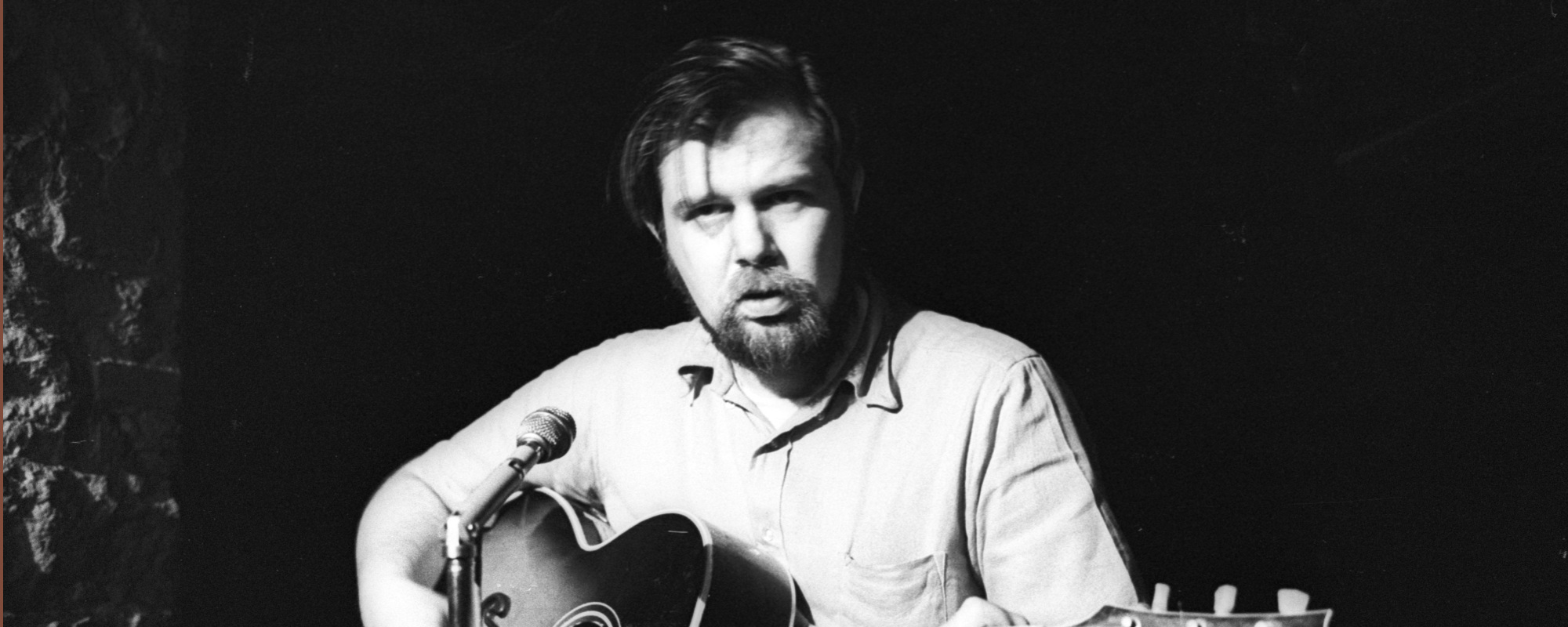

On March 7, 1944, Townes Van Zandt entered this world for what would be a too-short journey across the world, sharing his melancholy and profound songs, each their own masterclass lesson in songwriting. Van Zandt was somewhat of an enigma, born a wealthy descendant of 19th-century Texas leaders and slated to become a straight-and-narrow lawyer or senator.

Videos by American Songwriter

Instead, Van Zandt opted for a life on the road. He struggled with manic depression and alcoholism, and the insulin shock therapy for the former ailment zapped much of his long-term memory. By 1966, following the death of his father, Van Zandt gave up his (or, perhaps more appropriately, his family’s) dreams of a “normal” life and began playing music in bars across the western United States and beyond.

In the end, Van Zandt never reached the same global acclaim as, say, Bob Dylan or Woody Guthrie. Nevertheless, he is beloved in folk circles and considered a massive influence to artists who came after him. In honor of what would have been Van Zandt’s 81st birthday, we’re taking a look at a small sampling of some of his best works.

“Pancho and Lefty”

Although we often associate “Pancho and Lefty” with Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard or Emmylou Harris, Townes Van Zandt is the original songwriter. This is perhaps one of the best examples of his masterclass songwriting: a true folk ballad that reminds the listener that not everything is as it seems. The song follows Pancho, the Mexican bandit, and Lefty, a man from the States who left his comfortable home to pursue a more rugged life. In the end, Pancho dies, likely betrayed by Lefty, who mysteriously evaded capture by fleeing back to the States. The day they laid poor Pancho low, Lefty split for Ohio. Where he got the bread to go, there ain’t nobody knows.

At first glance, one might assume the song is a lament for Pancho. But Van Zandt reminds the listener that Lefty’s fate was arguably worse. The poets tell how Pancho fell, and Lefty’s living in cheap motels. Pancho might have died in the desert, but he died a folk legend. Lefty was left to grow old, each extra year reminding him of how he turned his back on his friends. Pancho needs your prayers, it’s true, but save a few for Lefty, too.

“For the Sake of the Song”

One of Townes Van Zandt’s most distinct characteristics as a songwriter was his ability to capture the essence of bittersweetness. His songs were full of heartache, melancholy, and a healthy dose of aloofness. Yet, there was an empathy there that offered some sort of small silver lining to cut through the darkness. “For the Sake of the Song” perfectly blends love and dismissal. Throughout the sprawling ballad, the narrator tries to reconcile his relationship with an unknown woman. Why does she sing her sad songs for me? He begins. I’m not the one to tenderly bring her soft sympathy.

The song seems to be Van Zandt wrestling with two realities: he cares for the person of which he speaks, but he refuses to give up his life for her. Moreover, he doesn’t really believe his presence would make that much of a difference in the first place. Does she really believe that some word of mine could relieve all her pain? He brings each verse back to the idea that maybe this relationship’s problems have nothing to do with him in the first place. Maybe she just has to sing for the sake of the song, and who do I think that I am to decide that she’s wrong?

“Nothin’”

Substance abuse was a common fixture in Townes Van Zandt’s life. From alcohol to h***** to c******, the singer-songwriter found himself in and out of rehab throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. He captured this hard and lonesome existence in countless songs, but one of the most poignant was “Nothin.’” The song seems to be the two sides of Van Zandt at war with one another: the addict and the man who wished to be free of his sickness. He seems to push away an unknown woman in the first verse: Hey mama, when you leave, don’t leave a thing behind. I don’t want nothin’, I can’t use nothin’. Take care into the hall, and if you see my friends, tell them I’m fine, not using nothin.’”

Toward the end of the song, Van Zandt reflects on the never-ending cycle of temptation that life creates. Being born is going blind and buying down a thousand times to echoes strung on pure temptation. He leaves the listener with a mantra: Sorrow and solitude, these are the precious things and the only words that are worth remembering. As if to say: the things you’re running from by getting high are things to embrace, not reject or hide away from.

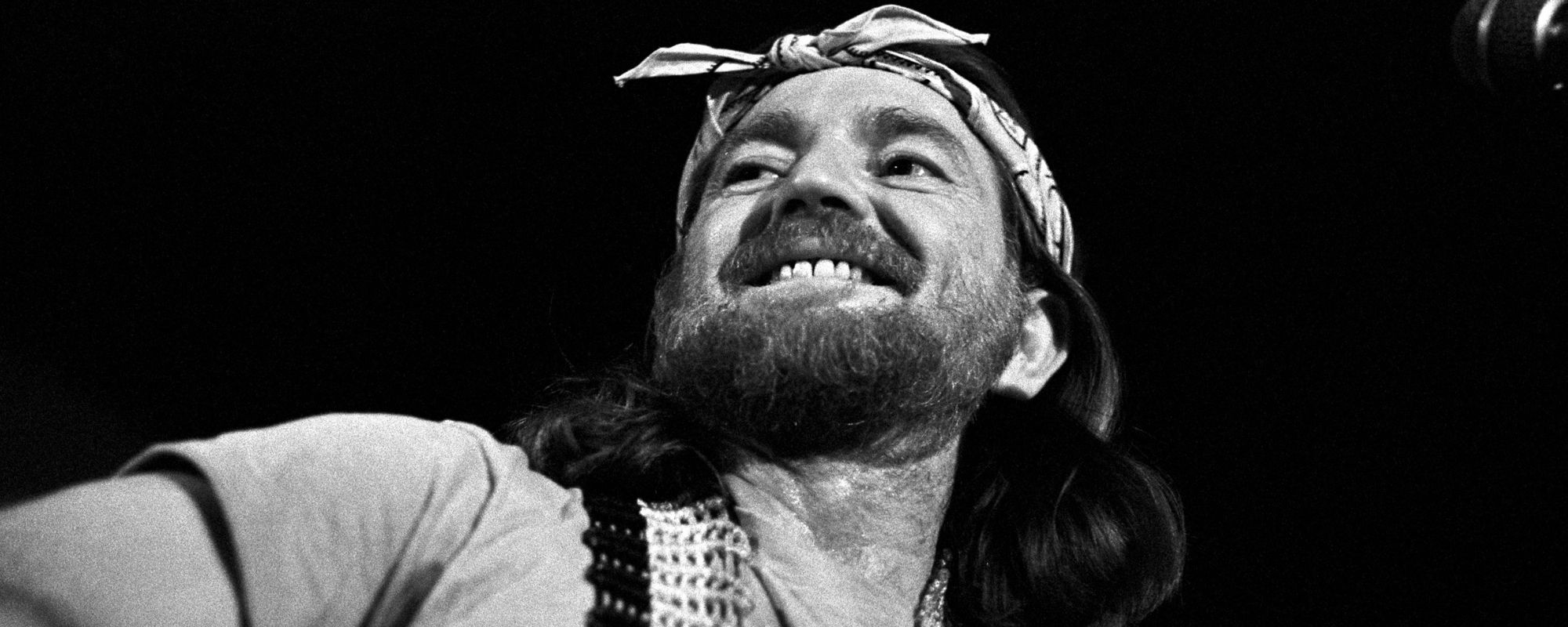

Photo by Tom Hill/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.