Joe Ely remembers the moment he started taking the covid-19 pandemic seriously. “When South by Southwest shut down,” he says, “that was a kick in the groin for all musicians. That’s when I realized I had to use this time, or else I was going to think myself into a hole. That’s when I started calling it the pan-damn-it.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Like everyone else in the world with a laptop and a musical instrument, Ely started streaming live performances from his home. That was fun, but like every other live stream this spring, it was more an off-handed recycling of his live show than a true creative act. And creativity is what he needed to confront this Brave New World.

“My first response to the lockdown was, ‘Wow, it’s gotten so quiet and still—the cars and people have all vanished,’” he recalls. “It went from a nice stillness to a frightening stillness—it was like the whole world had disappeared. I thought I would get a lot of writing done, but that frightening quiet didn’t go away. It took me a while before I could focus on the silence. I began looking at songs I’d started on the road; I followed them where they led, and the fear went away.”

The result was a new album of songs he completed during the “pan-damn-it.” Love in the Midst of Mayhem presents nine previously unreleased songs plus one completely rearranged Flatlanders B-side. The tunes were finished and recorded quickly because, Ely says in the press release, “I wanted these songs to be heard now rather than in six months.” He could pull off the quick turnaround because he runs his own label, Rack ‘Em Records.

This is no tossed-off, stopgap project. Love in the Midst of Mayhem deserves its place among the Texas country-rocker’s early MCA albums or his recordings as a member of the Flatlanders and Los Super Seven. Though the new disc has a couple of soft spots in the middle, there are at least three tracks destined to become highlights of his live show for years to come: “Garden of Manhattan,” “Don’t Worry About It” and especially “Cry.” And the folkish “A Man and his Dog” is one of Ely’s best story songs.

Two of the songs had their origins in the early ‘70s, while the ‘80s and ‘00s yielded one apiece. The rest are from the 2010s. They were in various stages of completion when Ely dug them out of his “boxes and boxes” of unfinished songs. Sometimes he’d find old tapes but more often all he found were sheets of paper and spiral notebooks.

“I’ve always written songs as I bump down the interstate or as I’m getting ready for the show at the hotel,” he explains. “On the bus I can play a little bit and get some work down, but it’s not till I get home that I can see what I’ve really got. Sometimes I’ll finish them, but at other times for some reason I’ll put aside a song that I was hot on the trail of. When I write the words, music comes with them, and when I pick up a lyric sheet years later, I can hear the melody I had in mind when I wrote it.”

A good song might get set aside because it doesn’t fit the theme of his next record. When he made Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, for example, he was looking for “racing-down-the-road songs,” while for Letters from Laredo, he was looking for border songs.

“This time I wanted to do love songs,” he says, “because in these pan-damn-it days, people need something to latch onto. And there’s nothing like a love song to pull you out of where you are and take you where you want to be. All that silence asked me to fill it up—and what better to fill up that emptiness than a song? Having a theme gives you a place to start and a place to end. When you’re thinking of a theme, certain songs will pop up that you never would have related to before.”

He also had another factor in mind as he narrowed down the candidates for the new album. He told himself that each melody had to be as strong as the lyrics. He had always written the lyrics first and allowed the words to suggest the tune that soon followed. For this project, however, he wanted melodies sturdy enough to work as instrumentals.

“This time the melody had to stand on its own,” he said; “it couldn’t just be a vehicle for plopping down a steaming pile of lyrics on it. It had to be the main part of the song. But I had to be careful about how I tied things together, so it all seemed like one piece.”

The oldest songs on Love in the Midst of Mayhem were begun in 1973-74, right after the Flatlanders had broken up when Plantation Records refused to release the band’s debut album, All American Music, in any format but eight-track tape. The group’s three singer-songwriters—Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock—scattered with the winds, and Ely landed in New York City.

He lived in a cold-water flat on St. Mark’s Square across from the Shakespeare Festival Theater. He’d hang out in the East Village bars with his fellow struggling musicians and come home full of song ideas. Two of them eventually became “Soon All Your Sorrows Be Gone” and “There’s Never Been” on the new album. They both combine traditional melodies and literary lyrics in spirit of the Greenwich Village folk-music scene, which was then on its last legs.

“That New York time,” he remembers, “taught me what you can do in a folk song: how to go back to where folk music began, people talking about their lives and hardships, but also how to open it up and go somewhere else. My parents and grandparents went through the Dust Bowl and they told a lot of stories about that. But it took me going to New York to really appreciate those Dust Bowl days.

“That led me to the great songwriters like Woody Guthrie and Lightnin’ Hopkins—Lightnin’ told the story from the black point of view. That led to Mississippi John Hurt and Mance Lipscomb, those folk-blues guys I really related to, because they had a fingerpicking sound and a story.”

Another huge influence was Buddy Holly. As a youngster, Ely assumed that because Holly had songs on the radio, he had to be from New York. He was astonished to learn that Holly was from Lubbock, Texas, the town Ely had moved to as a 12 year old. If a Lubbock kid like Holly could get on the radio, why not Lubbock kids like Ely and his pals Gilmore and Hancock? Their ambitions seemed more realistic than they might have if the musicians had lived in a different town.

Holly, Ely says, pioneered a rock’n’roll that boasted “gorgeous melodies with lyrics that fit into place like a jigsaw puzzle.” That approach provided a template for Ely, Gilmore and Hancock to write their own songs. Holly’s influence is all over Love in the Midst of Mayhem, no more so than on “Cry,” the new album’s highlight.

“‘Cry’ is based on a different kind of chord progression,” Ely says, “a progression that came from imagining what Buddy would have done if he were still alive. I gave Roy Orbison a copy in 1988, because I thought the song would fit him, but he died a week or two later. It has that R&B feel, that walking bass line and that high guitar walking up a half step at a time. I can’t wait to do that live. I haven’t played hardly any of this record live. It’s going to be fun.”

Because the threat of covid-19 prevented Ely from working in a professional studio or bringing a band into his home studio, the singer completed the pre-existing tracks by himself—redoing the vocals and guitar parts as necessary and filling out the sound with bass and drum machine. He made one exception: He brought in his trusted collaborator Joel Guzman to add Tex-Mex accordion and other keyboards, giving the project a distinctive borderland personality.

Though the songs don’t reference the pandemic directly, they are a response to it. In celebrating the glue of romance, the songs counteract the isolation of the lockdown. In celebrating the optimism of romance, they counteract the paranoid disinformation and demonstrations that have attacked public-health policies.

“We wanted to keep the energy up when things started turning nasty,” Ely says. “You can’t get mad at something no one had anything to do with. I wanted to smooth over the situation. It’s been a real thrill for me to do songs not for their commercial potential but just so I could see the song come to light. It used to be I had to wait years for a song to come out, but now I can put out a song while it’s still connected to the times that inspired it.”

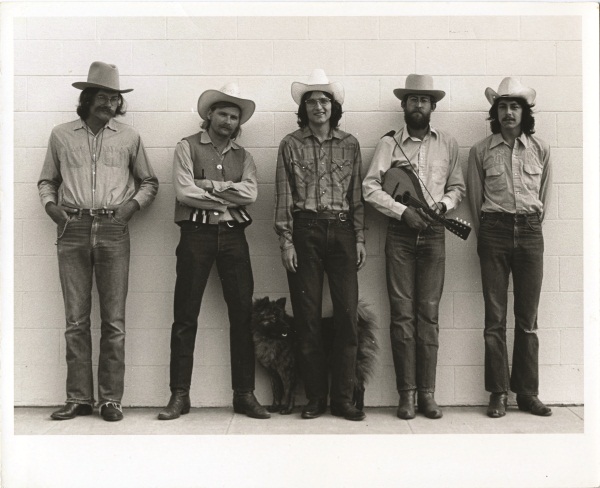

Header Photo by: Barbara FG

Cover art: Mark Seliger.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.