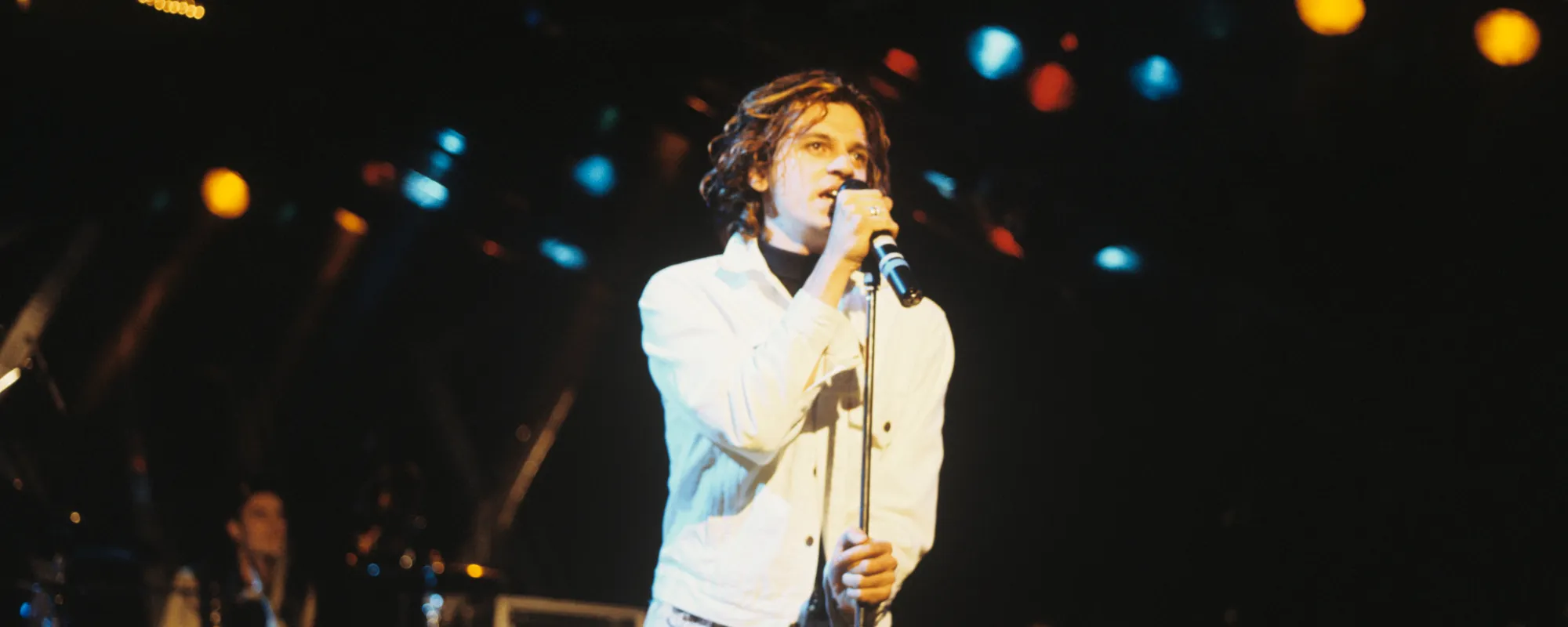

On June 24, 1986, INXS played the Royal Albert Hall in London for the first time. Making note of the band’s show that evening, saxophonist Kirk Pengilly jotted down, “Royal Albert Hall—sold out! Fantastic gig, two genuine encores, and all concerned were happy. Mick Jagger came with Matt Voss … his favorite song was ‘Biting Bullets.’”

That night marked a milestone for INXS, playing the iconic venue, and the Psychedelic Furs, The Cult, and more were also in the crowd, along for the ride. Slowly building off their previous four albums—INXS (1980), Underneath the Colours (1981), Shabooh Shoobah (1982), and The Swing (1984)—their fifth, Listen Like Thieves, not only supplied Jagger’s “favorite song,” but placed the band on a larger map. Topping the chart in Australia and peaking at No. 11 in the U.S., it also gave INXS their first Top 10 hit.

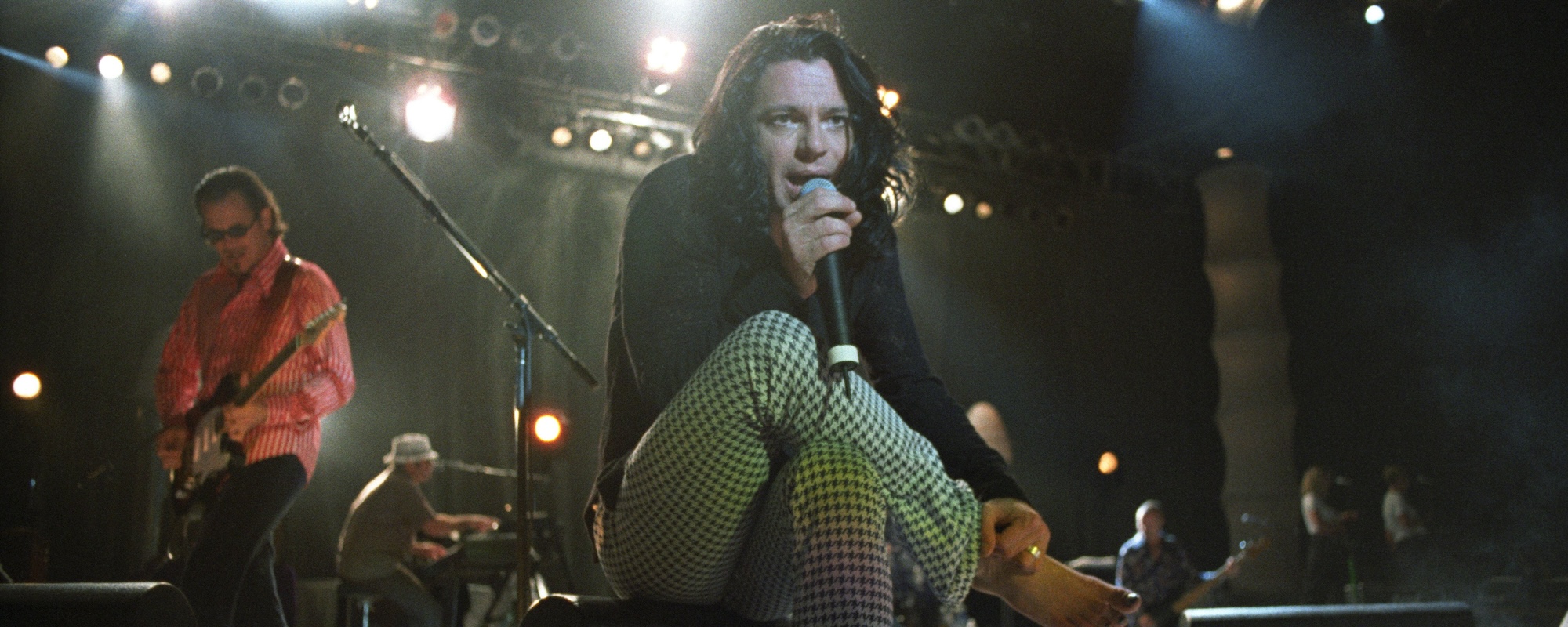

“We decided to write the album in a rehearsal situation, everybody had ideas in their heads, but not many of the songs were written before we rehearsed, and we wrote one song in the studio,” late INXS vocalist Michael Hutchence told Rolling Stone in 1985. “It wasn’t the kind of album where you put tracks down bit by bit. We’ve done the album like a live show, and what is there is there. We want to present this record as a band, the idea of six people playing together and using traditional sounds.”

Released October 14, 1985, Listen Like Thieves was the first in a trifecta of hit albums, followed by Kick (1987) and X (1990), all produced by Chris Thomas, who came in with “marching orders” for the band to rehearse—which they were all averse to—their parts so they could record the album together, live.

Videos by American Songwriter

“We were always pretty crap at rehearsal, weren’t big fans of it,” jokes Pengilly, remembering how the band whined about recording the demos then having to do it all over again in a bigger studio. “But Chris’ point was that he wanted us to learn all our parts so that when we went into the studio, we could all perform the song together,” says Pengilly. “He’d seen us live so many times, and he felt that we’d never really captured how powerful we were on stage, live on a record.”

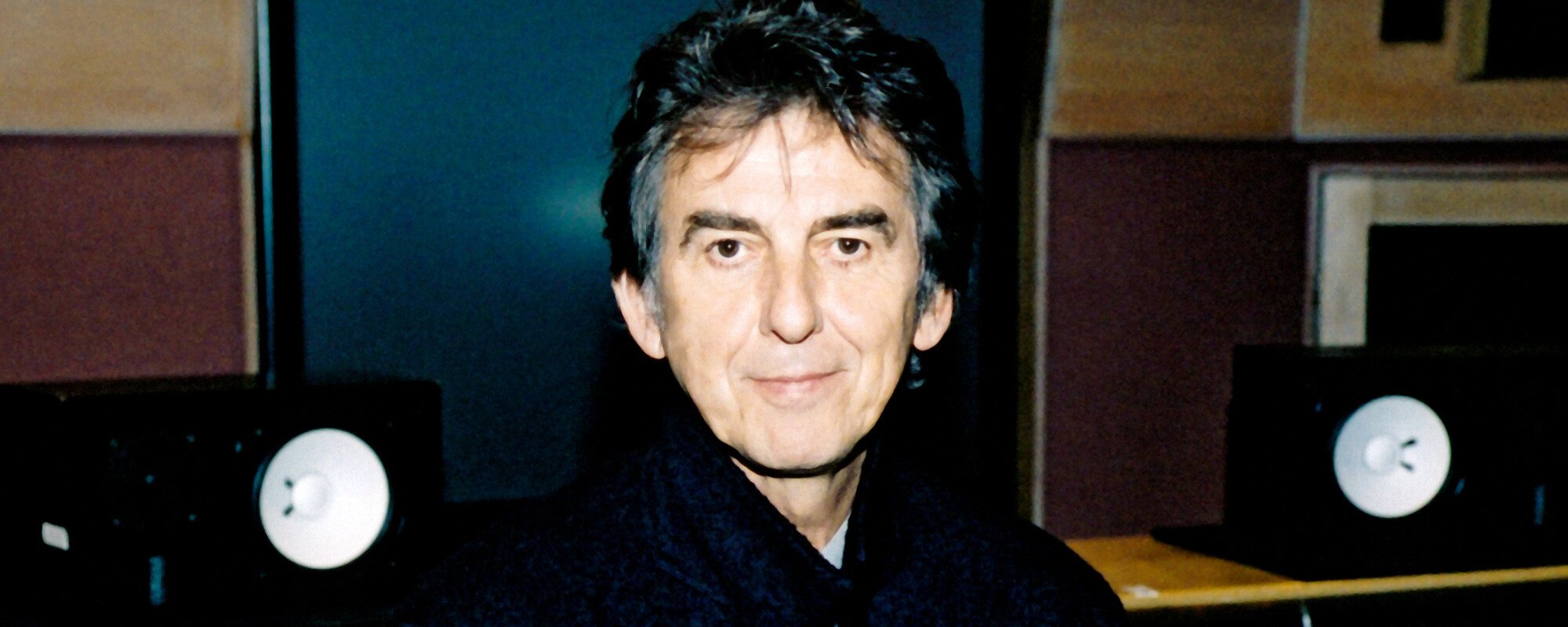

Thomas had his first job working as an assistant for the Beatles’ longtime producer George Martin and sat in on sessions by the Hollies, and went on to work with everyone from Roxy Music, the Sex Pistols, the Pretenders, Elton John, Pete Townshend, and more. He often regaled the band with stories from his past, like the time he chased John Lydon around the ledge outside the Townhouse Studios in London. “Sometimes we’d be listening to him more than we would be playing,” says Farriss. And like the band, Thomas didn’t care to entertain record executives in the studio during recording.

“I always felt after each album that I loved every song on the album, and that’s really important,” says Pengilly. “I think that as an artist, you have to love your songs first and foremost. We never wrote for the fans, for radio, or for anything in particular. We wrote for us. Maybe we were very selfish and very self-contained, but we never let record companies interfere.”

To capture the band’s live sound, Thomas installed a monitor system surrounding drummer Jon Farriss. “His ears must have been through hell,” says guitarist Tim Farriss of the enhanced drum room. “He had giant monitors on either side of him.” Everything felt more experimental with Thomas, compared to their previous albums.

“He’s a classic old-school style producer, trying to get the best out of all of us and very hands-on with arrangements, so it was the perfect scenario for us to have someone like Chris Thomas,” says Pengilly. “It made the recording process that much more intense and exciting.”

Thomas also gave the band a five-day work week with the weekends off, but since they had paid for seven days, individual band members alternated going in on weekends to record B-sides. The band was always “pretty frugal,” says Pengilly, and rarely had any leftover songs except for the first song recorded for each album, which usually got cut. While working on Listen Like Thieves, “Do Wot You Do” was a victim of the “first song syndrome,” but didn’t go to waste when it was featured on the Pretty in Pink soundtrack.

“The thing with Chris was we didn’t really know him at that point, so by the time we finished that record, we got to really know him well,” shares Farriss. “And we wanted to carry on and did the next two albums with him.”

The producer was also adamant that all band members were credited as writers on Listen Like Thieves. Along with Hutchence and Andrew Farriss, who wrote the majority of the band’s songs, everyone had a hand, including Pengilly, who co-wrote “Good + Bad Times” and “Biting Bullets” with Hutchence, and Tim, who penned the only instrumental to ever appear on an INXS album, “Three Sisters.” At the time, Farriss was the first to marry in the band, so his time off from touring and recording was spent with family before writing.

“In some ways, it may have been something that was pushed to a B-side,” Pengilly says of the instrumental, “but Chris Thomas just loved the song and felt it was so important as a balance.”

More pieces came together, including the title track, which started as a bass riff and developed during the rehearsals and into the recording studio. When the band had nearly finished recording, Thomas said they needed another song, which became “What You Need,” something Andrew had in his batch of demos that also began with a bass line and some guitar with a Roland 808 beat.

“I was pushing to turn this into something,” remembers Tim Farriss. “Chris didn’t come in for the day, and the band rehearsed, and we came up with ‘What You Need’ in the eleventh hour.”

It’s hard to imagine that the band’s first Top 10 hit nearly didn’t make it on the album. Released as the lead single off Listen Like Thieves, “What You Need” went to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 and set the tone for what was to come with INXS.

“Had Tim not brought it to our attention, it wouldn’t have made it,” says Pengilly. “ I think it [‘What You Need’] set our musical identity in a way that fusion of rock and funk, which is something that we really expanded on and after the ‘Listen Like Thieves’ album. I don’t think any of us saw that [Top 10] coming, but we were very pleased.”

He continues, “It’s one of my favorites, because it’s probably the only song that we ever did where the saxophone was a featured part with the breaks in between the singing.”

For Farriss, “Same Direction” was a standout track, which the band ended up first recording without lyrics or vocals. “I love the way that song just grew,” he says. “Michael didn’t have a melody or lyrics or anything for it but the music, and I remember being really excited about recording it. Then, as it developed with Michael’s melody and vocals … still to this day, it’s probably my favorite on the record.”

With most songs, Hutchence typically worked on his vocals, lyrics, and melody through the mixing phase. “We had to have real faith that he [Hutchence] would come up with something good,” says Pengilly. “We knew he would. I mean, he was pretty good at that. He was always getting better and better.”

Before hitting with Listen Like Thieves, the band’s third album, Shabooh Shoobah, was one Pengilly considers their first “proper” record. “I thought it was the first real producer [Mike Optiz] that we’d worked with,” he says, “and then we had ‘The Swing’ with Nile Rodgers and Nick Launay, who were both extremely different producers. By the time we’d finished ‘Listen Like Thieves,’ it was like ‘Well, the gloves are off now. We’ve been through everything.”

At that point, there were few boundaries for the band, says Farriss. “We could tell that ‘Listen Like Thieves’ had planted a seed around the world, where everyone was excited about the next record [‘Kick’],” he says. “And there was no discussion about who was going to produce the next one.”

Deciding on the 11 tracks on Listen Like Thieves was also executed by ‘democratic vote” within the band, with Thomas getting some final word. From its start, the band also had a unique internal agreement that half the publishing went to all six members and half to the writers. “We always felt part of it, and we always contributed to each song, and I think it made it a sort of even playing ground when it came to choosing songs,” says Farriss. “Bands would fight [over this], and it was the demise of so many bands over history, but we just had a really good opening forum.”

Once released, the album was supported by four singles, including “This Time,” “Kiss the Dirt (Falling Down the Mountain),” and lead single “What You Need,” which was accompanied by an innovative music video, configured by the band’s longtime collaborator Richard Lowenstein. Using an SLR motor drive camera, rolls of film were hand-painted and pieced together to create the animation and stop motion effects.

Filming the video for “Kiss the Dirt (Falling Down the Mountain)” on the moon plains of Coober Pedy in South Australia turned out to be a less animated experience for the band after their pilot fell asleep during their return flight. All aboard a small, one-engine plane, the band, along with director Alex Proyas (The Crow, I, Robot), flew into the middle of the desert, where portions of the original Mad Max were filmed. Farris remembers everything covered in red dust. “It was kind of ironic,” he says, “since we started our career driving to mining towns, so it was all very fitting.”

Farriss remembers waking up on the plane and seeing his brother Andrew steering while the pilot was passed out. “Everyone on the plane was asleep, including the pilot, and I was like, ‘Hey, what’s going on here?’” recalls Farriss. “Andrew was flying the f– king plane. He’s not a pilot.”

Once he shook the pilot awake, Tim asked if he knew where they were. The pilot said it was all on the chart, which was on the wing of the plane. Adding more stress to the flight, the plane spun upon landing on the runway when a tire blew out. “We did a sort of 360 on the runway,” says Farriss.

The band made it halfway to Sydney and stayed at a hotel for the night since the plane could no longer fly. “Everyone was fine, but it was really out there,” laughs Pengilly. “It was like a ‘Crocodile Dundee’ movie.”

From the band’s near-death video shoot to supporting Queen on the band’s Magic Tour in 1986, more memories flooded in around the making of Listen Like Thieves, and everything that followed. The album set a new trajectory for the band that continued to mount. Yet, the realization that Listen Like Thieves is now 40 is a “weird” one for Pengilly. “It doesn’t compute,” he laughs. “I think we all feel 21, still.”

Circling back to working with Thomas, the band’s 40th Anniversary reissue of Listen Like Thieves was remixed in Dolby Atmos by Giles Martin and Paul Hicks, along with a Deluxe Edition featuring previously unreleased outtakes, demos, B-Sides, remixes, live recordings, a new INXS interview with Paul Sexton, and a rare BBC recording of the band’s 14-song set, Live From The Albert Hall, London, 1986.

“It was amazing to hear the takes that Giles found that are on this new 40th edition, the outtakes that we didn’t use,” says Pengilly. Within the mix of demos and outtakes are “Funk Song #11,” the working title for “What You Need,” and “Funk Song #9” (“Same Direction”), along with added dialogue from the sessions and a radio spot. “What was interesting was that you can hear, especially in the arrangement, how much we fiddled with songs and changed them,” Penilly added. “Each time we did a new take, we would shorten the chorus or do something.”

Thinking of what Hutchence, who died in 1997, might think of Listen Like Thieves today, four decades later, Pengilly and Farriss remember how the singer had developed as a songwriter and vocalist during this period. “Michael had found himself as a performer, and his confidence,” says Farriss. “Michael was always flawless as a performer. He never hit a bum note in his life, and I think he would have loved all the different flavors of songs like ‘Shine Like it Does’ to ‘Red, Red Sun.’ We love the diversity of what we created, and I know Michael did, too.”

Pengilly jokes that the band would have been bored if they went the AC/DC route with more uniform songs and chord progressions. “We love AC DC, don’t get me wrong,” he says. “I think we were really lucky because Michael had a fairly big say in what songs got chosen, and Andrew would have all these pieces of music, and they’d get together. Michael obviously would pick the songs he’d want to bother putting a lyric and a melody, so it had to be something that he loved.

I think he would have loved the album [‘Listen Like Thieves’] today, and where it took us.”

Photo: INXS in black and white (Robert Mort)

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.