John Lydon has said that his “body and mind is the Sex Pistols but his heart and soul is PiL.”

Videos by American Songwriter

The godfather of British punk, Lydon — Johnny Rotten in the Pistols days — snarled his way through British punk and had something more to say through his artsy alt-rock brigade of Public Image Ltd (PiL) by the late ’70s and through the band’s present day.

Never uniform in his approach, his lyrics have been fastened by safety pins of quick wit, sarcasm, gripes, and the uglier ends of real life and death, along with his musical penchants for experimenting with dub and reggae, Middle Eastern, electronica, and unconventional sounds. Lydon has produced one of the most idiosyncratic collections of narratives throughout his nearly 50-year career.

Born John Joseph Lydon in London, England on January 31, 1956, by the age of 19, Lydon joined the Sex Pistols and helped write most of the band’s compact catalog, from the anti-establishment anthem “Anarchy in the U.K.,” the disenchanted “God Save the Queen,” and sardonic drabness of a communist-era East Berlin on “Holidays in the Sun.”

[RELATED: The ‘Novel’ Concept Behind the Band Name Public Image Ltd (PiL)]

Shortly after The Sex Pistols’ demise in January 1978, Lydon formed Public Image Ltd — a name pulled from Scottish writer Muriel Spark’s 1968 novel, The Public Image, the story of an actress obsessed with her appearance.

PiL released its debut, Public Image: First Issue, followed up with The Metal Box in 1979, The Flowers of Romance in 1981, and eight more albums through their 2023 release End of the World. The latter album features one of Lydon’s most sentimental songs, “Hawaii,” which he wrote for his late wife of nearly 45 years, Nora Forster, who died on April 6, 2023, at 80 after a lengthy battle with Alzheimer’s disease. The band also performed the track during the 67th annual Eurovision Song Contest, representing Ireland.

In between his years with PiL, Lydon released his sole solo album, Psycho’s Path, in 1997 and his fourth book, I Could Be Wrong, I Could Be Right, in 2021.

Lydon chatted with American Songwriter about how improvisation and “organized confusion” help him write, and why he’s still “difficult to work with.”

American Songwriter: Are you still the same songwriter you were from the early days with the Sex Pistols through PiL and now?

John Lydon: As long as there are human beings out there getting on to whatever human beings get on to, how can I ever run out of material?

AS: Do these human “conditions” make it easier, or more challenging to write?

JL: I try not to force it — ever. I’ve seen songwriters in other bands that will allocate a specific time and they’ll sit down at their desk with their pen and paper. That’s not songwriting. That’s doodling. And sometimes — and it happens an awful lot in studio — I’ll improvise on the spot, then I’ll quickly run to the pen and paper and try to remember what it was I just did. So it’s like “Wow, my big bad self just impressed me. It just flew off the top of my head.” And it’d be the completely right space and time for it to be there. I think that happens because I never stopped thinking.

I like the constant juggling about from one subject to another. I like that. It’s a chaotic thing but in an odd way. It’s madly organized and if it’s the right moment and the right time, it could just take somebody dropping a guitar in the corner of a room. It’s just that crescendo of notes and bang my brain is on it.

I’m pontificating genius or anything like it. My words have to reflect exactly how it is I view life, and how I think. So there you go—organized confusion.

AS: Is that the same as organized chaos?

JL: Well-organized chaos is all well and fine (laughs), but it just delays your work on time.

AS: You’re also a visual person, and art informs a lot of what you do. Does the visual ever trickle into songs? (A visual artist for years, Lydon painted a number of covers for his solo material and PiL albums, including the cover art for Public Image Ltd’s 2023 release End of the World.)

JL: I love electric blues and pale greens. I love bright colors.

When I was really seriously ill when I was a child, I could read and write before that, but I lost my memory for a few years after. (At the age of 7, Lydon contracted spinal meningitis and lost much of his memory once he recovered.) I would go off to school and the local library got me really interested in painting and taught me lessons that have stuck with me for life, that a painting doesn’t need to be centered and divided into appropriate squares and be geographically supreme or architectural. No! Go with what colors you love and daub away to your heart’s content.

That’s more or less my approach to music, too. Use what’s available and really enjoy doing it. Formats drive me crazy because they’re so damn limited. In a solo project, I used toilet and kitchen [paper towel] cardboard rolls, because I wanted the Chilean pipe vibe. I found I could get it with the cardboard kitchen rolls, and I remember one review, they were slagging me off for not being a serious musician. This is the world I live in. They were so pompous.

It just shows that they don’t love the actual sounds. They love the structure and the mathematical principles behind it, and that’s a rather pointless, soulless, lifeless existence for me.

AS: Everything does seem boxed into some category or another. If you’re in pop, and you want to do something punk or metal, it doesn’t fit.

JL: According to who? Who wrote this manifesto? Record labels are responsible to an enormous degree because they’ve got an eye on “How are we going to promote this? What radio airplay are we going for?” This is all the language of the alien species to me. And this is why I’ve earned over the years the incredibly honorary title of “difficult to work with.”

AS: Yes, I’ve heard this title of yours. You seem lovely. I don’t know what they’re talking about.

JL: Every time I’ve done anything, there’s been a whole host of bands that come out a year later with something similar, but by then I’ll have moved on to another way of approaching something. I’m not laying tiles in a kitchen to last 50 years.

AS: Since you’re in this constant shape-shifting state, how do older songs, whether it’s the Pistols or PiL, resonate with you now?

JL: It’s the same as looking back on old drawings or paintings. They weren’t precisely right for that time, so I approached them that way. I never look back and go, “Oh, we need to re-edit that.” No, no, no. I said them because that was as accurate as I could possibly be, at the moment.

With the death of my mother, who died horribly painfully from cancer, I put together “Death Disco” [off PiL’s Metal Box, 1979] for her, a song of screaming agony. And my father died fairly recently. Then there’s the endless terrain of stupid rock deaths, as I call them, and friends killing themselves with heroin — the drug that avoids self-pity. So you watch all this, and people just don’t seem to want to learn.

So yes, of course, I’m difficult to work with. Under those constraints. I would say I’m fucking impossible to work with.

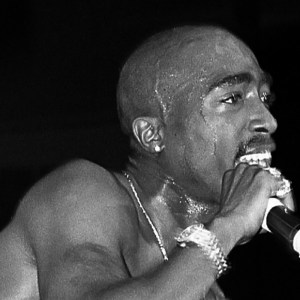

Photo by Gus Stewart/Redferns