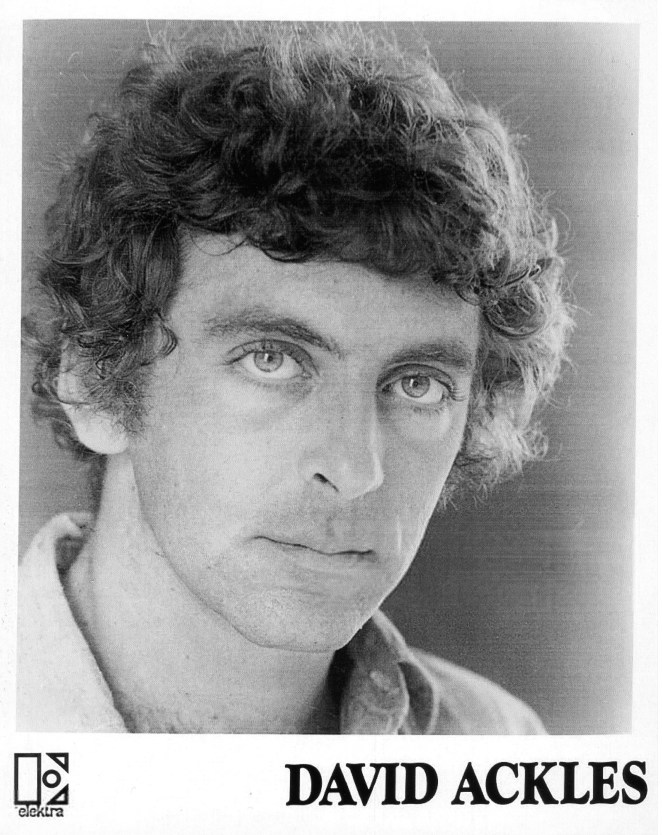

Do you know David Ackles? In 1972, his album, American Gothic, was declared by the press to be the “Sgt. Pepper of Folk” and “one of the greatest records ever made.” His admirers included Elvis Costello, Elton John, Greg Ginn (Black Flag), Phil Collins, and more.

Videos by American Songwriter

So, what happened to David Ackles? Writer and musician Mark Brend’s new book Down River, which will be out on 8/15 and is available for pre-order on Amazon and B&N, is a search for an artist who got lost. And the author is treating us to a sneak peek into this fascinating story. It’s an illuminating study of a forgotten enigma of the 1960s and 70s, and of mythmaking in the popular music industry.

First, a little background to catch you up, followed by an excerpt from the book:

“When David Ackles turned thirty in February 1967, he looked set for a varied, low-key creative life of teaching, provincial theatre, a little writing, and composing for the stage. There was little to suggest that before the year was out, he would be recording his debut album for the hippest of US record labels. Everything changed when Ackles bumped into an old college friend, David Anderle, over the summer. Anderle was a music industry mover and shaker. He’d already signed Frank Zappa and The Mothers Of Invention to MGM, managed Van Dyke Parks, and ran The Beach Boys’ Brother label. Now Anderle was working at Elektra, and after Ackles played him some songs he’d been working on, Anderle signed him. Initially, as a songwriter only. But Elektra’s founder, Jac Holzman, had other ideas.”

David Ackles: Last time I’d seen him was several years before in a paintspattered outfit, leaving a set—he was a set designer at USC. […] So, I played the song for him […] and he liked it a lot. He said, ‘Yeah. I really like that, and I want you to write some more.’ And I said, ‘Why?’ And that’s when he divulged the truth: ‘I am with Elektra!’ So I immediately ran home and whipped out twenty songs and came back, and then he introduced me to Russ [Miller], who was at the house that day. I played the songs for both of them, and that’s when they signed me.

In September 1968, on his first promotional visit to the UK as an Elektra artist, Ackles explained that he’d written some songs and made some demo recordings to show how they went, which prompted Elektra to suggest he record them himself. He’d said much the same thing in a Los Angeles Times interview a month earlier. And when I spoke to him thirty years later, he had this to say:

David Ackles: Did I always hope and plan to be a songwriter? Yes, from earliest childhood, that was one of my ambitions. I had others, of course, but songwriting was the dominant goal. But a recording artist? Not on your life! My intention was to have lots of other, much better singers record my songs. Alas, it was not to be. I believe the truth is that Jac Holzman couldn’t interest any other singers on his label in recording my stuff, so [he] was forced into offering that chance to me. I had an album released before I had ever performed solo in public.

Janice Vogel Ackles: I remember David telling me that once he submitted the material, he didn’t think he was going to record it. He thought that they were going to farm it out to other people, so it came as a big surprise to him.

David Anderle: I believe Russ Miller and I took him into the studio and cut some demos with him. […] We played the demos for Jac, and Jac certainly gave the okay to proceed [with the album].

Jac Holzman: Ackles was very sweet, considerate—the kind of guy who wouldn’t swat a mosquito. A gentle soul, an extremely gentle soul. Introspective. He lived a lot within himself and within his music. Ackles came to us through David Anderle, he had been kicking around and was a high school buddy of Anderle’s. And Anderle brought him to Russ Miller, who was an A&R guy who was on the outside, in the beginning, didn’t do a lot of production. They produced the first Ackles album together.

Holzman thought that Miller had good taste and was sensitive to acoustic music. Which, as piano and vocal renditions, is what Ackles’s music was when Miller first encountered it. Miller immediately engaged with the songs and recorded demos with Ackles, which he played to Holzman. Miller’s enthusiasm rubbed off on Holzman, who loved the demos for their gentle introspection. He was intrigued by the theatrical bent in the writing and thought the songs probably wouldn’t sell. And, crucially, that Ackles should sing them himself.

Miller himself added some detail to the story. He’s quoted in Elektra’s UK newsletter in 1968, just before Ackles’s promotional visit to Europe, that it took three visits to persuade Ackles to sing his own songs.

Though aspects of the journey remain elusive, the destination isn’t in dispute. Ackles found himself recording an album for Elektra, produced by Anderle and Miller. If Anderle was an interesting character, his coproducer, Miller, something of a spiritual seeker, could have stepped out of one of Ackles’s songs. As a youth, he had been a tent evangelist and singer, and then later a recording artist and producer. After leaving the music business, he became a motivational speaker and was then ordained as a Religious Science minister.

In 1969, Miller was appointed Elektra vice president and head of the West Coast division. In 1967, though, he was running Elektra’s affiliated publishing company, Paradox Music Group, to which Ackles signed on November 10, 1967. The transition from staff songwriter to debut recording artist must have happened within a few weeks. There are American Federation Of Musicians records showing that Ackles was recording in January 1968, so almost certainly the decision to do so would have been made before the end of the previous year.

When Ackles turned thirty in February 1967, he most likely would have had no thought of signing a record deal before the year was out. Yet here he was, recording his debut album under the watchful eye of a paradigm of LA cool and a one-time youth evangelist. On the surface, it seemed like an unimaginable turn of events. But that wasn’t quite the case.

In 1967, Ackles didn’t appear quite as unusual as he does now. By the time he recorded his third album in 1972, he’d carved out a musical niche entirely his own. And, looking back, you can see in his first album clear hints of that mature style. The theatrical, the hymnal. In 1967, though, with his style still emerging, it was possible to place him alongside a new generation of literate, intelligent artists. Leonard Cohen. Labelmates Fred Neil, Tim Buckley, Judy Collins, Tom Paxton, and Tom Rush. Some even played piano, not guitar. Randy Newman, Laura Nyro, Harry Nilsson. Newman, Nyro, Nilsson, and Cohen all wrote songs that demonstrated an awareness of forms beyond the normal rock idioms of the time. As did Ackles.

Indeed, reviews of Ackles’s debut album often mentioned one or more of those artists as a comparator to help orient the reader. It was not a scene, hardly even a trend, but there was something happening, and Ackles seemed to be skirting the fringes of it. But he didn’t really fit.

Buckley, Neil, Newman, Nyro, Nilsson, Paxton, and Rush had come up through versions of one of the established routes into the music business. Ackles hadn’t. As he put it, ‘I came in the back way.’

Fred Neil had been writing songs and making obscure singles since the late 1950s. Randy Newman had been writing songs for other artists since 1961 and had recorded a flop single himself in 1962. The prodigiously gifted Laura Nyro had landed a record deal and recorded her debut album while still a teenager. So had Tim Buckley. By 1967, Tom Rush had been playing the folk circuit for years and was already five albums into his career. Tom Paxton, the same age as Ackles, was already hanging around the Greenwich Village folk clubs when Ackles was in New York trying to break into theatre. He had released four albums by 1967.

Harry Nilsson started out singing songwriting demos and writing for other artists. Only Leonard Cohen had no previous music industry form, but his provenance as a poet and experimental novelist gave him countercultural credentials in a way that Ackles’s history of acting, church theatre productions, and writing for television didn’t. It’s as if, launching himself on a different trajectory some time earlier, his idiosyncratic journey intersected with a well-travelled path in 1967. For a while, it looked as if his career might shape up in similar ways to some of his contemporaries—that he might continue that well-worn path. But the intersection was an accident. The further Ackles went on his journey, the harder it became to relate him to anyone else and fit him into what was happening.

If it’s possible to see how people imagined Ackles might find a niche back then, it’s possible, too, to see how events played out in his favour. Ackles and Anderle were old friends. And Anderle was working for probably the only label with the vision to see the potential in Ackles, and the nerve to sign him. And this at a time when the music business was booming in Ackles’s hometown. Though that’s not to imply Elektra’s signing policy was profligate.

Holzman, speaking about the company’s expansion, said, “One song in 1,000 tapes is eventually recorded.” There was happenstance and opportunism in Ackles’s arrival at Elektra, but it wasn’t just being in the right place at the right time. Anderle’s association with Van Dyke Parks and Brian Wilson marked him out as a man with an ear for songwriters pushing at the established boundaries of pop. Holzman, a born risk-taking entrepreneur, combined hard-nosed business acumen with a true love and deep knowledge of music.

Under his guiding hand, Elektra was becoming a rock label, but it didn’t start out as one. Holzman was always open to other forms of music. Miller was also a seasoned music industry insider with—as his career demonstrates—an unconventional streak. These were the men—successful, powerful, and unusual, always looking for the next thing, not just bean counters—who saw something special in Ackles and his strange songs. Songs of originality and daring, and yet songs, too, that you could have just about imagined then as hits. Songs that almost were hits, in some cases.

This excerpt was originally shared with our American Songwriter Membership. For exclusive content, including access to the songwriters behind hits by Ed Sheeran, Bonnie Raitt, Bobby Bare, Guns N’ Roses, and more—plus events, giveaways, tips, and a community of songwriters and music lovers, become a member.

Photo via Elektra

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.