Wearing patchwork pants and an easy smile, Bluegrass Hall of Famer Peter Rowan tipped the blue hand-thrown pottery jug inscribed with his name to his lips as if he were taking a large swig of moonshine.

The capacity crowd at the Gleneagle INEC Arena in Killarney, Ireland, roared with laughter and applause. Alison Brown, co-founder of Compass Records and IBMA’s Anna Kline, presented Rowan with the inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award at the Folk in Fusion concert, the kick-off to the Your Roots are Showing conference. YRAS founders commissioned Rowan’s local artisan pottery in commemoration of the honor.

“There has never been and will never be another artist in bluegrass music like Peter Rowan,” Brown said. “He’s one of the most iconic and unique musicians in the history of the music. Peter is simultaneously a traditionalist and an innovator.”

Rowan’s career began as a member of Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys. Like his mentor, Rowan was drawn to innovation.

“Thank you very much,” Rowan said. “I don’t resemble those remarks, except that’s a version of me. This is a treat. We’ll fill (the blue jug) up with something.”

Rowan said Monroe used to stand behind him while he was singing and that Monroe told him to sing like Peter Rowan.

“I didn’t know who Peter Rowan was, but I knew the guy behind me did,” Rowan said. “And he was urging me on.”

I watched the evening unfold, first from a dark, far corner of the arena because music lovers filled every seat. Toward the night’s end, a friend texted and said she found me a chair in the front row. I reached my seat beside Hothouse Flowers singer Liam O’Maonlai, who was gleeful at Rowan’s recognition. He whooped and cheered for the bluegrass artist and other singers while they sang. O’Maonlai stepped behind his keyboard to join Rowan and Americana darling Rhiannon Giddens on stage. Giddens took a mic and led her fellow artists and the audience in a rousing rendition of the church hymn “I’ll Fly Away.” The Folk in Fusion concert ended well past 11 p.m. with an all-sing encore of Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues.”

Regardless of his late night, the 82-year-old Rowan was up and about the next day brimming with stories about Monroe and his decades spent working in bluegrass.

Videos by American Songwriter

1. Can you share your earliest memories of discovering bluegrass?

Rowan: I just found bluegrass to be an organizing factory with all this swirl of sound. I didn’t know what to call it. And I started to realize it was bluegrass.

My mentor was a typewriter repairman called Joe Val, and once I got my license and was 16, I started to pick up on, ‘Okay, this is what this music is.’ I would go pick up Joe after he had done his typewriter and repair work during the day and bring him further out into the country where we were.

We’d go down by the barn and sing, especially in the springtime when things were getting really nice in the country and the days were getting longer. He taught me all the Louvin Brothers- kind of harmonies and things like that. I began to focus that way. And I love the sound of a D-28 guitar, that big sound. That’s when I learned to sing, holding this giant body of wood next to me, feeling the vibration in my body.

2. How has bluegrass changed through the decades?

Vassar Clement, who played fiddle with Bill Monroe, once told me that he had seen a 15-year-old being groomed by Chubby Wise to take over his position in the Bluegrass Boys. That would lead Bill Monroe to recut all his hits. But he said while he was hanging out with Chubby Wise, he saw, at Bill’s request, chubby teaching Jimmy Martin, a young guitar player and singer, to play with a flat pick because everybody in those days played with a thumb pick. A little clue about the bluegrass rhythm: it’s like a bass note strum, right? But if you play with a thumb pick and one finger pick, it’s prum prum prum.

You can play really fast. Some of the bluegrass these days has found like a little up mid-tempo kind of pace. That’s the groove. That’s what everybody’s aiming at. But if you listen to the early bluegrass music like the Stanley Brothers, the tempos are outrageous. They’re just whipping along because there’s no lost motion. There’s no wrist involved. It’s just a thumb and a finger. And that’s the same as on the banjo. So, things change due to techniques and the way people hear things. But if you hear the early Stanley Brothers, it is uncanny because the vocals are floating over the tempo.

That’s another thing that has changed a little bit. Now it’s all like, “Where’s the pocket? The pocket, and you’d have to have the pocket.”

3. What did you learn from Bill Monroe about his approach to rhythm and bluegrass?

When I joined the Bill Monroe Band, I was brought on by Bill Keith, who had played with Bill Monroe. But there’s a little trick right there because, in Bill’s band, you could only have one Bill. So, Bill Keith could not be Bill in Bill’s band. He had to have his middle name as his name, which was Bradford. But he was always introduced on stage as Brad Keith. Brad Keith he’s a fun banjo player.

So, I got to be the kid, and I came on as a guitar player for a tour up around New England. When I first heard Bill Monroe play, I realized that he doesn’t play this sort of what we call the chop or the backbeat. He was much more melodic earlier on. But as he got to where he had to define the beat for everybody, he started hitting that back beat and check.

It’s like the Jamaicans play. They think you’re playing reggae, but you’re not playing reggae. Reggae and bluegrass have the same thing. It’s a much longer beat and very subtle, but there’s no check. It’s the way we hear it. It is so defining of the beat. That was Bill’s defining thing that beat. It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, and you got to learn to play the chop.’ No, the chop is everything. If you get the chop when you come out of the chop, you’ll be in what Bill would call the timing of bluegrass. But to jump into bluegrass with his idea of timing without this rhythmic quality foremost in your approach would be a different thing.

4. Where do you find joy in music?

One of the joys of music is that you make up your mind to give it to other people, which empowers you. We got past the technique. We got into the space. Even in Buddhism, they say happiness begins with thinking of others or not thinking of yourself. It is addictive for musicians and people involved in music. Even just listening to music, you’re not thinking about you anymore.

It makes you feel so happy right then that happiness is contagious to the audience. They suddenly lose themselves, and you’re giving them something to lose themselves in. So, it’s a symbiotic kind of thing about the timing.

5. What keeps you motivated to continue to make music?

I think the answer really is that savage purity is what makes you hear your own music. That’s what makes you believe in it. I’ve heard some Irish music that just absolutely stuns me to my soul. I was just speechless, and emotions that I was not counting on having come up came up. It is really about the songwriting or whoever has created this music, these timeless ballads, and things like that.

Bill Monroe had his solution and how to present his version of it. Onward through the fog, I just had to figure out an approach that would communicate the music to other people for other people that they would feel the music. It’s an endless task. There’s no final moment, which I’m grateful for. If I’ve had longevity, I think that’s part of it, is that I never consider the task done. I always feel inspired by the same, you could say savage purity.

For more information, visit Ireland.com or showingroots.com/.

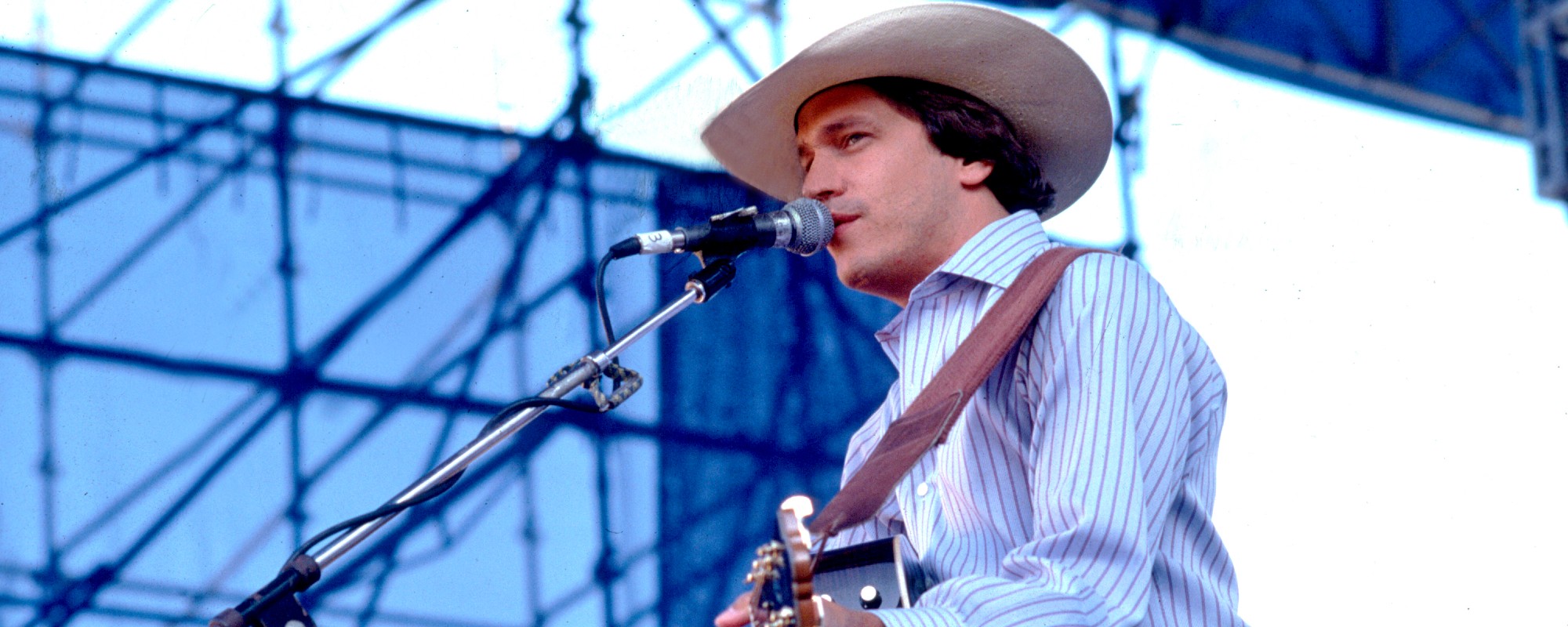

Photo by Colin Gillen

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.