It was the first day of spring on Yonge Street in Toronto, 1981, when Eddie Schwartz heard a familiar sound coming from the radio at a local hair salon. Flooding onto the street was a song Schwartz had written three years earlier in 1978. Now, it had made its way onto the radio, forcing him to stop in his tracks, frozen in place on the street. “I was standing outside drooling, in a trance,” laughs the Canadian singer, songwriter, and producer, recalling the first time he heard Pat Benatar’s “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” on the radio. “And so they called the cops on me.”

That day, Schwartz managed to dodge an arrest and walked away with his first top 10 hit, along with Benatar. Released on Benatar’s 1980 album Crimes of Passion, “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” went to No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100.

“It was great to hear ‘Hit Me With Your Best Shot’ for the first time on the radio, and they didn’t actually haul me off to the station like they threatened to do,” says Schwartz. “So I guess I consider myself lucky.”

Schwartz’s luck didn’t run out since he went on to write more hits, including The Doobie Brothers’ “The Doctor” (1989) and Paul Carrack’s 1987 hit, “Don’t Shed a Tear,” along with a catalog of songs recorded by Joe Cocker, Carly Simon, Donna Summer, Olivia Newton-John, Rita Coolidge, Robert Palmer, Jeffrey Osborne, Mountain, and Martina McBride, among others.

Between songwriting, Schwartz also maintained a solo career, releasing his debut Schwartz in 1980, followed by No Refuge (1981), Public Life (1984), and Tour de Schwartz (1995). Another three decades would pass before he was ready to release his fifth piece of work, Film School.

Released after a period of severe writer’s block and after years working to defend songwriters and musicians’ rights, Film School is a collection of six character-driven songs that play out like short stories, (or short films) with the dialogue opening on “We Win,” a socio-political snapshot of facing uncertainties during mercurial times: We play it straight, they play the clown / Time to turn the whole damn thing around / It’s come unwound.

Videos by American Songwriter

“The moment of writing ‘We Win’ was profound for me because I found a way to a more hopeful place that helped with anger, sadness and bewilderment at how we got here,” said Schwartz of the song in a previous statement. Also an activist for musicians, Schwartz, who was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2019, served as president of the International Council of Music Creators from 2017 through 2023.

“I felt the message of ‘We Win’ offered some sanity that I needed to cling to, that I needed to find for myself,” he added. “And I wanted to share it in the hope it might work for others as well.”

Throughout the EP, Schwartz takes a less-produced approach, giving his lyrics room to penetrate from “Outbound Train,” “Waters Rise,” “You Don’t Belong,” and the closing “Come to This.” Schwartz also revises a song he originally released more than four decades earlier on Public Life, “Special Girl,” delivering a stripped-back version of his ’80s synth original, which featured Rick Derringer and was later recorded by America and Meatloaf. The “2025” version is a piano ballad that peels back the old story of a woman who meant the world to him.

“The people in the songs face challenges and find ways to deal with those challenges and move forward with their lives, or in some songs like ‘Outbound Train,’ we go along with them on a somewhat otherworldly ride,” said Schwartz. “So I think that’s the common essence of this collection of songs. Also, I hadn’t written a song in quite a few years before ‘Film School,’ so I had to relearn how to do it—I was back in school in a way.”

Schwartz recently spoke to American Songwriter about returning with Film School after facing years of blank pages when he struggled to write, and why, now that writing again may require a songwriting intervention.

[RELATED: Top 10 Pat Benatar Songs (1979-1988)]

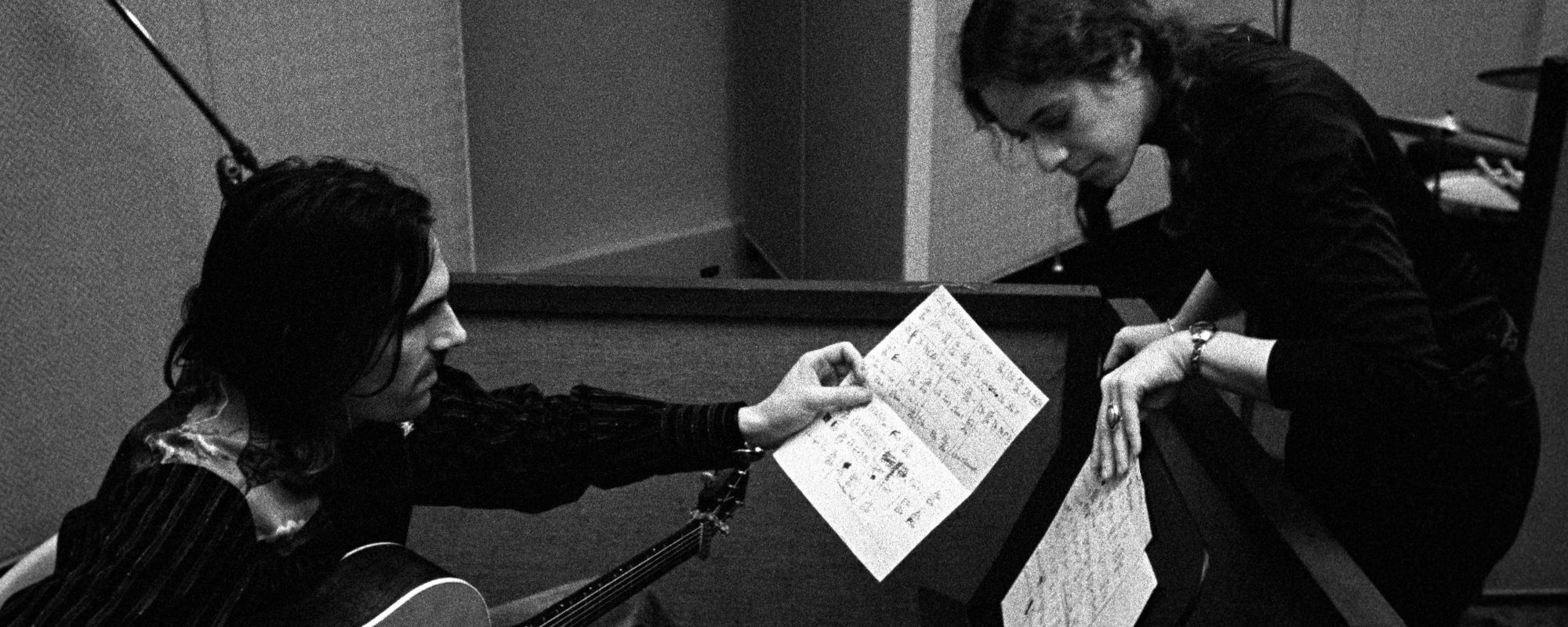

You released “Special Girl” more than 40 years ago. Why did you want to revisit this song in Film School?

I listened to the original at some point and went, “My God, it sounds so ’80s.” Little did I know that, since I released the new version, so many people came to me and said, “Oh, that’s what I love about it … the fact that it’s so ’80s.” I think it’s a song that hopefully stands the test of time, and I wanted to do a simpler piano and vocal version of it. I worked with a great arranger and keyboard player, Lou Pamonti, in Toronto, and he did a great job on it. Sorry to all those people who just want to hear the 1980s version. You can still hear it.

Why was Film School the perfect title for the EP?

I felt they all had a short story or short film subject feel to them. They’re almost like scenes with dialogue where you have a couple of characters interacting with each other. And it was really like going back to school, writing again by myself, and relearning. I’m not the only songwriter who faces this sometimes. You listen to your old songs and go, “How did I do that? How did I actually come up with that?” So you’re constantly learning if you’re not writing by formula, and you’re trying to find new ground to work with.

Some of the songs on Film School are also subtly political.

I’m glad you said that it’s subtly political. I think that’s 100 percent correct. At a time that’s very challenging for many of us, it was me finding what I thought I could cling to in moments of despair, or disillusionment and disconnection from what’s been going on. There’s a real concern about the state of things these days, and the chaos seems to be ever-present. “We Win” is definitely touched by all that. And “Come to This,” the last song on the EP, is probably the most angry, disillusioned song. To one degree or another, most of them are, whereas “Special Girl” is the odd song out.

Let’s go back now. Standing outside that hair salon where you first heard “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” did you realise, at the time, how far the song was about to go?

The thing about being a songwriter is you just never know where it’s going to go. I wrote it in 1978; now we’re in the early spring of ’81. I don’t think anybody told me it was going to be a single. I don’t even recall even hearing the record before that—the songwriter was the last one to know. It was a shock to hear it being played on the radio in this very upscale, quite famous hair salon in Toronto. It was a shock on different levels.

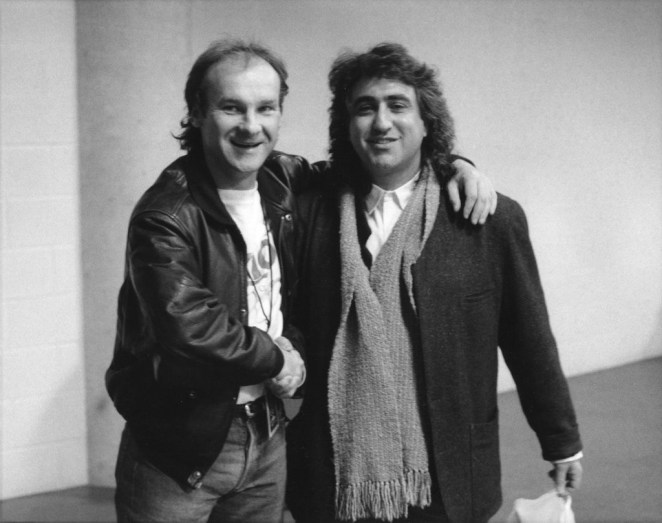

How did it eventually make it into Pat Benatar and Neil Geraldo’s hands?

That was another twisted tale of the music business. My publisher, ATV, hated the song. They were nice people, but they had no interest in promoting it or supporting it. And I disagreed with them quite vehemently. I thought it was definitely a song worth demoing and getting out in the world, and they eventually allowed me to do it—just to get rid of me.

Earlier on in your career, was there a period when you noticed your songwriting evolving?

I think the creative process hasn’t changed that much for me. What I want to write about has changed. In that ’80s world, and before that, there was radio. That was the main vehicle to get your music out in the world. Everybody wanted you to write for the radio. Everybody wanted to know, what’s the first single you could write? You could write 100 songs that they thought were great songs—I’m talking about your record label, if you had a deal, or your publisher. But if you didn’t write a song that they thought was a sure-fire radio hit, you weren’t going to get it to the studio, and you weren’t recording it. So that put a different kind of pressure on me as a writer.

And the thing is, I never tried to write singles. I never thought “Hit Me…” was going to be a single. To me, it was always about writing the best song I could. But once “Hit Me…” had achieved what it did in those early days, people just assumed that I was a guy who wrote singles. So I was kind of on this treadmill, because that’s what they’re coming to me for. And there are worse problems in your life than people coming to you after you’ve had success, because they want more of the same. But it did influence the process. I just tried to write good songs that would appeal to people. So that was always my modus operandi. And that’s still what I want. I want to write something that’s real for me in the hope that sharing it will be real for other people, and cathartic in some way.

Then, there was a block of time when you were burned out and stopped writing. What happened?

I moved to Nashville from Toronto with my family, my wife, and two young kids in 1997. In Toronto, I was mostly writing by myself, or maybe with one other person, an artist, guys like Lawrence Gowan, the lead singer and Styx, and David Tyson, who produced a lot of great records and is a great keyboard player and songwriter. And when I got here, there was a whole other approach to writing songs, which was a sort of industrial, kind of an industrial process, where I would do two sessions, two writing sessions every day, one from 10 till one. Then take an hour for lunch, and then write, write another song from two till five in the afternoon.

I was writing for a number of years, doing that with some interesting results, but I felt that it wasn’t I wasn’t doing my best work in that environment, although, you know, I got some good cuts that I’m very proud of and wrote with some great people, like Gary LaVox of Rascal Flatts, but I just got burnt out on it. I went back and tried to write the way I used to write, just on my own, and I just couldn’t do it.

Did you try to break away from the Nashville writing scene at any point?

Somehow, I was screwed up by this kind of Nashville process, which works for lots of people, and they do very well, but it just didn’t work for me. I couldn’t write at all, which is when I got involved with advocacy for songwriters’ copyright. There are always people who want to use our music but don’t want to pay us, so that was a very interesting journey, and it took me all around the world. I met songwriters and composers and artists from around the world, and I went to various countries to defend and argue for copyright and do right by music creators and by rights holders as well, so that occupied a lot of my time for another six or seven years.

When I stepped down late last year, I gave it another go, and I sat down and tried to start writing some songs again. And it was difficult, but the first one I actually was able to complete was “We Win,” and that was a real breakthrough for me. It was like, “Oh my God, I can actually do this again.” It was exciting, and there were a number of other unfinished songs I was working on that are on the EP.

As an advocate for musicians’ rights for many years, do you still think it’s a good environment for songwriters now?

Well, the economics of it have always been really hard. It’s always been a nickel-and-dime business. Royalties come in dribs and drabs. But if you can put them all together, you can have a middle-class living, which was amazing to me, that I could actually support myself, not lavishly but comfortably as a songwriter, at that time. It’s so much harder now with streams; it can be pizza money. But there’s a lot to be said in terms of the freedom you have as an artist. You don’t have a label necessarily dictating what you should be writing, and you’re not looking for that one single that’s going to break you on the radio. But it’s still very hard to support yourself and to sustain yourself as a music creator these days, and that’s a shame, because people are still making a lot of money from the music that we create as songwriters and artists. We just don’t seem to be getting very much of it, and that’s problematic and not getting any better.

On Deezer, one of the bigger streaming services, something like 30 percent of what they get is already GenAI-driven and created. And that’s pretty scary, because it’s GenAI trained on the songs of real music creators, real songwriters, and artists. So they exploited what we do to train the machines. And now the machines are doing it and already eating pretty dramatically into the revenue that you can get.

What are you working on now?

I’ve been working on another song that I want to finish. It’s compulsive. I can’t take any credit for it. It’s an addiction of some kind.

Does songwriting feel like that “addiction” again for you again?

It’s always been my main coping mechanism for the world. When I think about all the songs I’ve written, I think they were all basically written at a point in my life when I was trying to deal with or process something. “Hit Me with Your Best Shot” was written at a time when I couldn’t get in the music business. I couldn’t get my foot in the door anywhere, and I was just about to give up and go back to school. My mother wanted me to go to law school, and I just said, “No, I’m going to pursue a musical career.” So, “You’re a real tough cookie…” Well, the tough cookie was kind of the music business or the world in general, where I couldn’t get a break. If I go through every song I’ve written, there is a pattern. It was some sort of musical answer to whatever is going on in my life that I needed to address.

I’m compulsive to the point that members of my family are concerned about me. There may be a songwriting intervention of some kind around the corner. They encouraged me to write again, and now that I’m writing again, they created a monster. It’s just so important to me. It’s always kept me alive.

I started writing when I was very young. I came from a pretty dysfunctional family, and I don’t think I could have coped with those teenage years and growing up at any point in my life … songs were a big part of keeping me alive, emotionally and in more existential ways. There were years when I drove a cab, moved furniture, worked in a worked in a record store. Then, there were years where I made a living as a songwriter and as a producer. At the end of the day, I was very fortunate to live in a time when you could make a living. As hard as it was, there was still enough of a functioning market, that if people did your songs, you could support yourself. And at the time, we never thought it would go away, but looking at it now, it feels like a distant dream in some ways.

Photos: Courtesy of Eddie Schwartz / Reybee Inc.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.