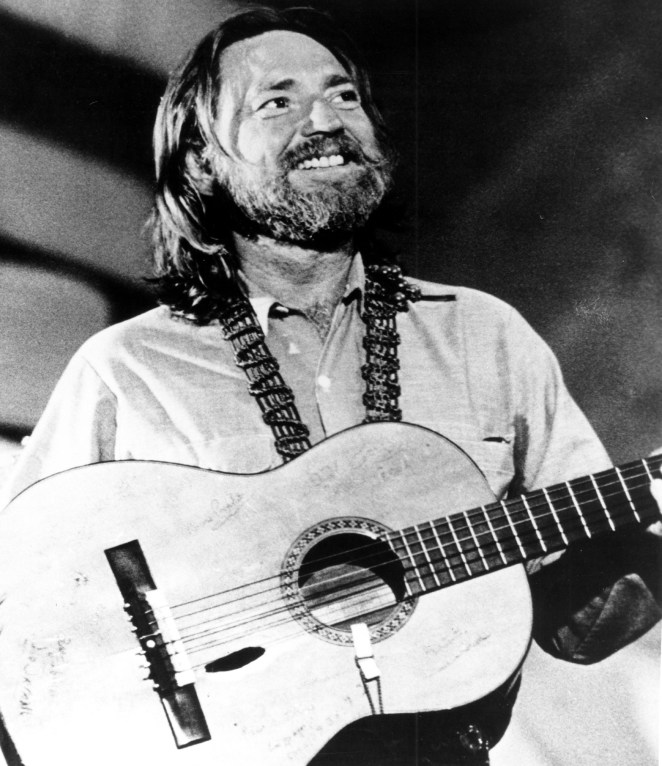

After some tough negotiations, Willie Nelson signed with Columbia Records in 1975 and was given full creative control over his work. Retaining his title of outlaw Nelson went to work on a concept album, inspired by the 1953 Edith Lindeman and Carl Stutz-penned song “Tale of the Red-Headed Stranger,” which he previously played on his show The Western Express as a disc jockey in Fort Worth, Texas.

That year, Autumn Sound Studios had recently opened in Garland, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, and Nelson was offered a free day of recording by sound engineer Phil York, who was trying to promote the new space. Willie took York up on his offer and hit the studio, intent on crafting a bare-bones, stripped-down album, free of overproduction.

Videos by American Songwriter

Nelson’s Underproduced No. 1 Album

With its sparse arrangements, featuring Nelson on acoustic guitar, along with piano played by his sister Bobbie, and complementary harmonica, mandolin, and drums, Red Headed Stranger went to No. 1 on the country charts and peaked at No. 28 on the Billboard Hot 100. The album also earned Nelson his first No. 1 hit, his cover of Fred Rose’s “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain,” which was previously covered by Hank Williams, and later by Elvis Presley and Charley Pride.

“I was gathering songs that I thought told that story,” said Nelson in 2016 of the track that inspired the album and its title. “And I just thought that ‘Blue Eyes’ was the perfect song for that spot. Simple and to the point—beautiful, sad love song. I’ll sing it for the rest of my life. It never gets old.”

[RELATED: 3 Songs Willie Nelson Contributed to The Highwaymen During the Supergroup’s 10-Year Span]

Nelson went beyond the free day of recording and took five days to record Red Headed Stranger, with another day to mix, adding up to $4,000 in studio fees. Additionally, Nelson had received a $60,000 advance from Columbia and used some of the leftover wages to upgrade the band’s equipment and bus.

“Why are you turning in a demo?”

When Nelson finished the album and presented it to the label, it was met with confusion. The label thought Nelson was releasing an album of demos. “‘Ain’t no demo,’ I explained,” said Nelson. “This is the finished product.”

On Nelson’s behalf, Waylon Jennings and Nelson’s manager Neil Reshen went to New York City to play the album for then-Columbia president Bruce Lundvall, who wanted it sent to producer Billy Sherrill in Nashville to touch up the recording with some strings and backing singers.

Regardless of its harsh critiques, Nelson still had creative control and the album was left touched and released as he intended.

“Columbia was not open to the idea of it,” said Nelson on the label pushback. “They wanted a big production—record companies always want a big production. They think that that equals a lot of money. I think they were always hoping to cross over to the pop field in those days. I just wanted it to be a guy and a guitar.”

Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.