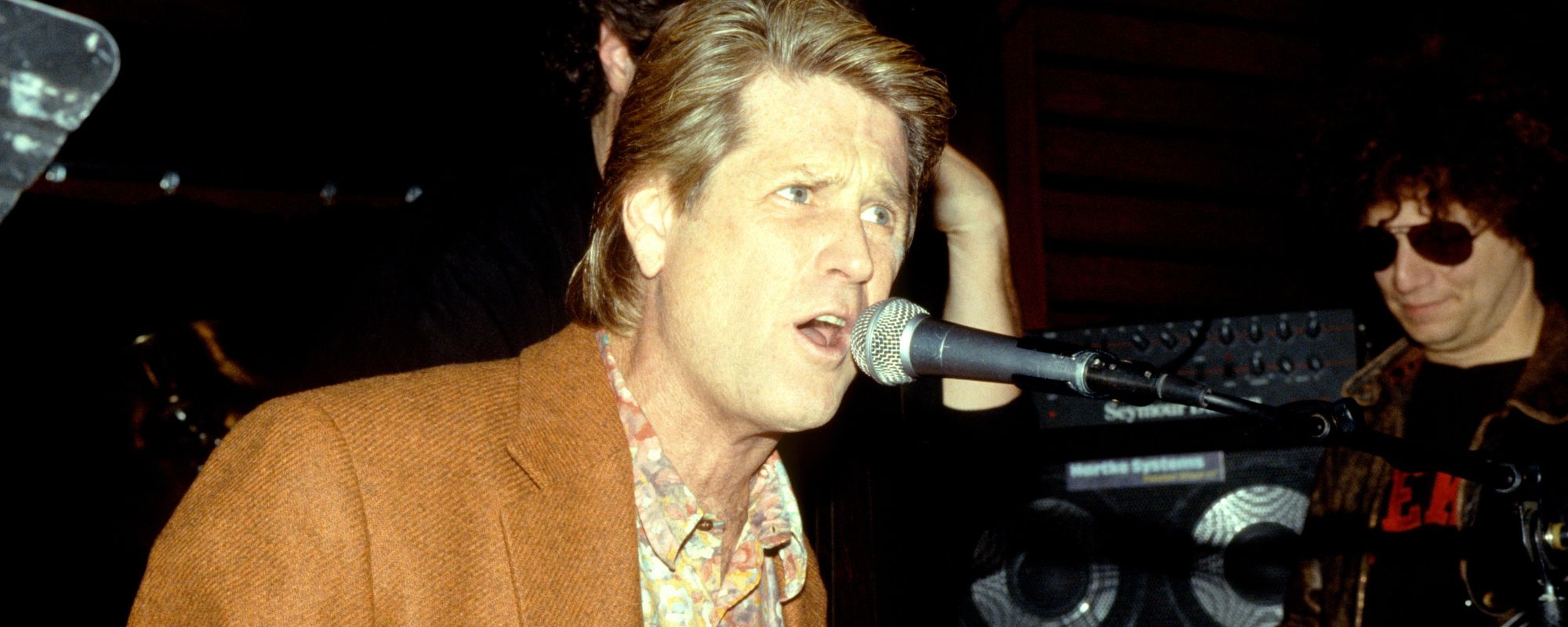

You may know Peter Holsapple from his work on the road and in the studio with R.E.M. and Hootie & The Blowfish. Or, maybe you know him from his bands The dB’s or Continental Drifters. Or, his duo records with Chris Stamey. Maybe you know him from his collaborations with John Hiatt, Indigo Girls, and The Troggs. Peter gave our American Songwriter Membership some insight into making a life in music and his latest solo album, The Face Of 68.

Videos by American Songwriter

Editor’s Note: Peter Holsapple provided this guest post for the American Songwriter Membership. Become A Member and get exclusive content, including access to the songwriters behind hit songs by Ed Sheeran, Bonnie Raitt, Morgan Wallen, Guns N’ Roses, and more. You can also enjoy access to special events, song feedback, giveaways, tips, and a community of songwriters and music lovers!

Peter Holsapple’s Career Has Been an Eclectic One

Welcome to my dichotomous life! Don’t know my name? You’re not alone, despite my 50-plus-year career making music. “These are the breaks,” as Kurtis Blow said, and I’m more than okay with it.

The highest-profile parts were as the utility musician with a popular rock band, which I did with both R.E.M. and Hootie And The Blowfish for tours and recording. The songs were familiar and beloved by their audiences, and I got to share in that love when I was onstage with them for many years. It was a great way to make a living.

Somewhere in the middle are decades with a couple of fantastic bands, The dB’s and Continental Drifters, with whom I shared a puzzling lack of commercial success but an undeniably superb canon of memorable songs.

The lowest profile may well be my own solo career, which I neglect for years at a time, popping my head out just as another new social media platform comes along to fumble along with.

Tour bus versus car with trailer. Madison Square Garden versus somebody’s cozy backyard. Consistently inconsistent.

It makes no difference if it’s 20 people or 20,000… actually, I lie, there is a difference; but it has all been enjoyable. I get to pick up a guitar or push the keys of a Hammond B-3 organ for a couple of hours a night and make the vacuum of playing alone disappear.

Words of Wisdom for Making It as a Musician

The energy that the audience returns to you is palpable and potent. It’s an unforgettable experience, and you can make it like that for yourself at every show, I’ve found, if you can push your worries out of the way and become immersed in the sound. The Byrds called it “relaxed and paying attention.”

When I aid and abet another artist on a show, I always listen most closely to the singer, as that’s most of what the audience’s impression will be of the performance, to be frank. I’m not dismissing the contributions of rhythm sections or guitarists, just acknowledging the vast power of a Darius Rucker or a Michael Stipe. They communicate in words wrapped in beautiful melodies, and it’s up to the rest of their accompanists to build a complementary frame around that portrait.

There is an understanding that whatever my parts are going to be, they will be supplemental and discrete. I don’t like to leave sonic fingerprints. Part of that is because I’m not a world-class soloist on any of the instruments I play, but I’m good at adding texture and support to the more prominent elements of a song, which comes from being a good listener. I feel comfortable in my instinct as to what instrument works best on what song. By not being emotionally attached to someone else’s song the way I might be with my own, I think about it differently.

Once The Beatles changed my world on The Ed Sullivan Show when I was eight, I went to work learning the guitar. I also sat at the piano and made a connection between what I was hearing on both instruments. I sang in my church choir. As soon as I could get lessons at school, I took up string bass and snare drum. I’ve never gotten very proficient at any of them. I’m a late bloomer on lead guitar and have never gotten the hang of pedal steel or banjo. George Harrison had the right idea with the sitar, realizing his limitations and lack of time to make marked improvement as a player. But I still linger a little over those Sho-Bud steel guitars for sale online.

I’m satisfied being a competent player on a bunch of odds and ends. That has made me a really useful commodity for years. My business card has read “I make you sound more like you do” which is a good credo to live by.

But my songs have been what I’m proudest of in my musical life.

I am not sure where they come from, but they have appeared with some regularity since I picked up my mom’s abandoned Silvertone guitar and have yet to cease.

I found, in a folder in my late father’s desk, a neatly typed, center-justified set of lyrics from around then which he’d transcribed. Called “Good Wishes, Dirty Dishes And Goldfishes” it had verses referring to each of those items, somehow also attaching a kid’s presumption of what true love was also all about (slightly presaged my attempts to be a pre-teen blues guitar phenomenon, unqualified though I was).

I spent more time in those adolescent days trying to become more competent and confident on the guitar and piano than I did working on songwriting. But it helps to know how to use the tools to get the most out of them.

I was playing in a band with Mitch Easter and Chris Stamey in 1972. Mitch had already been writing songs and had cut some in a real studio. Obviously, he was miles ahead of Chris and me in that respect. We recorded a few of Mitch’s songs at the same studio; I contributed a tune that was an undercooked travelogue about the local hippie hangout, Reynolda Gardens. The music was very heavy guitar rock, and none of us could sing worth a tinker’s dam. The album’s collector’s item status fifty-plus years on is determined by its scarcity rather than for any great musical worth. But it was a good place to start as an intrepid startup songwriter.

In 1973, Little Diesel was probably the first NC band to be informed by Nuggets, Lenny Kaye’s 2-LP compilation of seminal garage rock. In that spirit, I wrote us a yearning ode to young romance gone bad. (An ongoing lyrical theme of mine for years to come.) I also wrote a tribute to the local X-rated drive-in theater. We had the business acumen to only press up twenty-five 8-track tapes that we distributed amongst our friends, and damned if it didn’t get reissued decades later..

I moved to New York in 1978 and joined The dB’s. Chris and I only wrote a couple songs together, and I never got the hang of co-writing. But we were so productive then, and we’d become identifiable writers (his songs playful and experimental, mine rootsy and jangly). When Chris left in 1984, I wrote the last two albums’ songs and felt I’d gotten comfortable with what I was producing.

By 1987, I’d moved to Los Angeles and joined up with a songwriters’ collective called Continental Drifters. There were so many excellent writers in that band. I got a little lazy about my turnout, although I’m represented on each of the band’s albums. Those songs were unlike my previous band’s output significantly.

And bands break up and reunite sometimes.

But you can always be a solo artist! Even a new artist again at 69 years old. You don’t write the same songs you wrote at 22 (or 8 or 45), so long as you’re okay with that…

This time out, with The Face of 68, I wanted to make sure I had the best collection of songs and that they got played with energy and enthusiasm. They were, and they did. I’ll get to play them to people who know me and people who are just now hearing about me. Which is a really satisfying vision of the near future.

Fifty-some-odd years later (key word: odd), I get to do it again!

Photo by Bill Reaves

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.