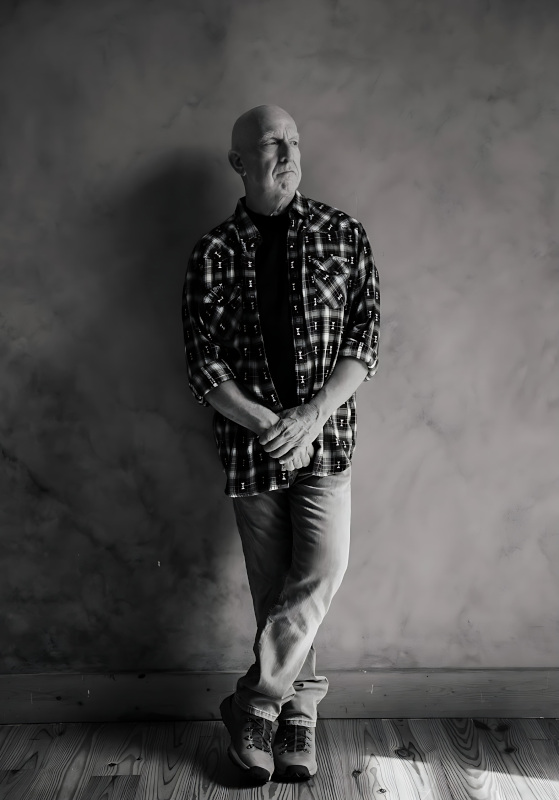

Bernie Leadon can pinpoint when coolness eluded him, as well as when it suddenly returned.

Videos by American Songwriter

“I know the exact moment I stopped being cool is when my son was born,” Leadon says with a laugh. “He couldn’t tell me right away that I was no longer cool. But as soon as he could talk, he explained it to me. And he wasn’t wrong. But now he’s 45, and he thinks I’m cool again.”

Leadon titled his new solo album, Too Late to Be Cool, after one of the excellent songs he wrote and recorded for the project. Considering this LP comes some 21 years after his last solo album, and that it’s only the third such release of his career, some might indeed associate the artist with tardiness.

Of all the former Eagles members, Leadon has always seemed the least interested in stepping back into the musical limelight that once shone so brightly on him during his time with that highly successful band. As it turns out, Leadon’s reunion with his former band a little more than a decade ago actually spurred him to get back into the singer-songwriter game.

So here he is, in 2025, sounding fresh and energized with an album that only occasionally hints at the country rock with which he’s most associated. Too Late to Be Cool finds him and an ace backing band of Nashville musicians taking on everything from soul balladry to fiery rock, from smoky blues to supper-club jazz. As Leadon explained to American Songwriter in a wide-ranging interview, the variety doesn’t surprise him, even if it might sneak up on his audience.

“It’s what I ended up writing, and it’s what (producer) Glyn (Johns) and I chose out of the pile of songs I had,” he says. “The acoustic jazz thing is probably the most far afield for me, partly because jazz, for me, is a little more complex. As for the acoustic blues stuff, I’m an old folkie at heart. Before even country rock, it was folk, and then bluegrass, and then I strapped on a Telecaster.

“I’m happy to report that over 50 years, I did grow and evolve a little bit, which is nice,” Leadon says with a wink.

Bernie’s Journey

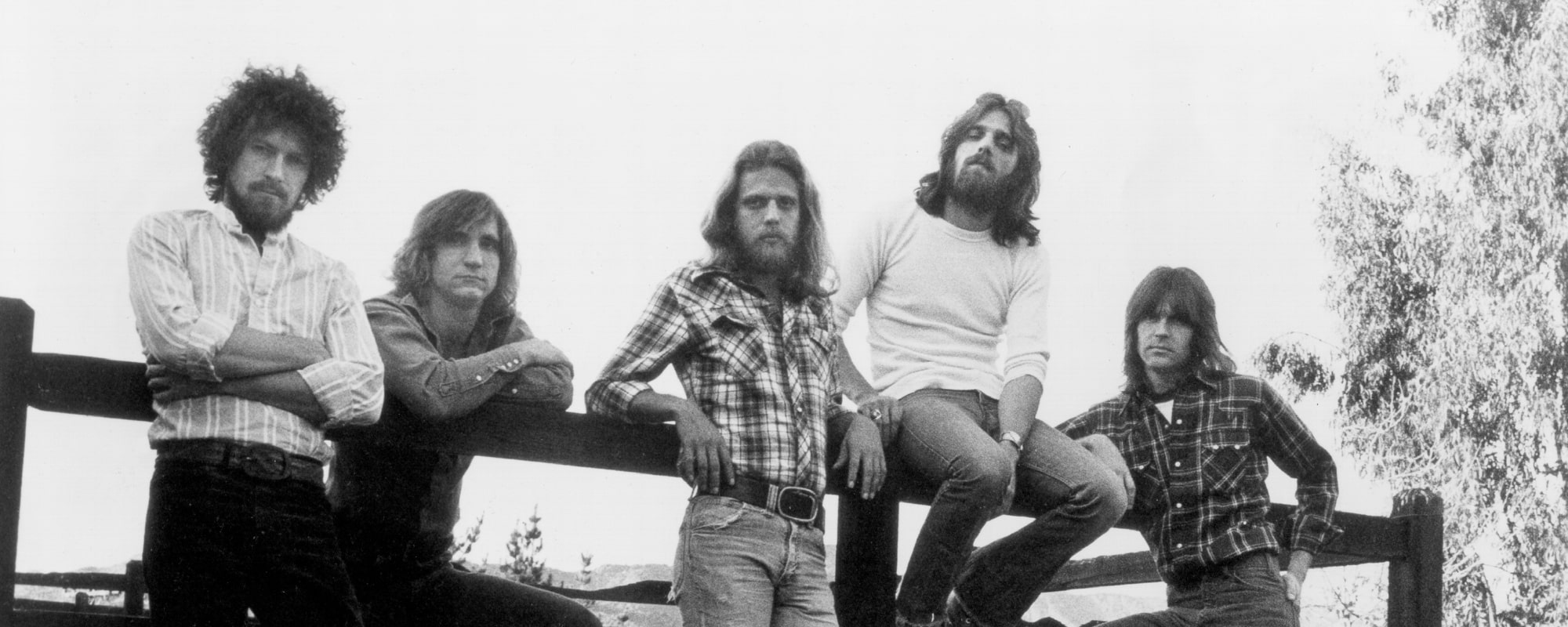

While Leadon might not have stepped out into the forefront much after leaving the Eagles in 1975, he stayed plenty active, adding his instrumental expertise to albums from a wide variety of high-profile artists. In 2013, he returned for The History of The Eagles tour. That started him on the road to recording on his own again.

“I went on the road with the Eagles from 2013 through 2015 and played a lot,” Leadon recalls. “We did 175 shows around the world, a lot of rehearsing. So my chops were really good. I was really enjoying it. The big thing that changed was that I decided to be more conscientious about songwriting. I wanted to write more, so I started focusing on it.”

“It took about nine years to get to the point where Glyn Johns said, ‘Hey, why don’t I come over and see what you’ve got?’ By then, I had about 100 songs I liked. I showed Glyn maybe 30. We pared it down to record 15 and pared that down to 11 for the album. We had a lot to choose from, which was really cool.”

Leadon might have delivered an album sooner. But since he had amassed a large amount of analog recording equipment over the years, he decided to build his own studio from the ground up to house it all. Thanks to Johns’ firm guidance, whose experience with Leadon dates back to producing the first three Eagles’ albums, the actual recording process went quite smoothly.

“Glyn Johns is fearless about making decisions as we go,” Leadon says. “Like you do a vocal for him and ask, ‘Can we do another one?’ And he’ll just put it in record to record over the one you just did. At first, you think, wait, I might want that one. He’ll just say, ‘I thought you were going to sing it better. Let’s go.’ That’s much more efficient. We did all the recording in 3 ½ weeks, and it took about four days to mix it. Done.”

Leadon also credited the studio musicians (bassist Glenn Worf, keyboardist Tony Harrell, and drummer Greg Morrow) for coming ready to deliver the goods. An old-fashioned recording experience, with the instrumentalists all in the same room playing off each other and minimal digital patching, contributed heavily to the finished product as well.

“You’re looking at each other, and you can hear each other,” Leadon says. “One guy plays something, and somebody else reacts to it. Organically, you react to one another, and it evolves. We got a lot of early takes. That’s key, because it has the energy and freshness to it.”

The Cool Factor

The recording process lent Too Late to Be Cool a winning old-school feel. But Leadon’s songs are what truly elevate the album. To keep his eye on the ball, he followed a routine more akin to other forms of creating than songwriting.

“Article writers, short story writers, they all say they have to be disciplined about it,” he explains. “Some like to write in the morning, some in the afternoon, some in the evening. But they typically have a disciplined schedule where they write every day for two hours or something. For me, it’s when I first get up, have coffee, and grab the guitar.

“When I first pick it up, my hands will just start doing something sometimes, almost like nervous energy. And I’ll say, ‘Wait, what was that? That was cool.’ And then I’ll develop it. I just got one of those the other morning. I also have a book with lyrical ideas and titles. Sometimes when I get a riff or musical idea, I’ll go to those and see what jumps out at me.”

There’s a philosophical bent to songs like “Zero Sum Game” and “Fathom” that hints at lessons learned over many years. But Leadon also gets feisty at times, as on the thunderous “Just a Little.” “I was saying ‘Just a Little’ like severe understatement, right?” he says. “Just the idea that everybody is frustrated about something. In the verses, I tried to think of every non-profane way to say it.”

The shimmering title track is a particular album highlight. “In the song, being cool could mean being aloof or detached or not involved,” Leadon says of his phrasing. “And I’m reflecting on that. We need to care about things. And I think we all, as we grow, need to figure out what’s important. It’s too late to be ambivalent.”

An Americana Hero

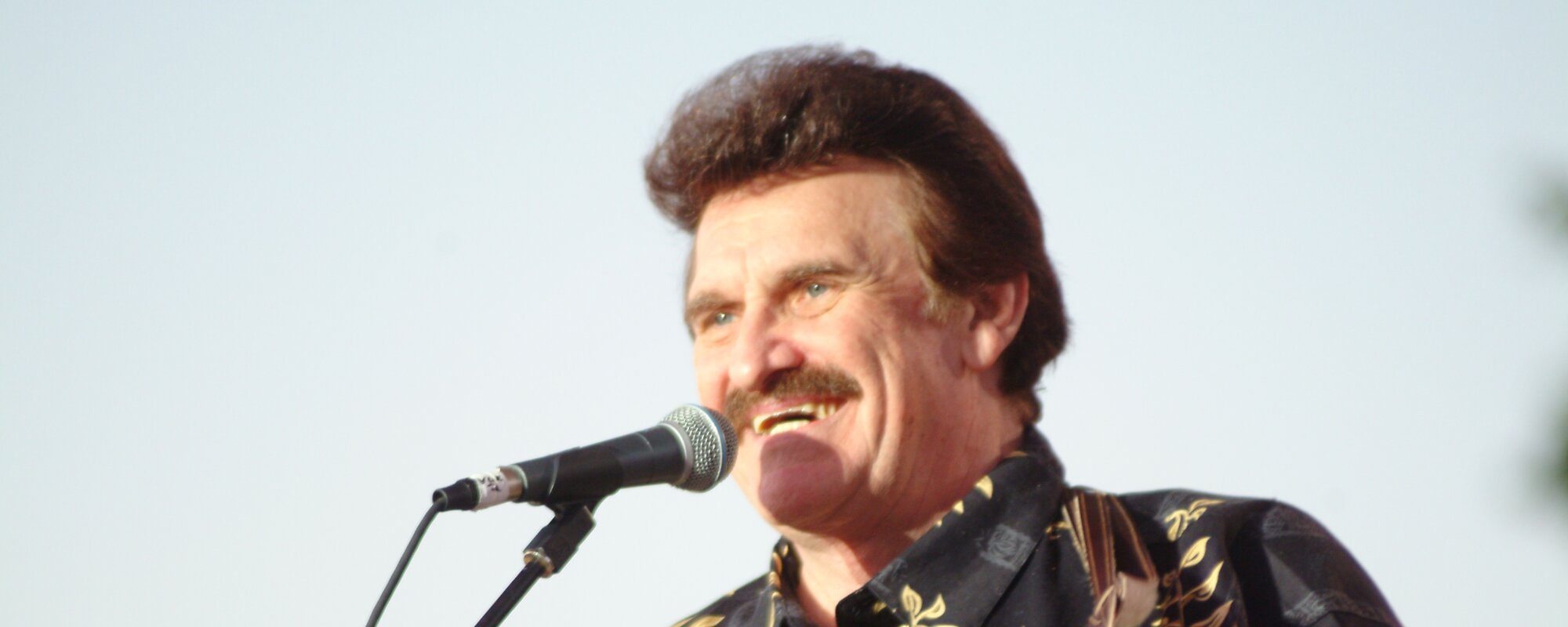

Even before the Eagles came along, Leadon was promoting the combination of country and rock with outfits like Dillard & Clark and The Flying Burrito Brothers. He crossed paths with Gram Parsons in the Burritos, which eventually inspired him to write “My Man,” a stunning album track from the Eagles’ On The Border in 1974.

“Chris (Hillman) fired Gram from the band when he didn’t show up at a rehearsal because he was out with Keith Richards and the Stones all night,” Leadon remembers. “Then Gram did a couple of solo albums, and he had me down to Capitol Records to overdub on them. A couple of days later, I flew to England to start the third Eagles album. And by the time I got to the UK, I found out that Gram had passed. While we were over there, I started working on ‘My Man’ as a cathartic thing for me.”

Despite his accomplishments and obvious impact, Leadon refuses to take too much credit for his role in initiating styles that would eventually flourish into the Americana movement as we know it today. “Dillard and Clark, The Flying Burrito Brothers, and the Eagles all had a country rock element,” he says. “But there was also The Lovin’ Spoonful in the mid-’60s. Zal Yanovsky, their guitar player, was playing country licks all over their stuff. Rick Nelson had his Stone Canyon Band. There was Poco and The Grateful Dead with Workingman’s Dead. There were a lot of groups doing something like that. I feel it was coming anyway.”

He reflects on his most famous band with a similar lack of braggadocio. “The Eagles had all the business parts together as well as the music,” he mentions. “We had outside songwriters like Jackson Browne, JD Souther, and Jack Tempchin. And we also had David Geffen for a manager, Glyn Johns for a producer. The label, Asylum, was partly owned by Atlantic Records, and it had distribution through them. We had a great booking agent. We had all the pieces you need, plus the songs, plus we could play and sing. If you have all the parts that you need, and nothing is tripping you up, then the odds are you’re going to succeed.”

Modesty aside, you can tell from listening to him that Leadon is thrilled by the experience of making Too Late to Be Cool. “These guys are great players and a lot of fun,” he asserts. “And Nashville is a wonderful place to record because everybody is so good at what they do, and they’re also nice people. We’ve all learned that you can’t show up impaired to work, so everybody showed up ready.

“We all love to eat, so I built a nice kitchen in the studio. My wife made lunch every day, and that was like lubrication for the day. The songs are relatively simple, and these guys are such great players. We captured stuff while it was still fresh.”

Leadon is preparing to tour with these musicians in the spring of 2026. When asked if he wondered, during the long interim between his releases, if his album-making days might have passed, he offered a thoughtful take not unlike those spread across this album.

“Luckily, we don’t really have to retire from doing it,” he muses. “As long as we can play and write and think and sing, there’s no reason not to if we have the means to do it. I built the means of production so I would have no excuses left.”

Maybe the album title is right, and coolness is slowly getting away from us with the passing years. But with the material contained within Too Late to Be Cool, Bernie Leadon convincingly proves there’s no expiration date on musical excellence.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.