You can generally expect Bob Dylan to zig when everyone else expects him to zag. In 1967, when the rest of the music world was awash in the trappings of psychedelia, Dylan released a series of hushed, acoustic-based songs that asked more questions than they answered.

Videos by American Songwriter

It’s an album whose most famous song received most of its notoriety because of a cover of it. The coolest thing about John Wesley Harding might be the fact that nobody has really figured it out to this day, meaning it’s always ripe for a fresh go at it.

Back from the Crash

Even in a year as dense with major musical moments as 1967, the anticipation for a new Bob Dylan record was immense. When the world last heard Dylan, he released his double-album masterpiece Blonde on Blonde. He had also completed a world tour where he seemed to antagonize as many fans as he thrilled with his electrified versions of many of his classics.

But Dylan then faded from the public eye for a while following a motorcycle accident in July 1966. To this day, the exact details of the accident are elusive. Some have speculated Dylan used it as an excuse to pump the brakes on the unsustainable pace of recording, touring, and general hard living of the previous few years.

Dylan finally returned to recording mode with a trio of sessions, produced by Bob Johnston, in late 1967. He was joined by guitarist Pete Drake, bassist Charlie McCoy, and drummer Kenny Buttrey. Bob played piano and harmonica in addition to acoustic guitar.

Long gone were the fast paces and cacophonous musical backing that distinguished so much of Dylan’s output the previous two years. This album, titled John Wesley Harding after one of its songs, featured quiet, intimate arrangements. Dylan was no longer howling his lyrics. Instead, he caressed them and spun them carefully off his tongue.

Considering this was the year of the Summer of Love and Sgt. Pepper’s, John Wesley Harding sounded as if it was being beamed in from another time. What people didn’t know is Dylan had spent much of 1967 huddled with The Band in Woodstock, New York, recording a series of weird, inscrutable demos that had a lot in common with the mysteries at the heart of this new record.

Revisiting the Music of John Wesley Harding

Clocking in at under 40 minutes for a dozen songs, John Wesley Harding seemed determined to undercut any expectations. We know it now as the record that contains “All Along the Watchtower,” but Dylan’s original version of that song is muted and noncommittal. It took Jimi Hendrix and his hallucinatory guitar to find apocalyptic portent in the incomplete tale.

At one point during the shaggy-dog allegory “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest,” a character utters the phrase, Nothing is revealed. Consider that an accurate catchphrase for the entirety of the album. Dylan wasn’t in a decisive mood, constructing lyrics that were immediately intriguing but, when taken as whole songs, doggedly impenetrable.

That’s not to say the songs on the record are somehow recessive or forgettable. By contrast, there’s beauty and tenderness to be found throughout quasi-parables such as “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” and “I Pity the Poor Immigrant.” “Drifter’s Escape” achieves a twitchy intensity, while closing track “I”ll Be Your Baby Tonight” anticipates Dylan’s move toward country and western.

John Wesley Harding confused many Dylan backers. Just when many of them had come around to the irreverence of his electric period, he largely unplugged. As everyone expected big statements, he delivered ambivalence. We may never unlock all the secrets of his album, but it remains a wonderful listen when we try.

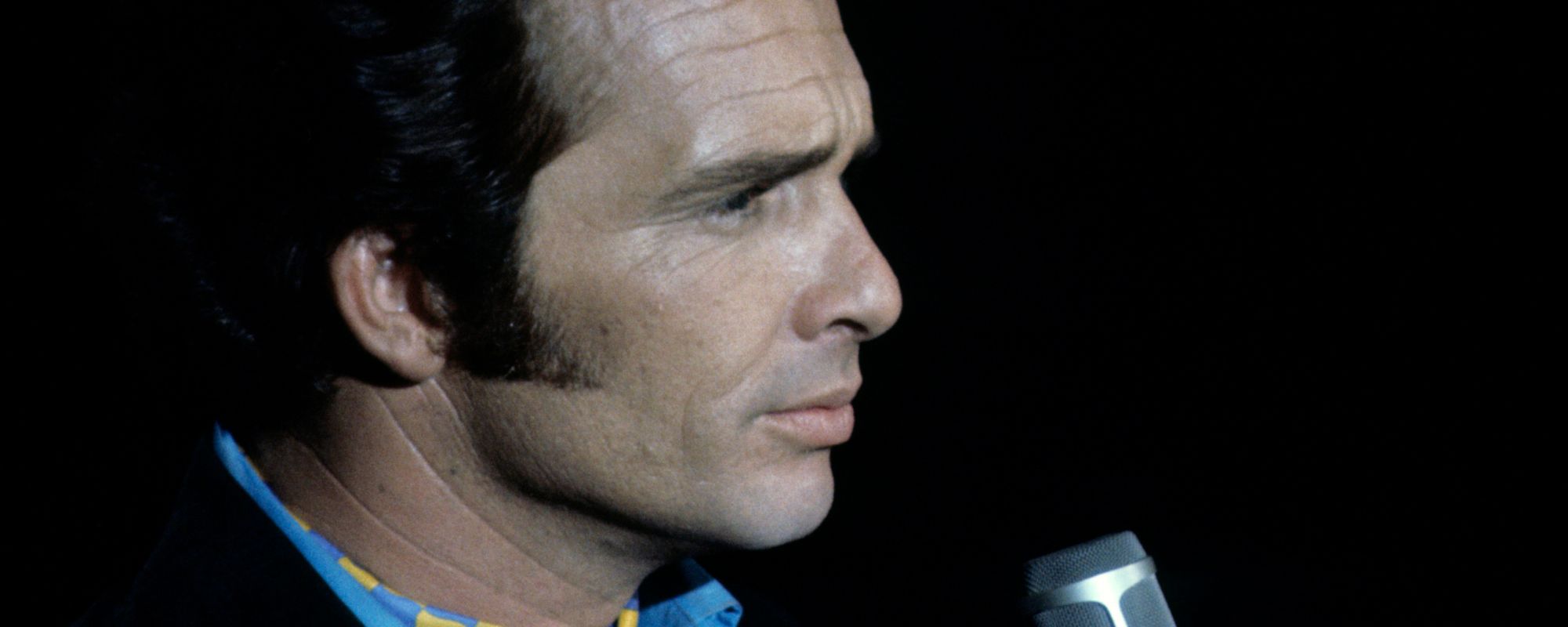

Photo by Charlie Steiner – Highway 67/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.