Editor’s Note: Keith Stegall provided this guest post for the American Songwriter Membership. Become A Member and get exclusive content, including access to the songwriters behind hit songs by Ed Sheeran, Bonnie Raitt, Morgan Wallen, Guns N’ Roses, and more. You can also enjoy access to special events, song feedback, giveaways, tips, and a community of songwriters and music lovers!

Videos by American Songwriter

“Show me what you got!” Kris Kristofferson told me backstage at a Kristofferson show. I played a couple of songs, which prompted Kristofferson to remark, “Son, you need to get your ass to Nashville and hang out with other writers. They will break you down and make you the best you can be.”

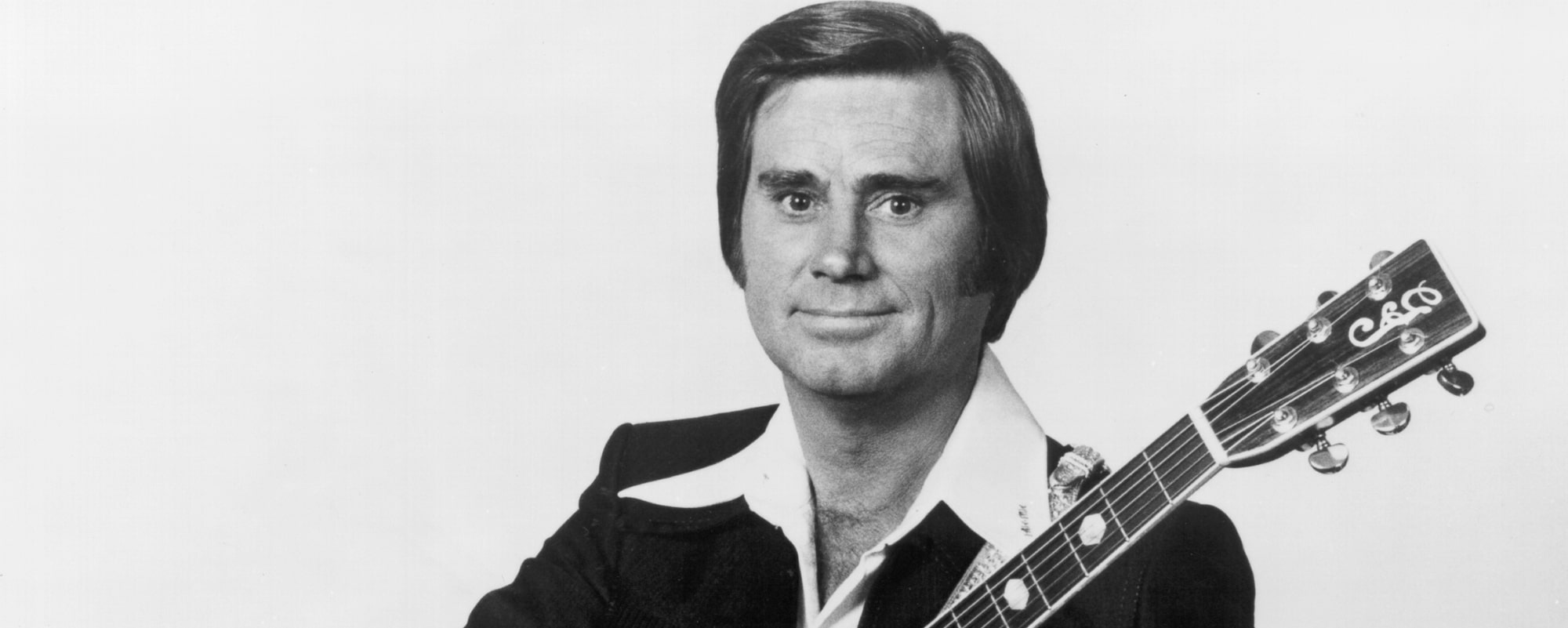

I, Keith Stegall, made the move which led me to a career of writing hits, including “Sexy Eyes” for Dr. Hook, and having cuts by Helen Reddy, The Commodores, Johnny Mathis, Al Jarreau’s “We’re In This Love Together”, “If I Could Make A Living”, recorded by Clay Walker, and “Dallas” and “Don’t Rock The Jukebox” recorded by Alan Jackson. I went on to produce Alan Jackson’s albums. I’ve garnered more than 51 no. 1 hits as a producer and/or songwriter, 40 million airplays as a songwriter, and more than 70 million album sales as a producer. I’ve also won multiple CMA, ACM, and GRAMMY awards.

I still actively produce and write songs, but I recently partnered with The Heartland Network to curate and host High Dollar Hill, where other folks in the music industry and I tell the stories that made the music.

Over this 12-month series with American Songwriter, I plan to break down the art of songwriting, production, and recording in one place. Starting with: “Why Do Songwriters Write?”

Keith Stegall: Why Do Songwriters Write?

When American Songwriter asked me to collaborate on a 12-month series about songwriting and music production, I had to start at the beginning. So, here we go:

Why do songwriters write?

The way I perceive it is that some writers write songs because it’s cathartic. There are also writers fortunate enough to write to be cathartic and commercial. While writing for catharsis is great, the commercial piece of the business is what most Nashville writers want.

I write because I have to. I simply can’t not write. It’s as much therapy as it is a calling.

There are incredible writers like Lori McKenna who seem to encompass the catharsis and the commerciality; there’s a gift in that. I think the same thing about Kris Kristofferson. He was able to do that.

In my experience, Nashville is wired to look for the commerciality in a writer. Still, there are those among us who write these amazing songs – which in some way are commercial, but in another, completely different way, they’re very literary: Alan Shamblin (I Can’t Make You Love Me” and “The House that built me”} does that and so does Mike Reid (“Where The Blacktop Ends, “Walk on Faith”) do that. I know I’m leaving many writers out, but those are two great examples.

Figure Out What Kind of Songwriter You Want To Be

If you want to grow as a professional writer, the first thing I’d recommend is figuring out what kind of writer you want to be and studying those who have gone before you in that vein.

Find a writer that you can identify with. Usually, someone inspired you, or you came across a song that moved you, and you noticed the writers, or the writer, in the liner notes. Then, start looking for the other songs that the writer has written. That’s where you find real common threads running through how they write their songs.

I think I was no different than anybody who listens to the radio. In the era I grew up in, though, it was a very album-oriented world. I would hear one song on the radio by somebody, and I would go try to find out more about them. Usually, there was an album with liner notes in the credits. That was gold to me.

Once you find what moves you, keep studying. Get your hands on a music book and deep dive into the lyrics. I would study how word efficiency works because that’s the key to being a great writer.

Word Efficiency Is Key

For commerciality, pay attention to the Top 10 on the radio and streaming, and you’ll begin to tell what a great song is and songs crafted for a commercial appeal.

And let me be clear – there’s no slight on either style. For example, “Fancy Like” and “The Dance” are both great songs; they’re just different animals that fall solidly under the umbrella of professional songwriting.

I’ll share a bit of my early journey for some examples.

After I met Kris Kristofferson, I discovered Dan Fogelberg. Once I discovered Fogelberg, I thought, “I’ve really gotta get to Nashville. I gotta find who’s working with Dan Fogelberg.”

That man was Norbert Putnam.

Now, before I moved to Nashville, I was working on the West Coast with April/Blackwood Music. At the same time, publishers were beginning to tell me I was good, but “You’re not quite there yet.” April/Blackwood had just opened an office in Nashville, so I made the move.

My contact at the publishing company was Judy Harris. I played her a couple of songs, and she hired me as their “tape copy boy” with a writer’s contract attached to it. I think for 200 bucks a week, so that’s kind of where it started for me.

I think it was my second year in Nashville, and I’d had my second pop hit after Dr. Hook’s “Sexy Eyes,” with a song called “We’re In This Love Together” by a guy named Al Jarreau. I thought those cuts might be kind of a liability because Nashville was a country town, and was the guy getting pop hits. I thought I’d be looked at a little bit differently.

Keith Stegall Worked for $200 a Week

But then something incredible happened.

Norbert Putnam sought me out. Yeah. That Norbert Putnam.

The phone rang one evening at the publishing house, and I answered it. This voice said, “Hi, this is Norbert Putnam. Can I speak with Keith?”

I thought, “Somebody’s playing a trick on me.” Once I figured out the call was legit, we talked, and he invited me to Bennett House to hang out. All of a sudden, I’m there hanging out with my songwriting heroes.

In my experience, if you show up with your best songs and ideas, your people will find you. It may not happen in your exact timeframe, but it will if you keep showing up.

That happened again when Gary Overton introduced me to Alan Jackson. We were just casual friends for quite a while, and we were all kind of hanging out at Glen Campbell Music Group, which Marty Gamblin ran. None of us was setting the world on fire yet, so we needed a place to hang out.

Alan Jackson Changed Keith Stegall’s Life

We always said we were like “a few rats on a log, just floating along.” A group of us would hang out and play demos for Alan. He would ask me questions like, “How’d you get that particular sound?” or “How’d you get those vocals?” At the time, I’d produced Randy Travis’s first live album, called Randy Ray: Live at The Nashville Palace, before he got his deal with Warner. (I was actually an artist at the same time, and my producer was a guy named Kyle Lenning.)

Alan finally just asked me, “Will you record some demos with me?” That’s how Alan and I started working together.

I wrote “Don’t Rock the Jukebox” with Alan and Roger Murrah. Alan and I wrote “Dallas,” and I wrote another song called “Love’s Got a Hold On You” with Carson Chamberlain.

In those early days before Alan got completely wrapped up in touring, we wrote a lot together – some things are actually still in the can – but that just happened because we spent time together and enjoyed our writing process.

Practice Makes Better Writing

As with anything, you get better with practice. If you co-write, bring great ideas and be ok knowing you’re not necessarily gonna write a hit in that first session. Learn from each write and take advice from the old guys who have done this for a while. They tend to have really good advice. I think of it as a classic master/apprentice relationship.

I was fortunate to have Roger Murrah take me under his wing. He explained to me, “Why you do this, or why don’t you do that?” and just how important word efficiency is. He encouraged me to have the best command of the English language I could in order to move people with a lyric. Our writing relationship was one of those “apprentice learning from the master” types.

For example, Roger taught me that you can change the direction of a lyric by changing one small word. Maybe you change a “but” to “or” or to “and.” Those are details you don’t pay attention to as you first start to write, but as you grow, you start paying attention because they can shift the dynamic in a song.

The best thing Roger taught me was that listening is much more important than talking. That’s where you learn the good stuff.

Listening Is More Important Than Talking

So get out there. Find the kind of writer you want to be, study the masters, and hone your craft through disciplined practice. Pay attention to when your ideas flow and write them down (I love the Notes app on my phone), and show up prepared for co-writes.

Photo by Larry Busacca/Getty Images for Songwriters Hall Of Fame

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.