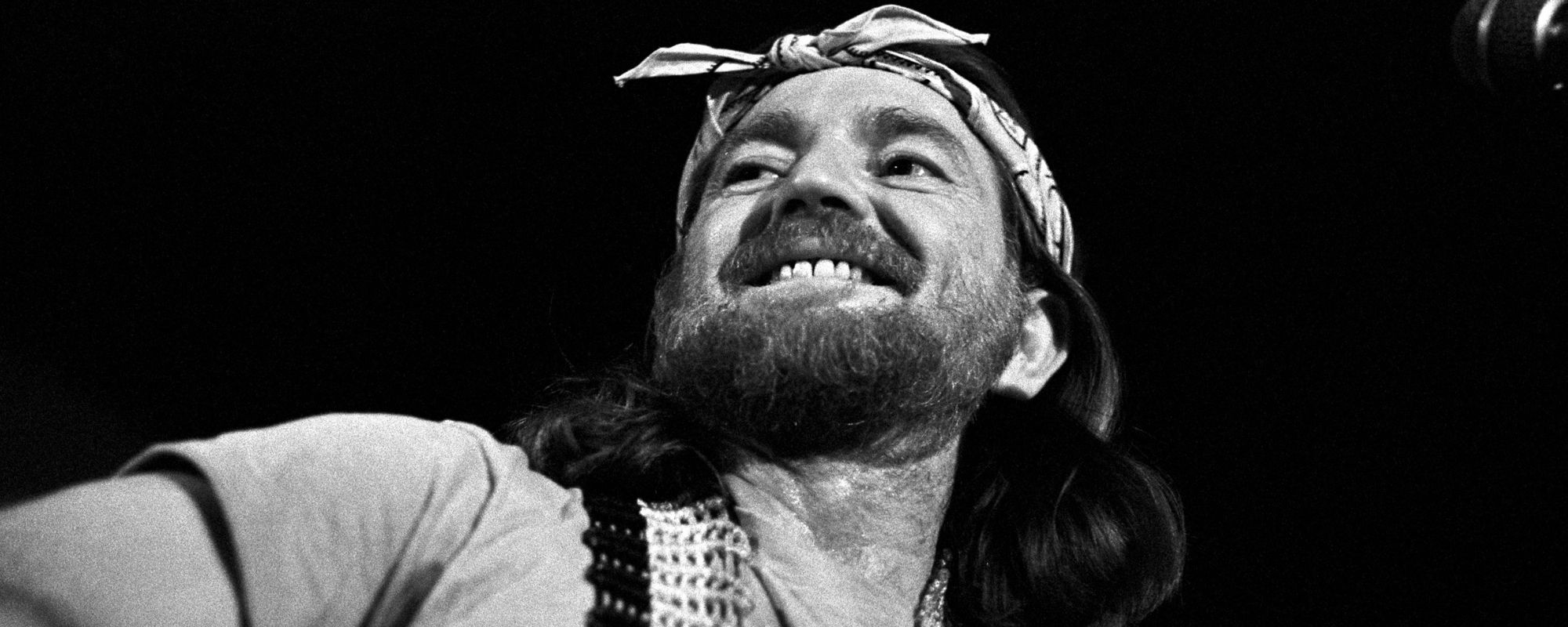

“Rumble” by Link Wray & His Wray Men

One wouldn’t think an instrumental piece of music would run the risk of being banned. However, Link Wray’s groundbreaking “Rumble” did just that. In 1958, radio programmers thought the title promoted gang violence. They viewed the track’s harsh mix, unheard of at the time, as provocative and certain to promote social unrest. Wray’s use of distortion and tremolo effects has since become standard in rock and roll. A brawling classic with a blueprint for the genre’s future evolution from garage rock to punk. Wray’s group wouldn’t be the last to ignite a heaving overreaction to a song. This, too, became a regular feature of rock music.

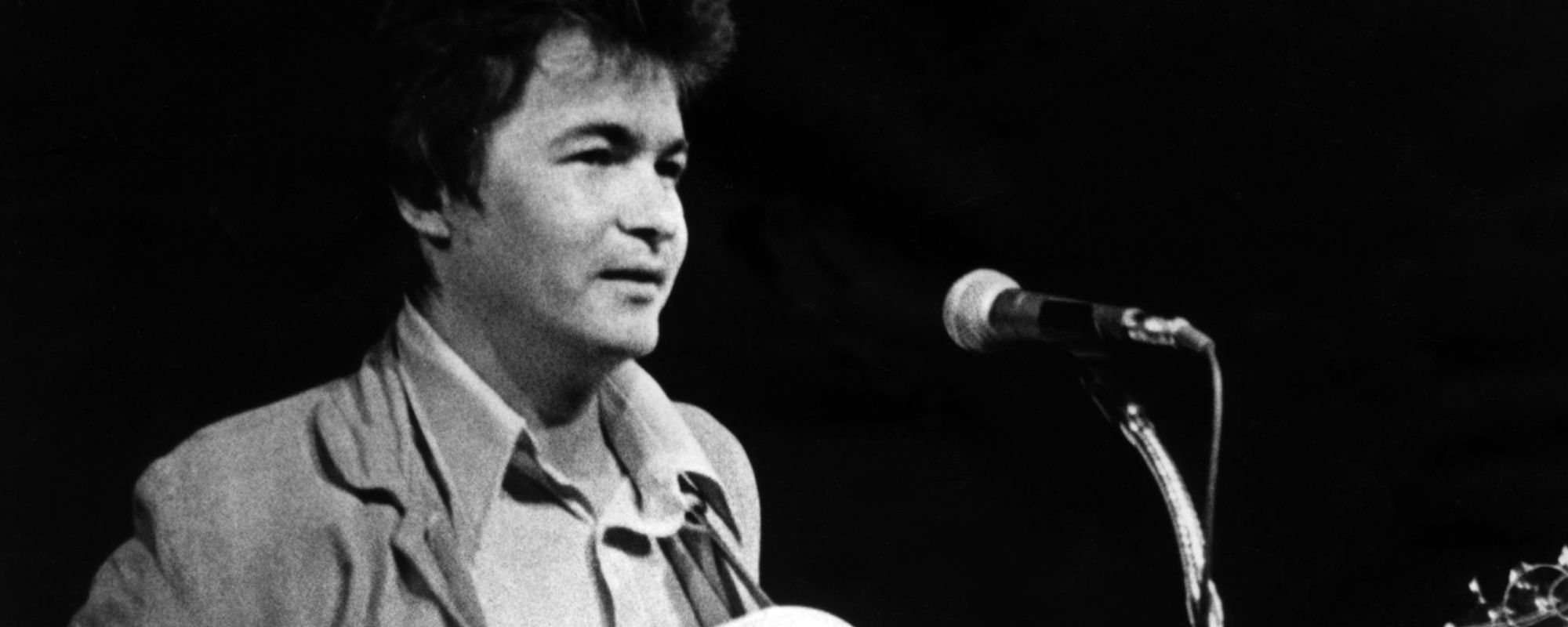

“Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry

The guitar riff in “Johnny B. Goode” as well as Chuck Berry’s signature blues licks form the musical DNA of everyone from Keith Richards to Johnny Thunders to Slash. The iconic intro, borrowed from Louis Jordan’s “Ain’t That Just Like A Woman”, remains one of the most ubiquitous sounds in rock music. But Berry also created one of the first rock star origin stories. An influence wide enough to reach hip-hop, most notably in Eminem’s “Lose Yourself”. It’s hard to imagine The Beatles or The Rolling Stones without Berry, and if either or both bands don’t become popular, then rock history would have looked and sounded very different.

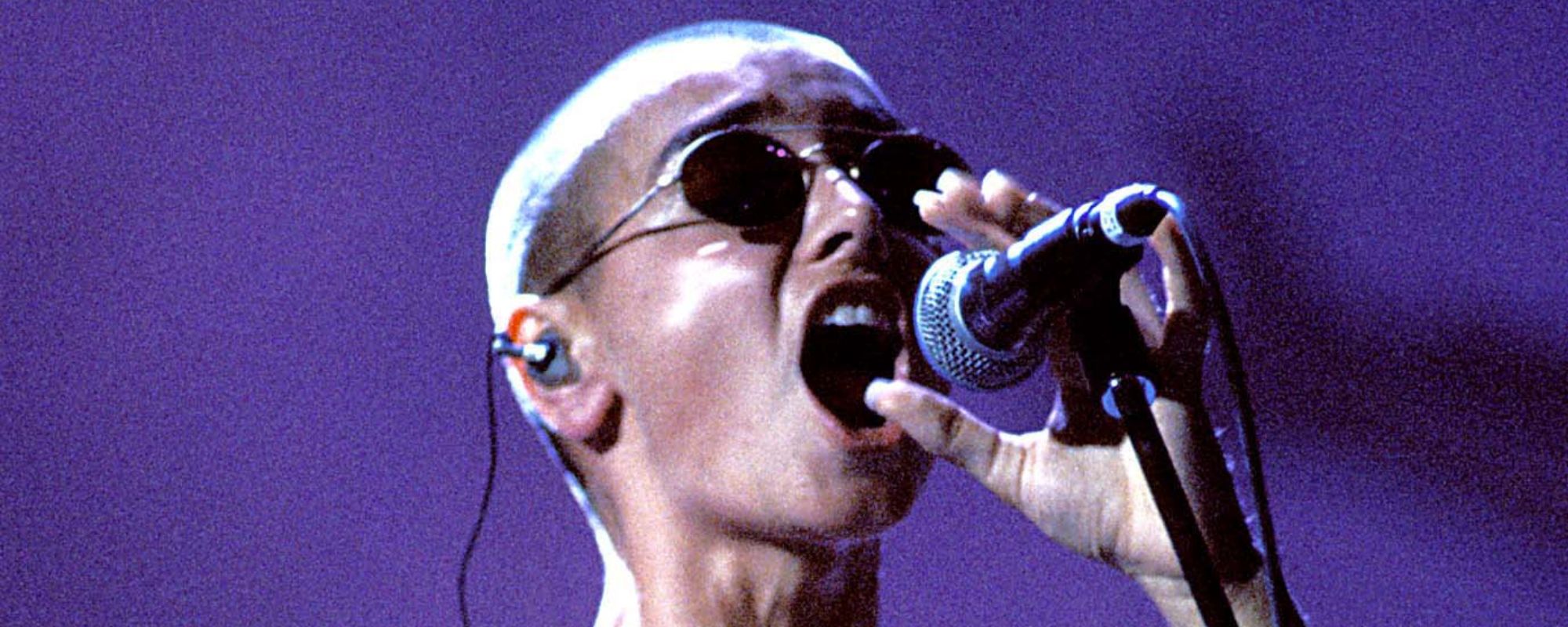

“Mannish Boy” by Muddy Waters

Writing about Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” gives me a good excuse to write about Bo Diddley’s “I’m A Man” as well as Willie Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man” (first recorded by Waters in 1954). The iconic stop-start blues riff in all three tunes became a standard motif in both the blues and rock music. Waters and his song “Rollin’ Stone” famously inspired The Rolling Stones’ band name. But his amplified Delta blues helped shape the Chicago sound that defined everything from the British Invasion bands to Southern rock.

Photo by Everett/Shutterstock

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.