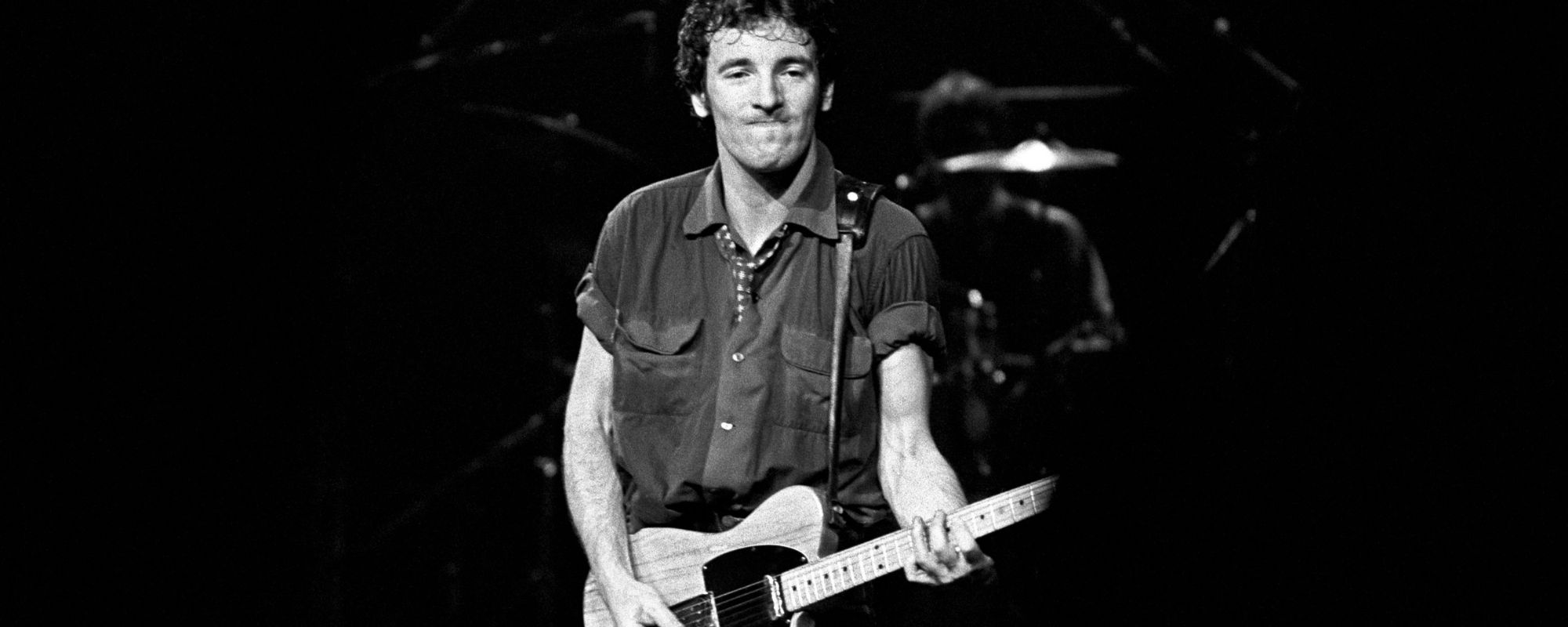

Bruce Springsteen has gained a reputation as being the ultimate perfectionist when it comes to his albums. Legends abound of unreleased, complete LPs sitting stocked away somewhere in his vaults, all because they didn’t quite fit the exact message he wanted to deliver to his audience at the time.

Videos by American Songwriter

The River, released in 1980, deviates from that formula somewhat in that Springsteen actually gave us more music than was originally intended. Here’s the story of how The Boss decided, fairly late in the album-making stage, to make it a double.

Breaking Ties

Bruce Springsteen headed into the studio in early 1979 for the making of his fifth album on an undeniable high note. The legal issues surrounding former manager Mike Appel had been settled, and his previous LP, Darkness on the Edge of Town in 1978, featured fierce performances by the E Street Band and a more adult songwriting perspective that suited his maturing audience. Not to mention Bruce was already being hailed as rock’s most invigorating live performer.

Ever the prolific songwriter, Springsteen hit the ground running with a sold base of material in those early recording sessions. A few of the songs had already been road-tested. With Steven Van Zandt added as co-producer with Jon Landau and Springsteen, a tight unit was in place to make sure things ran smooth. There was hope the new album might arrive in time for the 1979 holiday season.

Some of the material being churned out seemed lighthearted and accessible enough to court a radio audience like Springsteen had never done before. But there were still deeper songwriting moments. By late summer 1979, final preparations were being made for a 10-song album called The Ties That Bind.

River Redux

In September 1979, Springsteen and the band took a break from what they thought were the final stages of recording the album to perform at the No Nukes benefit concerts in New York City. Amidst a host of rock and roll luminaries, he and the E Street Band delivered legendary performances.

At that high point, Springsteen began to rethink what his new album should be. For one, the response from the crowd caused him to wonder if the single album was vast enough to capitalize on his momentum. In addition, he worried if he had given enough space for some of his more serious songwriting concerns, such as those expressed on the haunting track “The River,” which he had debuted live in those benefit concerts.

Springsteen began to conceptualize a record that was big enough to encompass all sides of his approach. There could be fun, loose rock songs like “You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)” and “Hungry Heart.” By why not also speak the truth about the harsher elements of life as well, such as what he had showcased throughout Darkness on the Edge of Town.

Back to the Studio

To the chagrin of his record company, as costs for the album started to skyrocket, and his band, who had to endure almost another full year of sessions, the making of the record that would come to be known as The River dragged on throughout 1980. Springsteen frantically wrote new material and the band laid it down—until a 20-song double album materialized.

The end result was far more thematically varied than anything Springsteen had ever attempted. In its way, it represented the ups and downs of existence. One minute, you could be focused on an innuendo-laced seduction a la the narrator of “Ramrod.” And the next, you can be confronting your very mortality as the protagonist on “Wreck on the Highway” is forced to do.

The River ended up solidifying Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band as rock’s most crowd-pleasing band, while also upping the ante for Springsteen as an artist. It also contained his first big pop hit in “Hungry Heart.” Little did everyone know that the lengthy process of making the record wasn’t even a drop in the bucket compared to the upcoming four-year grind heading into Springsteen’s next record with the band, Born in the U.S.A.

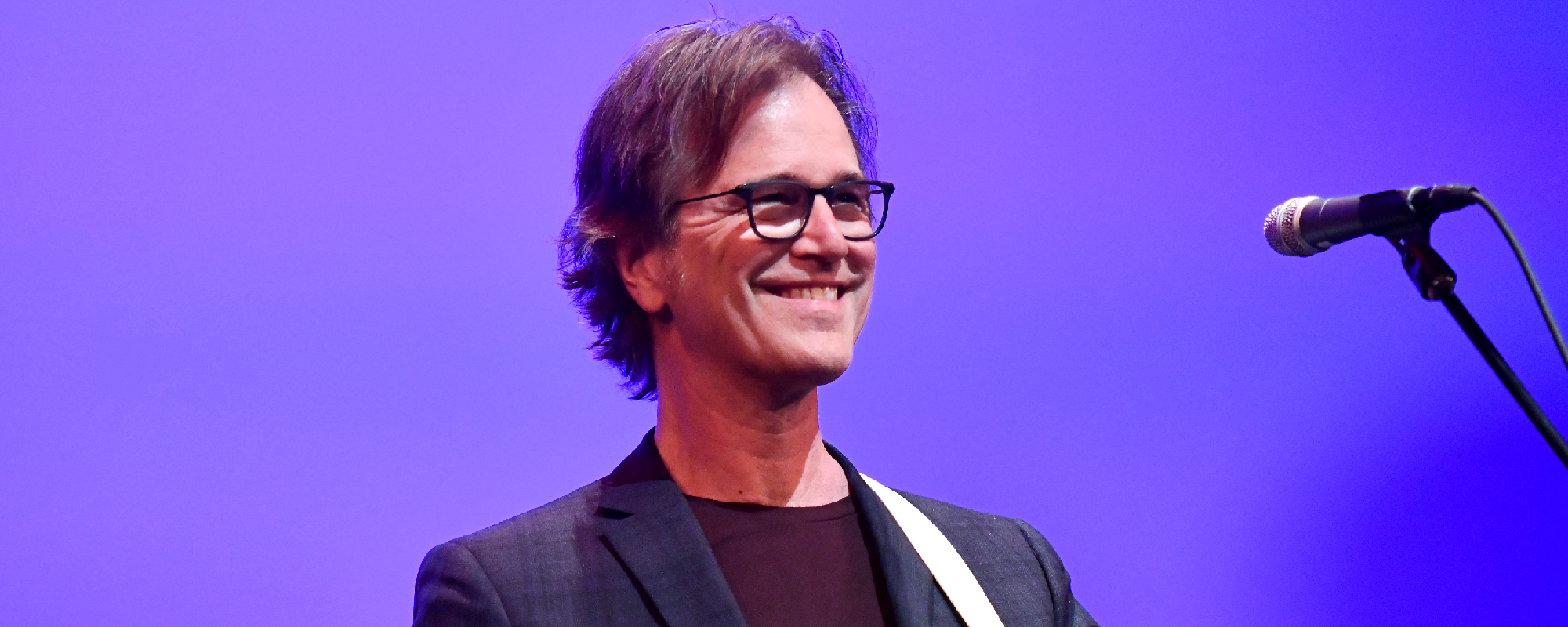

Photo by Kyle Gustafson / For The Washington Post via Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.