I recently went into the studio for the first time in many years. Days before the session, I realized it would require 10 million streams to simply pay for the recording bill. Maybe you can see how that math keeps me up most nights.

Videos by American Songwriter

I hosted a small concert to test out the songs, sharing with the people who had lived the songs with me. Music is an intimate conversation between writer and listener; singing is the most profoundly human thing I do. When I do it right, I am messy, broken, brave, and all heart. Music is belonging and home, heartbreak and hope, love and loss, carefree and unabashed. Human to human. The process of revision with which I write is made of humility and care. It is how I give of myself.

So, AI music. Trained on me. And all your favorite real musicians. Profits going to Big Tech, promising society’s transformation for social good. What’s getting lost in this transaction isn’t just about people who create. It’s missing the very human, “why.” Mass-produced AI “slop” isn’t the real connection; we have looked to music time and time again, but AI-generated junk is now so common that Merriam-Webster added it to the dictionary and counts for a startling one-third of content uploading to streaming services each day. Yes, there are one-off “hits” like the AI-created band Breaking Rust, but beyond these novelties, the sameness and steeliness of it rings loud, an empty hole at the center where meaning and connection are supposed to be.

Mikey Shulman, CEO of the AI company Suno, recently said, “It’s not really enjoyable to make music now … it takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of practice. I think the majority of people don’t enjoy the majority of the time they spend making music.” He’s clearly not a musician. My relationship with music and the time I spend with my instruments is profoundly important to me, like a best friend. Career musicians invest our lives into our craft, even when it’s a struggle. We practice until we have callouses, tour away from our families, and try and try again. We live out of scrappy suitcases because we love making music.

And I don’t hate innovation. AI has a role in music creation as a sketchbook for artists to experiment with new textures and find new ways to build bridges between fans and creators through curated, interactive, human-initiated experiences. It could also offer us innovative solutions in medicine and climate change, which I am hopeful for.

But pushing humans aside for their inefficiency and creative process is a pattern we need to interrupt at first sight. Music–made on human spirit and experience–is being used without consent and compensation to train AI models.

It’s easy to cheer the major record labels for taking companies to court that have allegedly stolen music “on a massive scale.” These landmark cases will, hopefully, produce a ruling reaffirmingthat training AI models on copyrighted music—like “Traveling Alone” and all the stories of all my fellow songwriters—to compete with original artists is blatantly illegal.

Likewise, the recent settlement between Universal and Udio is encouraging, at least in broad strokes. If there was something to settle, it means Udio violated our rights. They surely did. Knock-offs flood streaming platforms, drowning out real songwriters and further eroding already untenable streaming payments. When the dust settles, we’ll see if helping companies like Udio off the mat was wiser than fighting to the end. But being in a band has always been about partnership and collaboration, so we come to the table with open minds.

AI stealing isn’t innovation. We cannot let big tech reduce our music to “data” for an algorithm. Music has the power to make us smile or cry. It contributes to our sense of who we are. Music brings people together, strengthens social movements, and helps define cultures. Allowing algorithms to use stolen human creativity to bring about these emotions and relationships should give us great pause.

So many foundational questions about the health of the music economy and what it means to be human weigh on our present, and I approach them with musicians first in mind in my academic role at Duke University, where I work with a team of faculty, students, and staff to explore what can be done to keep music human. For too long, independent musicians and songwriters have lacked the power to join together and advocate for ourselves, relying instead on the victories of major publishers and record labels. That must change. The streaming era showed us that micropayments only add up for conglomerates and the top one percent of superstars. That broken system can’t be the template for the age of AI.

That’s why the Artist Rights Alliance (ARA), which I co-chair, is fighting for the Protect Working Musicians Act, a bipartisan bill in Congress that would allow us to collectively negotiate the use of our work.

ARA is a proud, founding member of the Human Artistry Campaign, alongside more than 180 creator organizations worldwide, including the trade associations of the major labels and publishers. Central to that campaign and its principles are the core values of consent, credit, and compensation. As new deals and settlements emerge, large rightsholders must be transparent about how their resolutions adhere to those principles. Working out the details takes time, but the music family must engage in this conversation, and musicians must be at the center.

Every music creator deserves a seat at the table. Working together, we can ensure that AI evolves with us, not at our peril.

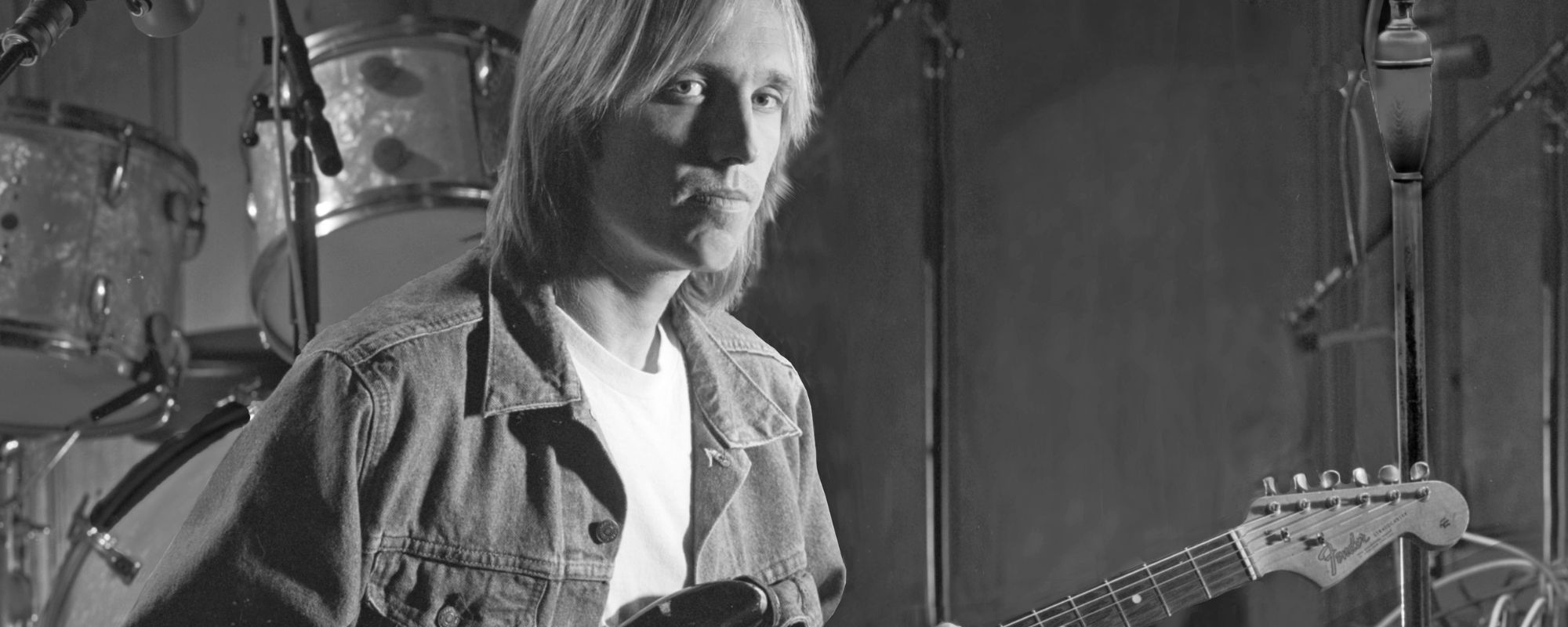

TIFT MERRITT is a Grammy-nominated musician who wanted to be a writer until her father taught her guitar chords and Percy Sledge songs. She has toured around the world with her sonic short stories and garnered a reputation for making her own way and setting an interesting artistic table. Merritt is a longtime student of the creative process with her interview series, The Spark, which began at Marfa, Texas Public Radio. After taking time off the road to raise her daughter, Merritt began work on site-specific projects like the Gables Lodge, set to open next year. She is a Practitioner-In-Residence in collaboration with the Franklin Humanities Institute and the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. She lives in North Carolina with her daughter, Jean. The 20th anniversary edition of her breakout album Tambourine is out now. For tour dates and more, visit tiftmerritt.com.

Photo by Alexandra Valenti

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.