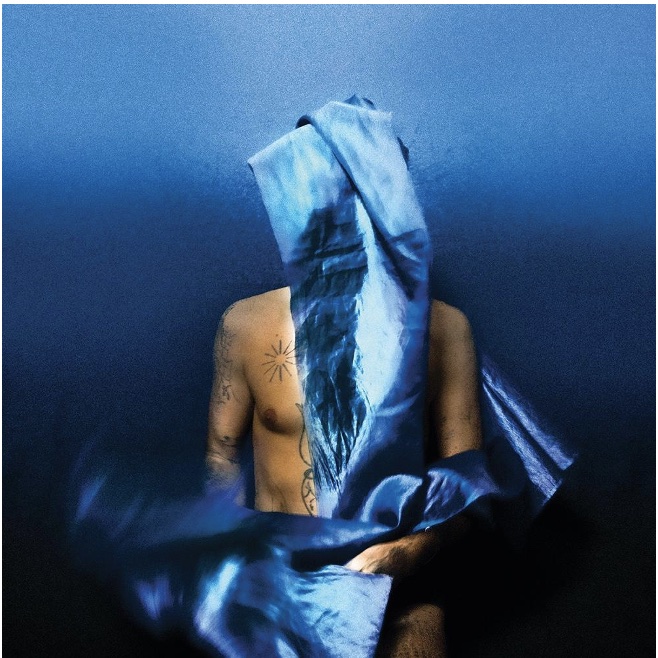

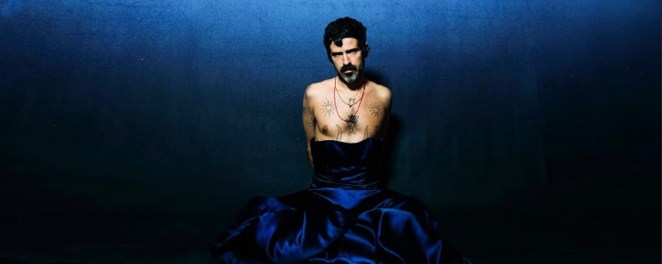

Surrounded by redwood and pine trees in a cabin studio in Topanga, California, Devendra Banhart dressed up for the occasion. Recording his 11th album, Flying Wig necessitated another persona of sorts. Dressed in a pleated, shiny electric blue Issey Miyake dress, given to him by Welsh producer and collaborator Cate Le Bon, and topped in a few wigs, Banhart succeeded in capturing some of the essence of his grandmother and a collection of songs dipped in esoteric folk, and something more narcotic, noir, and nostalgic, in nature.

Videos by American Songwriter

Gravitating within an ambient mise en scène, the narrative within Flying Wig is the American-Venezuelan singer and songwriter’s response to sadness, loss, and feeling “untethered” with each song anchored by Japanese poet and Buddhist priest Kobayashi Issa’s 1817 poem “Dewdrops”:

This dewdrop world

Is a dewdrop world

And yet

And yet

“It helped so much, and it expressed what I was feeling in so few words that it was almost like the antidote to feeling so totally untethered,” Banhart tells American Songwriter. “So it was this feeling of having something that anchors you, that can tether you to something.”

Moving through a more melancholic, meditative state, “Feeling” opens Flying Wig with its tranquil chant—I’m looking for a feeling / Hard to explain / I’m looking for a feeling / Might not come again. Each song elegantly dressed against the next, Flying Wig leaves a warm and soothing cover for the painful, distressing, and personal struggles of “Sight Seer”—I’m singing no longer for fun / But as a form of protection and its progression on “Sirens” It’s getting harder to sing / Impossible things— with both speaking to more to breaking out of more paralyzed state.

Throughout Flying Wigs, Banhart wrestles with some of the unknown but not all of it is doom and gloom, evident in “Charger.” This is his more optimistic take on facing one’s mishaps and mistakes around the metaphor of losing a phone charger—Everything’s burning down / But the grass is always green. Banhart faces fear with a more post-punk segue of “Twin” before the serenely choral close “The Party.”

Banhart spoke to American Songwriter about his mindset behind Flying Wigs, how meditation guides him, and the “paths” he often follows toward a song.

American Songwriter: You’ve mentioned “disappearing into the darkness” to write. As someone devoted to meditation, how does it play into songwriting, and did meditating help guide you at all while making Flying Wigs?

Devendra Banhart: Those seem to be all intertwined and interrelated, but totally different worlds. Meditation as a discipline is a pretty essential part of my life. It’s totally intertwined with writing songs, for sure. But neither of them guarantees some kind of inspired insight, some kind of firecracker of inspiration. So it isn’t like a song just comes out of nowhere. Of course, it does in a way, but the work that it takes for that to happen … I’ve always been so jealous of people who dreamt the song and it just came out. They witnessed something, and they felt something in them and it just poured out. That’s so magical. It’s so beautiful, but that’s never been my experience, so I’m very jealous. So even though it seemingly emerges from somewhere else, from nowhere or a mysterious place, the work it takes for that to happen never ends.

It isn’t like the flower just grew without you spending time watering it and making sure it’s in the right environment. A lot of the work is making space—inner and outer space. So we meditate to get to a space within, a space between our thoughts, one that’s a little bit more responsive, other than the reactive way that I am naturally. I meditate to be more responsive in the way I treat myself and the way I treat others, but when writing a song there are these three paths:

One is “What’s the secret? What am I keeping from myself? What’s the secret to myself? Like, what am I so embarrassed about or ashamed about or worried about? What am I pretending isn’t really there? What am I trying to keep? As a secret to myself even? So let’s go down that road. Let’s face that.

It could be something like I’m so I’m such a yogi and meditate so much. I’m above sexuality, and I know it’s bullshit. The other one is “What am I scared about? What am I really freaked out about? Maybe I’m scared of being perceived a certain way. I’m scared of saying a certain thing. I’m scared of a certain event happening.

And then the third one is: “What do I love? So it isn’t all a total bummer (laughs).

AS: Have you always been asking yourself those questions when writing, or was that something that formulated over time?

DB: How to verbalize it has been developed over time. Over time you write songs and you start to go through it and you’re wondering, “Why do you do this? What’s this thing about? How do you talk about this thing that really gets ruined once you start talking about it?” Even though I do love a concept, and I love a story. And I love a title. It can make or break that entire thing. But the story part of it is really wonderful and important. For me, at least, it’s what leads to a song, and there are these kinds of paths.

There’s a lot of self-mythologizing in the early records to where it’s here’s here all the strange symbols and codes and “these are the things that make me not like anyone else. This is what I’m about. And this is why I’m special.” But that changes that changes. That’s why I ask “What’s scary, what am I keeping from myself, or what do I really love? I asked myself those questions daily, so it’s not really something that can ever stagnate.

[RELATED: Product of Environment: Interview with Devendra Banhart (2019)]

AS: You had Cate Le Bon produce the album. How did she help these songs come together for you?

DB: There were a few moments where I would really she would just say, “Why are you crying,” and I was crying because she got it so close to what was in my head. I couldn’t believe it. I cry a lot. I cry every day, and in the most inopportune places like the post office, and the supermarket. It just happens. I was just overwhelmed with emotion because it’s so rare that it sounds just like what you’re envisioning. That was a big part of working with Cate and how close it got to what we wanted. That naturally happens when you have two people that are coming from different approaches, but really love and respect each other.

At first, I wanted to make a sunny California, jammy Grateful Dead record. Cate led us to turn it into this nighttime, dystopian, city pop, dark album, but the environment we were in was so sunny and bucolic, gentle and natural. There were hawks flying over us as we were recording little rabbits running around, and our view was a eucalyptus tree. We were recording during the day, so it was so fun for us to have this counterpoint. It was fun for us to create this dark dystopian world in such a hopeful, optimistic, and healing environment.

AS: There seems to be some struggle in songs like “Sight Seer” and “Sirens”—it’s getting harder to sing and lyrics like this. Along with the Issa poem, what kind of story were you telling with these 10 songs? What were some other things that started seeping into the songs for you?

DB: That poem was the thing to weave around. What tied all the songs together is that as hopeless as they may seem, they need to be tethered to an end yetness, which is of course, hope, this little light in the distance. So every song had to have some end yetness quality.

You’re right about the seeping in. You can’t help it. Every record, every song we write is—unless you’re writing as a character, and even then you’re taking from your own experience consciously or subconsciously—always pretty much a real portrait of where you are at that moment. It’s always fascinating when the song just came out and it’s like “What is this shit about?” Then nine months later it’s “Oh wow, that’s what it was about?” It’s some kind of neurological mercy or some psyche compassion, where your psyche is protecting you from something you can’t deal with at the moment, so it comes out in the song. It’s mysterious to you, then time goes by, and you’ve created some space between you, the event, the experience, the feeling, and the emotion, and you can deal with it. You understand what it’s about.

AS: Thinking back to The Black Babies (2003), Sight To Behold/Be Kind (2004), or older songs, some must make more sense to you now.

DB: I am referring to that stuff, for sure. I remember having that feeling on the first record going “I don’t know what this is. This seems interesting, or this seems strange or funny to me.” The shadow archetypes that reside in our subconscious are having a full-out orgiastic freakout when we’re in our early to late teens and early 20s. It’s such a transitional period. We really feel like we know everything. We consciously know that we know nothing, but we’re so convinced we know everything. It’s an incredible weirdo paradox time. Yet, you still want to write something on the cave wall. You want to be seen.

The capability of analyzing is not really developed at this time, so you do blame the world. A desire for metaphysics is pretty strong like “There’s gotta be more than this.” It takes some time to develop. All those experiences that are painful, we don’t know how to analyze, or process yet, but songwriting is a weird, intuitive way of trying to deal with that stuff. You create this whole lexicon, these words that you return to, these themes that you keep returning to and you hope that you start to realize why you were singing about these things. It’s a weird self-therapy tool in terms of the exploration of your unconsciousness.

AS: It sounds like songs still stay with you after some time.

DB: Can you think of a song that has made you cry the most?

AS: “The Ship Song” by Nick Cave. Another is Percy Sledge’s “The Dark End of the Street.”

DB: I’m crying about that [“The Dark End of the Street”] too, that the sentiment—they’re gonna find us / They’re gonna find us / You and me / At the dark end of the street. It’s so painful. It’s such a heartbreak. With Nick [Cave], I’m so with you, but for me, it’s “Magneto” and “Bright Horses. When he plays those two I go “No one look at me.” Don’t look at me. It just kills me. I love that question though, because it’s such an amazing thing that we can be so moved by. A film can destroy our world or make us want to live. A painting, if you sit with it long enough can hit you for sure, or a ballet and obviously a book. There are all these different disciplines, but a song is the shortest space where this overwhelming, heartbroken, open emotion can be created.

In the space of two or three minutes, I can just lose it and be overwhelmed by emotion, and that’s so special to me. A song is the shortest distance between us and the opening of that experience.

Photos: Dana Trippe / Courtesy of The Oriel PR