Sometime in 2014, David Ball, co-founding member of Soft Cell, reconnected with Gavin Friday to collaborate on a cover of “Ghost Rider,” the opening title track of Suicide’s eponymous 1977 debut, in celebration of the 70th birthday of founding member Alan Vega. The two hadn’t seen one another since 1985 when Ball produced the second and final album for Friday’s punk band the Virgin Prunes, The Moon Looked Down and Laughed. Years earlier, Friday also appeared on the title track of Ball’s 1983 album In Strict Tempo.

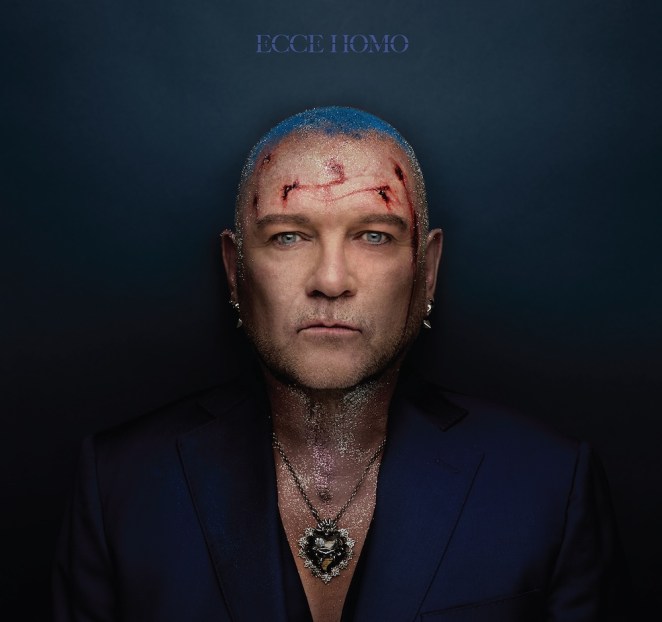

Newly reunited, after their Vega project, Ball started sending fragments of songs to Friday, and the two continued a musical swap for several more years completing a set of tracks that would become Friday’s fifth album, and his first in 13 years, Ecce Homo.

“The strange thing was, it’s 13 years since I brought out an official Gavin Friday album, but I haven’t been working on ‘Ecce Homo’ for that long,” says Friday. “I never walked a straight line in my musical or artistic career, and this [album] started spontaneously.”

Returning to Dublin after recording in London with Ball, Friday wanted to add more orchestration to the songs, charged by his life experiences up until this point, following the losses of friends and family. “I said, ‘Dave, I want to add my cinematic-ness and a lusher sound on top of this contemporary thing,’” says Friday, who added cellos, violas, and other strings.

Friday finished the album by early 2020 then put it on hold for another two years once the pandemic hit and when he experienced more loss, the death of longtime friend, producer Hal Willner.

“A lot of people started dying, which is a dreadful thing,” said Friday. “Hal died very early in the pandemic. My mom died, and then another friend died in Holland [from coronavirus], and it made me switch a few of the lyrics and tones.”

Videos by American Songwriter

His first release since Catholic in 2011, Ecce Homo, meaning “Behold the Man” in Latin, a theme appearing in 15th through 17th-century Christian art, and the words said to be used by Pontius Pilate before the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, is a melting pot of religious examinations and the bruises and healing that come with being human.

A confessional from the past block of years, Ecce Homo follows Friday’s grief after losing his mother—a seamstress who once made the stagewear for the Virgin Prunes—who he and his brothers cared for during her final stages of Alzheimer’s, along with the remnants of his divorce, and finding love again.

The opening “Lovesubzero” cascades into something otherworldly, and “Ecce Homo,” which he calls his “own personal kick in the head and kiss on the cheek to a world gone very wrong,” is accompanied by a tripped-out AI video produced by the film and animation company studio284. Snapping through dystopian scenes around the powers that be, war and destruction, and other religious imagery, the video interrogates the lyrical link between politics and religion—Is there a god living in your old age golden dream / Already crucified in the imagination of men / Resurrecting the lost flesh, for the honey is the money to sell / The silver dollar, the poison pen, I’ll see you, boys, in hell.

“Lady Esquire” imparts some T. Rex vibes with more nostalgic inquests on the pulsing “When the World Was Young,” which Friday wrote when he turned 60. The latter covers reminisces about growing up in Northside Dublin on Cedarwood Road—the same street where a younger Bono, who Friday met at 14, lived. “It’s about meeting my oldest friends who I still know, and us feeling disconnected and connected to the world, having dreams and going for those dreams,” says Friday. “It’s a love song to that friendship.”

Meanwhile, “The Best Boys of Dublin” isn’t a tribute to an old crew of childhood friends but an homage to his beloved dogs Ralph, who passed away in 2023, the day after longtime friend Sinead O’Connor died, and Stan the Man. More tropes around organized religion unravel in “The Church of Love” and “Stations of the Cross,” a love song centered more around letting someone go, and Friday’s closing spoken word sermon “Behold the Man.”

The heart is a dark and vacant room … and hate is the thing that comes too soon, sings Friday on the acoustic “Lamento,” a song spanning a “combination of things,” from the state of nature, financial crises, and injustices.

“Mother Earth itself is not happy,” says Friday of the track. “There’s a devastation to the earth. The big financial crashes didn’t help … the inequality. It’s a load of things.”

He continues “There’s been a lot of love songs written, and you can never better them, but there’s aspects of love that people don’t really talk about that much in songs like ‘Lamento’ and ‘Stations of the Cross.’ I use lyrically religious imagery, but they’re not that religious. I’m not a religious man. I’m spiritual and I have beliefs, but I was brought up as a Catholic in the hardcore old-school way. And I can’t help it. It’s in my f–king DNA.”

Accompanied by a digital EP featuring two remixes and an instrumental version of “Ecce Homo,” along with a deluxe version, the album is a new centerpiece for Friday, who has kept busy predominantly in film throughout the decades, scoring and working on soundtracks throughout the ’90s, including In the Name of the Father in 1993—which also features threes songs co-written with Bono, including “You Made Me the Thief of Your Heart,” performed by O’Connor—along with William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, Mission: Impossible, Basquiat, The Boxer, Moulin Rouge! and more through the present.

Friday and Bono later collaborated on their animated reimagining of the 1936 Sergei Prokofiev classic Peter and the Wolf in 2023, and the song “There’s Nothing to Be Afraid Of.” Also narrated by Friday, the short film is based on original illustrations by Bono.

As a songwriter, composer, actor, and visual artist, Friday’s work has crossed four decades and collaborations with Laurie Anderson, Scott Walker, The Fall, Quincy Jones, and more, along with holding the title of creative director for U2 since the mid-’80s.

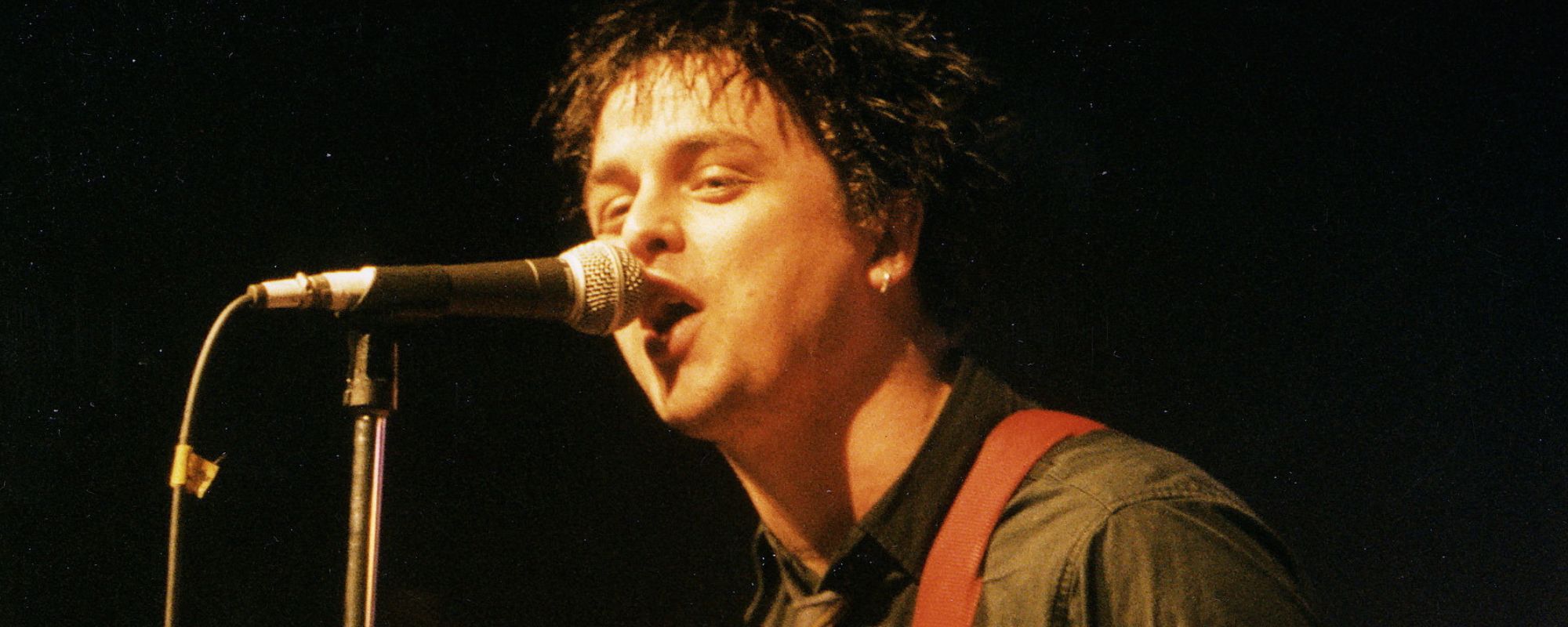

Another project on Friday’s radar has been working on the reissues of Virgin Prunes albums. It was this era of his life, the emergence of punk in Ireland, and everywhere, that catapulted Friday into a different discovery of music and exploring a different solo career with his 1989 debut Each Man Kills the Thing He Loves.

The Virgin Prunes, which also featured U2’s The Edge‘s older brother Dik Evans on guitar, came out of the punk rock era, and Friday fittingly never played an instrument. None of that mattered, he says, since the the philosophy of punk was DIY. “We had to, like, beg, steal and borrow to get anything,” says Friday. “And you didn’t need to play an instrument. You just needed to have an attitude and something to say, then get out there and express yourself. And it gave me and a lot of musicians of my age, including U2 and others, the keys to the car. It was a repressed country at the time, Ireland, and a very poor country.”

At that time, Friday says the band was “making things up” as they went along and recalls the Virgin Prunes being embraced in France, Germany, and Holland, early on as they toured around for years before disbanding in ’86. “We were crazy fuckers,” he says.

“Music gave everyone an ID,” adds Friday. “The Irish are quite poetic. I improvise a lot, and sometimes I get the words to a melody, and then the idea jumps at me. You have that snowflake of an idea and sometimes a song just comes fully formed. But snowflakes melt quickly. You have to catch them.”

Towards the end of the Prunes, Friday started veering into an entirely new direction. “Some of the dreams and the bravado of punk blew itself up as anything that’s that expressive usually does,” he says. “And I started going ‘Fuck punk.’ And I wasn’t really into New Romantics that much. Then I went, ‘Who is Edith Piaf? Oh my God, Jacques Brel.’ And in Germany, it was Kurt Weill. It was like punk rock on another level.”

Friday was enamored by the work of German playwright Bertolt Brecht, who was writing lyrics that were “visceral,” as if John Lydon could have written them. “It was this music, and I said, ‘What is this? It sounds like jazz meets [Richard] Wagner, but it’s commercial and tangible,’ so I became obsessed like a vulture, a cannibal,” recalls Friday. “I just ate up Brel. I didn’t understand the lyrics because it was French, but when music speaks to you, it speaks to you—and then you get translations.”

There was a new artistic awakening for Friday when the Prunes parted ways and he also started painting and seeking out musicians who were classically trained to learn more. Soon after, he began working with film composer Maurice Seezer, who also worked on Friday’s debut, along with its producer Willner, a friend Friday called his “metal guru.”

“He [Willner] was an alchemist,” adds Friday. “And he would go, ‘I’m putting you with Bill Frisell and Marc Ribot at the same time,’ so it was this gentle jazz guy with someone that works with Tom Waits, but these guys were classically trained and could do avant-garde rock. … And they’d play you a record and you’d go ‘Oh my God, I never thought Peggy Lee was this good.’”

All of these musical revelations led Friday onward and into more discoveries. “I was very much a ’70s kid,” he said. “I was the eldest. I had no big brothers to badly influence me. I liked Bowie and T. Rex and Roxy Music. And then you go, ‘Jesus Christ, the Beatles are incredible. Bob Dylan‘s incredible. Leonard Cohen is incredible.’”

Burlesque, the chanson, and decadence were immediate theatrical influences for Friday, along with the music of Waits and Kate Bush. “When I want to write a song, I like making stuff up,” says Friday. “When you listen to their albums, it’s a movie. It’s another world.” Bush’s 1985 album Hounds of Love had a more significant impact on Friday. “It’s phenomenal songwriting and everyone talks about side one, ” he says, “but side two, ‘the Ninth Wave,’ which is about a woman [and fear of] drowning. … That was another learning curve, which I think led me into soundtracks.”

With Ecce Homo and new music in line, Friday insists there’s still more to learn. “I think every year I’m learning and learning and learning,” he says. “I love the idea of learning more, even as you’re older. It’s like going back to school.”

Photos: Barry McCall

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.