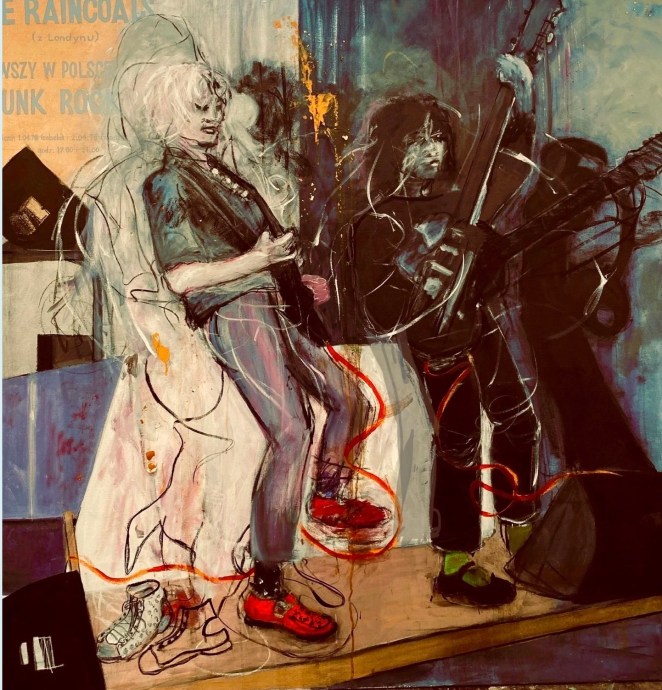

Gina Birch has always been in the middle of an artistic revolution. During the late 1970s, Birch and her art schoolmate Ana da Silva co-founded one of the earliest and most influential female-fronted post-punk bands—foremothers of the latter Riot grrrl movement—after catching a life-changing performance by the Slits. After years of moving through several musical projects, Birch returned to school in the early 1990s to study film at the Royal College of Art, and directed music videos for New Order, the Libertines, Daisy Chainsaw, and the then-freshly reunited Raincoats. After forming the Hangovers in the mid-‘90s and continuing to play live into the 2010s, Birch revisited her other young love in 2014: fine art.

“I went through four years of art school without ever painting at all, so when I came back to it, all those years later, I felt like I was picking up where I left off at 18,” says Birch, now 70. “My skill was my 18-year-old self, but my brain was going off, and I had all these stories to tell with paint.”

Immersed in making new art, Birch also released her debut solo album, I Play My Bass Loud, in 2023, then immediately got to work on her second, Trouble (Third Man Records).

“The record title refers to all the mini revolutions that have occurred in my life,” said Birch of Trouble, “not following the usual paths, falling down holes, making the same mistakes over and over, trouble of being a young woman at a time our options were generally secretary, mother, or sex worker. Trouble I’ve caused and trouble I’m in.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Produced by Youth (Paul McCartney, Peter Murphy, The Verve), who also worked on her debut, Trouble chronicles some of the offbeat, maddening, and exploratory episodes of Birch’s life from the spaced-out dub of “I Thought I’d Live Forever” and dream-goth chants of “Happiness.” Electro post-punk pulses through “Causing Trouble Again,” calling out women who broke barriers—Joni Mitchell, Nico, Nina Simone, Louise Bourgeois, Grace Jones, Dolly Parton, Kathleen Hanna, and so on—and also features some prominent females in the video, including The Raincoats’ da Silva.

Multiple personalities come across Trouble with a sweetly distorted melange of strings on “Cello Song,” Birch’s feminist appeal—Paint drips down like flesh and blood onto the floor / Her almost smile is blurring / She’s afire like lightbulbs flashing / She’s a fighter and she is raging—to the robotic dance of “Keep to the Left, reggae-fused “Doom Monger,” and abstract hip-hop of “Don’t Fight Your Friends” and “Nothing Will Ever Change That.” By its end, “Sleep” pulses into desire and obsessions—I wanted to make you mine … father of my baby—through “Train Platform,” a song inspired by Birch’s husband Mike Holdsworth.

Along with Trouble, Birch is in the midst of a new artistic zenith with her visual art soaking into the personal, activism, punk portraiture, and other human conditions. In 2023, Birch showcased a portion of her collection of feminine figures in London, aptly named after the Raincoats’ 1983 The Kitchen Tapes track—and the first song Birch ever wrote back in 1977—“No One’s Little Girl.” In 2024, Birch reappeared at the Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990 show at Tate Britain with a Super 8 film entitled 3 Minute Scream, which she originally shot during her earlier school days at Hornsey School of Art.

After making her way across the U.S. with a run of shows in 2025, and before continuing on tour in the UK and Europe into 2026, Birch shared what it means to have opened some of the first doors for female punks, if there’ll ever be a Raincoats return, and how she’s painting new stories.

American Songwriter: By the late ’70s, there was this perfect storm of female-led punk and post-punk bands. Did you know what an impact you were making at the time?

Gina Birch: We didn’t really know it was special for all this time, but we were very lucky that we were the ones there, doing it and feeling it. There are these time capsules where something just lights up. And if you happen to be there in that moment, you’re the moth to the flame. That sounds a bit deadly, but we were just drawn to it. And I was lucky to meet Ana [da Silva] because I was kind of quite naive. I liked Bruce Lee films and ska music, and Ana was a little bit more poetic. But I think we both brought to each other the opposite sides. I was more fun and crazy, and Ana was more serious and poetic. And I think either one of us on our own wouldn’t have kept the strength that the Raincoats had because of our two almost opposing personalities. We both got a little bit of what the other had.

AS: Sometimes you recognize the enormity of a moment after it’s all said and done. Then, fast-forward to the early ’90s and the Riot grrrl movement, the direct offspring of bands like the Raincoats and the Slits.

GB: It’s true. You light a little flame, and the fire can start. And I think that’s what happened, and it was incredible. We are very proud that we were the ones to help it. When Riot grrrl happened, the mirror was held back up to us, and we were like, “Wow.” We knew at the time that there were some people who thought we were good, and sometimes we’d get stopped in the street by people saying, “I love the Raincoats,” but that was quite rare. And then when Riot grrrl thing happened, and the ripples of what we’d done had been taken very seriously and almost magnified and held up and scrutinized and examined. We were very impressed with what a lot of those young women were doing, too, their bravery. We’d given them some kind of permission to do it. But their bravery seemed so much stronger than the fears we felt [during the Raincoats’ early days], in a way. I suppose because the world was so small in which we were functioning back then. Things were on photocopiers, or they’d be like 100 people at the gig, or smaller. Everything was word of mouth. What we were doing was very tight and small and compact, but when Riot grrrl happened, it was getting bigger and bigger.

AS: There was a huge part of your life lived before your first album (I Play My Bass Loud, 2023). How did Trouble come out of all of this?

GB: Once I Play My Bass Loud came out, I just sat down and thought, “Well, I’d better get writing on a new album.” And I just let thoughts meander through my head. And if something made me laugh or made me cry, or arrested me in some way … or something stupid, like when you’re driving, and the indicators going “tick tick tick” and follow a rhythm like “Keep to the Left.”

That [song] came and then “Happiness.” It [“Happiness”] came out of a few things, like this Chinese restaurant sign (a red sign with gold letters that said “Happiness”) that I used to see every time I drove into London on the way back from my mum’s. But the other part of it was we had an overground pool in the garden in the summer, and we’d fill it up and heat the water slightly. Then, we’d have these long noodle things, and we’d run around, jump on the noodle, and then laugh our heads off. Sometimes those were the happiest moments, because you’re just laughing so much and you’re being spun around in the water. For me, it was the epitome of joy.

I know it’s frivolous in a way, but it was often with good friends or family, and a lovely thing. That’s why it’s like a whirlpool of laughter in the song. Sometimes sunshine bursts right through me. Sometimes you’re bursting with happiness. But I get the opposite, too, so I tried to tune into those things. There are a couple of love songs on there, too.

AS: Is “Train Platform” one of them?

GB: That was about the train I used to pursue my now-husband. We were both working at Rough Trade, and I’d left a bit early, and I got halfway home, and thought, “I bet he’ll come along on the train soon.” So I jumped off the train and waited on the platform. We’ve been married for years, but I’ve never really written a song to Mike before. It then goes a bit off because it didn’t happen quite like that, but, you know, we’re allowed a little poetic liberty.

AS: Were there any songs you had to leave out?

GB: I wasn’t even sure when I’d finished the album that it was really finished. There was another song I was desperately trying to get into the album, which is called “I’m an Artist.” I started writing “I’m an Artist” because Ana [da Silva] had a song, and I told her, “I love that song you have, ‘I’m an artist.’ She said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about. … I’m singing ‘I’m in darkness. I’m in darkness.’ So I decided to write “I’m an Artist,” because I’ve never really called myself an artist. There’s this incredible modesty of the English. Only someone else could say I’m an artist. I couldn’t call myself an artist. Now, approaching this ripe old age, I can finally say I spent most of my life pursuing things … ways of looking at things from a creative perspective. I’ll take something and turn it around, look at it, and try to work out how it could be part of a creative idea. I am undeniably an artist. I’ve trained all my life to look at things in that way. So I’ve written a song, but I just couldn’t quite get it done. It’s nearly done so maybe it’s for the next album.

AS: You mentioned Ana da Silva. Do you think the two of you might work on more music one day?

GB: I don’t think so. I don’t think she wants to, really. I think she’s felt like she can do her thing now, and she’s happy that I’m doing my thing. And sometimes I’ll ask her, “Do you want to play on this?” I’m probably a bit more gregarious than Ana and bursting into things. Ana takes time to decide what to do. I’m quite spontaneous. She’s never really expressed any desire to do anything in Raincoats, because we both have such a stronger identity of ourselves now.

AS: Has songwriting changed for you over the years?

GB: Technology has changed it. Technology has changed the world in so many ways. In the old days, you might have had two cassette players, and you would record something onto one and then put something on the other while recording. I remember all sorts of songs that I started to write. I had all these songs that I thought were too stupid, and when I think about them now, I’m like, “Why did I censor myself?” I had one about pots and pans and sinks and dishes, and if I had three wishes. I was living in my squat, and there was all this washing up in the sink. I’d written all this stuff about it, and I thought, “I can’t sing that.” But now I don’t censor myself anymore. There’s more confidence. In those days, we used to say “personal is political.” There was this madness in my head that could not be allowed to turn into a song. But now I realize it connects with the madness in lots of people’s heads.

AS: It’s funny that you use that word madness. With all the different arrangements, there is a bit of musical madness throughout Trouble.

GB: I like weird noises flashing across the spectrum. I like the whispering and the yelling. I remember when I was 9 or 10, and went to my brother’s best friend, and he had his first pair of stereo headphones. I put on the headphones, and these sounds were whizzing across from ear to ear.

AS: How has your visual art become another form of expression and storytelling for you?

GB: I became a painter about 11 years ago. I was trying to paint women who had done interesting things, and women who had struggled and failed, women who’d been shot down. When I’m painting, I paint stories over each other. It’s almost like I’m making an animation. Somebody might look really amazing and beautiful, then I might put charcoal on, then water, and things start to drip and change and evolve and disappear. I was becoming a kind of Dr. Frankenstein. Sometimes they [figures] were fighting through and would peep through, dripping. It’s like covering up the prettiness in a way, or the conceit.

The thing is: the only limits you have are the ones you put on yourself. You can feel old at 28 and think, “I couldn’t possibly train as a lawyer, or I couldn’t possibly start a band, or I couldn’t possibly go to acting classes, or I couldn’t possibly take up painting.” But you can. You can do it at 28. You can do it at 58. I went to painting classes when I was quite old. I painted at school, but when I went back to painting, I was like, “I love this paint. I love the way paint brush drags through one color and pulls into another.” I nearly died and went to heaven. And I can tell stories with paint. I can make big dark charcoal lines, yellow and red and green—and faces and buildings, landscapes, murders, and births.

I went through four years of art school without ever painting at all, so when I came back to it, all those years later, I felt like I was picking up where I left off at 18. But I had my brain. My skill was my 18-year-old self, but my brain was going off, and I had all these stories to tell with paint. How brilliant.

I’m going back into my studio again very soon. I’ve got some paintings that are waiting for me. They’re saying, “Where have you been?” They’re calling me back now.

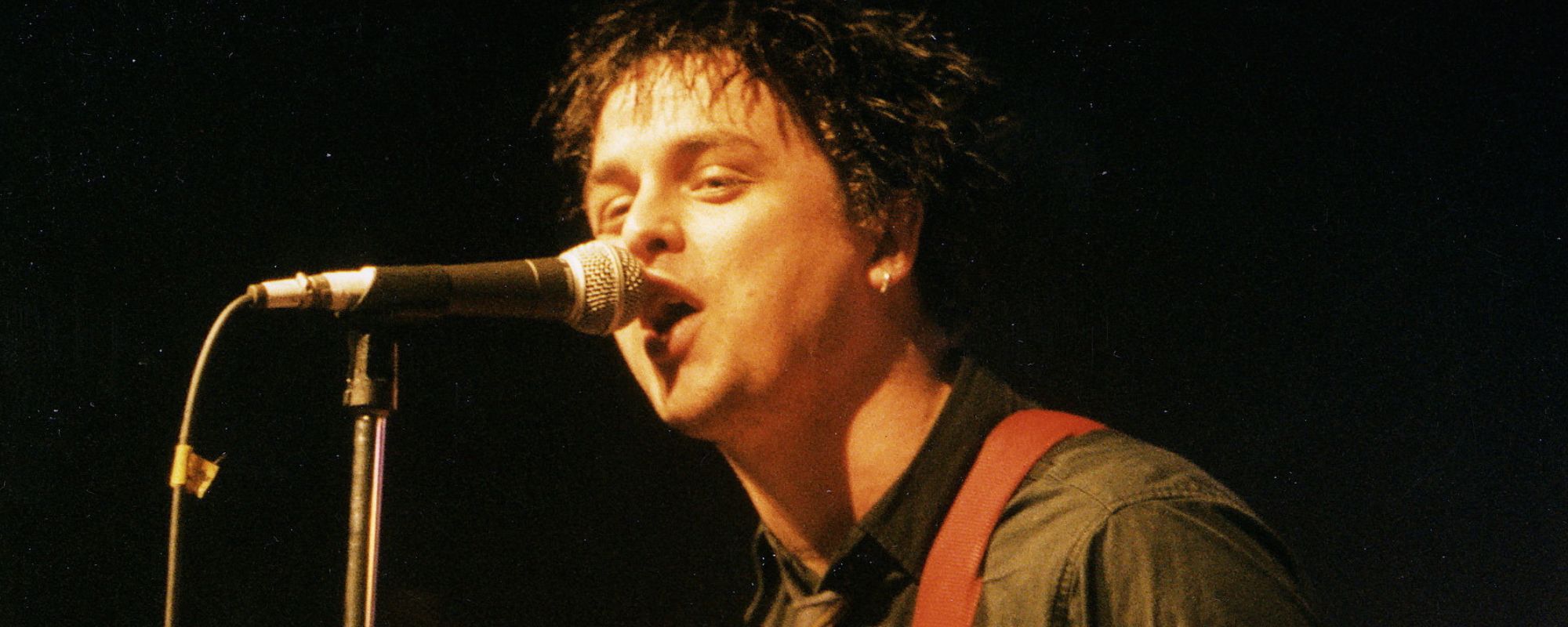

Main Photo: Dean Chalkley

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.