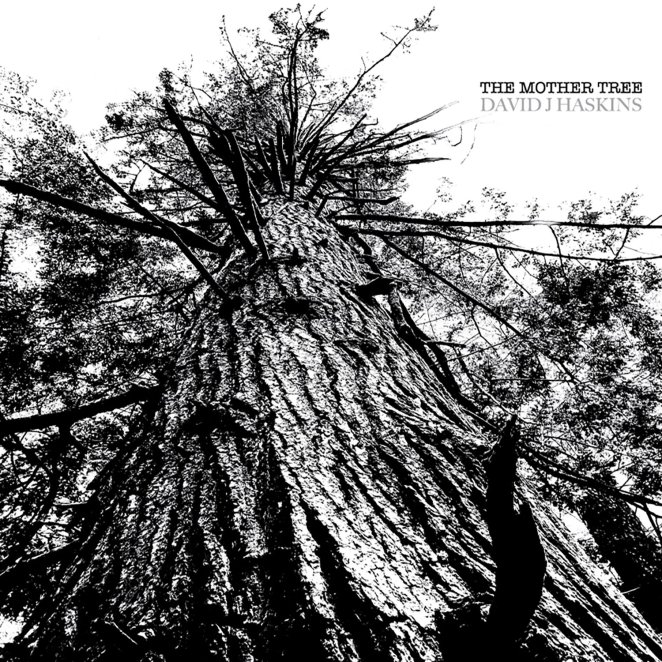

In 1997, following the death of his mother, Joan Nancy Haskins, David J Haskins stayed up for three days writing a poem he wouldn’t release for another 28 years. “That’s the way I deal with death,” says Haskins. “The way I process it is that I write. Sometimes it’s a song. Sometimes it’s a poem.” In this case, Haskins began writing the near-22-minute title track, one of five poems set to music on his new album, The Mother Tree.

“I wrote that as a poem the day after she passed, and then I finished it when I received her ashes,” shares Haskins, who continues the story on the shorter second piece, “Ashes and Tea,” written during a walk back to his apartment after receiving his mother’s ashes in New York City. “It was powerful and cathartic writing it,” he adds, “and powerful and cathartic to record it.”

Produced by Haskins, who plays harmonica on the album, arrangements on The Mother Tree were composed by percussionist Brad Dutz, along with guitarist Tad Piecka, violinist Gregory Allison, and keyboardist Jon Bernstein from the instrumental trio RAQIA, and the album is completed by three additional poems written further back in time.

Written in 1995, “Incantation To Herne” is from a transformative period in Haskins’ life, while he was still living in his hometown of Northampton, England, and immersed in magick. During its recording, Haskins came across an antler left at the studio, a fitting token for the song about the pagan deity, Herne, the horned spirit of the woods. “Elegy to Beale Street” was written during a visit to Memphis in 1990, and the closing “Saviour in the City” was penned that same year while in New York City and meditates on what Jesus’ role would be in the modern-day world.

Accompanying The Mother Tree is Haskins’ book of poetry, Rhapsody, Threnody, & Prayer, a three-part extension of stories of love, lust, loss, and an extension of poetic eulogies for other spirits from his past, including Jack Kerouac, Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, Jeff Buckley, Sparklehorse’s Mark Linkous, Kurt Cobain, Monégasque poet Léo Ferré, William S. Burroughs’ common-law wife Joan Vollmer, and others.

Now Haskins, who recently released “ICE Too Cold To Thaw,” a protest song confronting the experiences of immigrants targeted by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), is working on a new solo album, which he calls a”quite an ambitious, eclectic record,” and will feature a 23-piece orchestra.

Videos by American Songwriter

Haskins spoke to American Songwriter about the poems behind Rhapsody, Threnody & Prayer, one serendipitous night seeing Jeff Buckley live, and making music out of dreams.

How far back do some of the poems in Rhapsody, Threnody, & Prayer date back?

The earliest one goes back to 1978, when I was 21. The earlier ones are the more feverishly erotic ones. Later on, it’s more tempered and refined (laughs). Those early ones stand up. The poetry spans decades, and the last one, Aftermath, was actually written as the book was going to print, and it’s about a memory of something I saw, a motorcycle crash, and I wrote it in one verse.

Why is the book broken into three sections?

It dawned on me as I was collecting these poems that they were in three categories, and it helped to give the book a format. I tend to lean towards Threnody and eulogizing. That’s the way I deal with death. The way I process it is that I write. Sometimes it’s a song. Sometimes it’s a poem. And that was the case with my mother.

Were there any pieces in the book that were particularly difficult to complete?

There’s some about a relationship that’s long past, but it was beautiful at times. Those pieces do capture the reverie of that relationship, so I decided to leave them in. It has an arc. I could say it gets deeper, but I think there’s depth to the other ones. There are a few about childhood. I found it quite a vivid evocation of childhood, and it took me back to the feeling of being a kid in England, in the ’60s. Some are older poems, including Dusk. And Aftermath. When I wrote that, the memory suddenly burst to life vividly.

It’s an excavation, the writing process, and why these things come to the fore. Sometimes it can be a subconscious figure, an image, or something random you see on TV that triggers a memory. A dream can do that. I have a Patreon site, and if I have a very vivid dream, I’ll record a memory of the dream as it just happened, since it’s so elusive, then I set those dreams to music.

The more you record—writing it down or doing a voice recording—it seems to hone your dream memory, and it somehow makes dreams more vivid by focusing on that area.

It seems like the arrangements around each of the five tracks on The Mother Tree had to be very intentional as well.

I’ve always done a spoken word musical piece. Going back to my first solo album (Etiquette of Violence, 1983), there was a spoken word piece, “With The Indians Perminent,” about Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady. On all the albums, there’s at least one spoken word piece, but I wanted to make a whole album, and I wasn’t sure if I was going to do all the music [for The Mother Tree].

With the music, there was another synchronicity: I ran into a friend in an Indian restaurant, Nora Keyes, whom I had produced in the past. She said, “I’ve got a new group. It’s a duo, and we’re playing tomorrow night.” So I went down to this arty cafe bar in downtown LA, and she was on in the middle of three acts, and she was great. I didn’t want a late night, and I was getting ready to leave when this group, RAQIA, started playing, and I was immediately captivated. It was evident there was some improvisation going on, and they were really listening to each other. I met them a few days later, and I sent them a few pieces, and they came up with some music. I didn’t even hear the music till we were rolling, and they just played me a snatch of it, and it sounded perfect.

Throughout the book are more poems about your mother—Forty Stones, Cappricio (Prayer)—and others you’ve encountered and left an impact on you, like Eulogy for Jeff Buckley and Memoria (For Kurt Cobain). Did you ever meet Buckley and Cobain?

I was just affected by their presence. I met Ian [Curtis]. I met Kurt. I never met Jeff. I saw him, and that was by chance. It was pure serendipity that I got to see him because I was actually on my way to see John Cale play the Bottom Line in New York. I was walking through the streets, and I bumped into my friend Hal Willner, who was producing Jeff, and he said, “Where are you going?” I said, “I’m going to see John Cale.” He said, “I’m going to see Jeff. Come along. … He’s on early, and he’s just doing three songs. If you come down, you can see Cale later.” So I went with Hal, and it was a privilege to see Jeff Buckley at his peak. And there was a serendipity or a synchronicity there as well, with Jeff ending his set with “Hallelujah” and Cale ending his set with “Hallelujah.” Jeff Buckley came to the song “Hallelujah” through the version John Cale recorded.

Speaking of New York City, what’s the story behind Wild on 10th & 1st?

That’s just me going out for a night on the town. I met up with a friend in the East Village, and they had to get up early, so I just carried on. I just went to this bar. It was a rowdy, lively place, and I was just in the corner. I wrote that in the bar, so it’s very much in the moment.

Is that how it happens? Do you still find yourself writing anywhere?

Occasionally. Yes. I’m seized by it, then I’ll grab whatever’s at hand—a beer mat, or the back of an envelope … scraps of paper. I love lyrics written on writing paper with the logo on the top, like the Chelsea Hotel. I love those, like Bob Dylan’s lyrics from the ‘60s on the letterhead with the hotel name, the stains, and cigarette burns.

Other times, I’ll just let them ferment. And they’ll just be there, bubbling away, and then suddenly they’ll be a flowering, and it’s usually when I get back home. Then I’ll write out a whole lyric, usually in the flow. Then the music comes very quickly. After that, the music is dictated by the flow and the tone, and the meter of the rhythm of the music, which is dictated by the lyrics.

From Bauhaus to your first album (Etiquette of Violence), Love and Rockets, and other projects, how has your songwriting changed over time?

It is personal, but it’s personal filtered through other stories, outside stories, observations of characters, situations, and newspaper stories. It’s from novels. Then it’s me taking all of that and impressing my own personal story through that filter, if you like. So it’s a bit oblique and abstract, whereas much later on, it became intensely personal and very directly personal, about experiences that I’ve had that affected me, and that’s been a trajectory. Now with The Mother Tree, it couldn’t be any more personal. Being less guarded just comes with gaining confidence. And it’s also one’s disposition. When I made that first album, I was a pretty uptight and paranoid young man (laughs) and wary and cynical, guarded, armored—all of that.

It’s funny when you let all of that go, how music easier it is to tap into some of that deeper stuff.

It’s just having the courage to be vulnerable. It’s also a revelatory process of writing. It’s self-revealing to a degree.

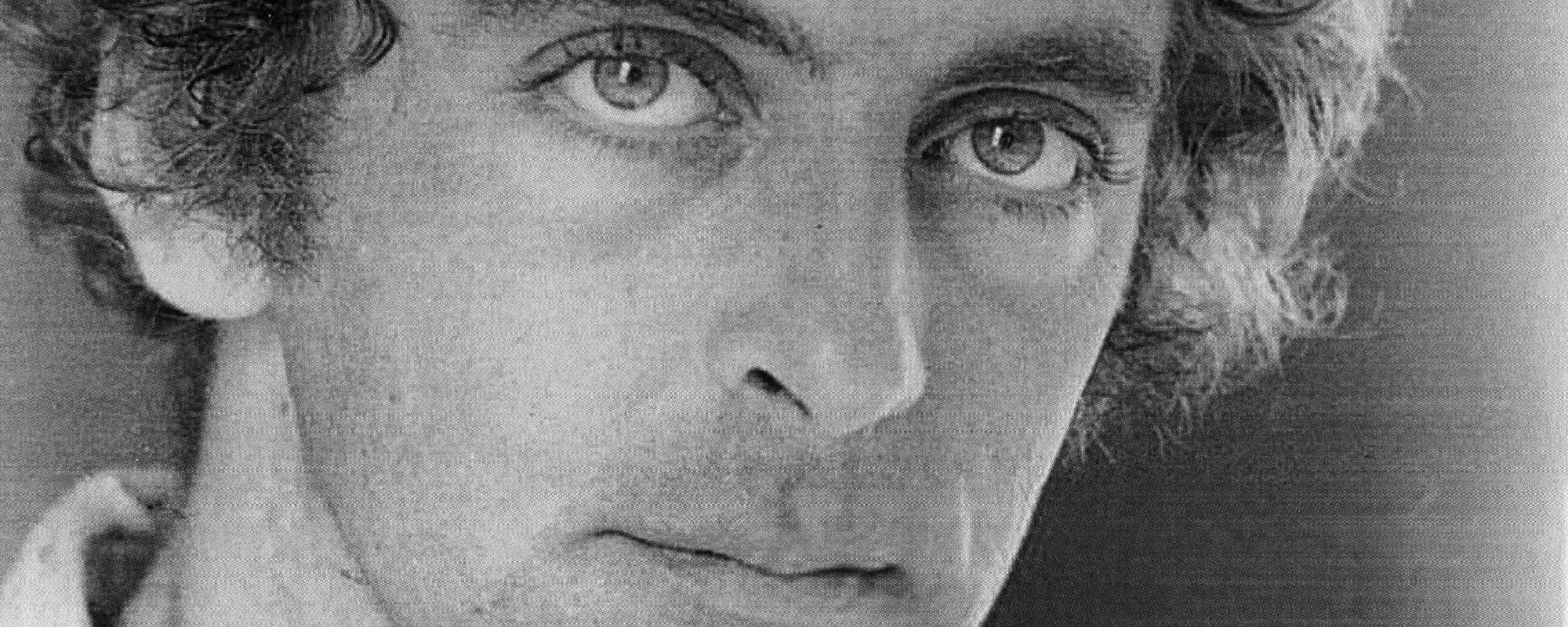

Photo: Sergione Infuso/Corbis via Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.