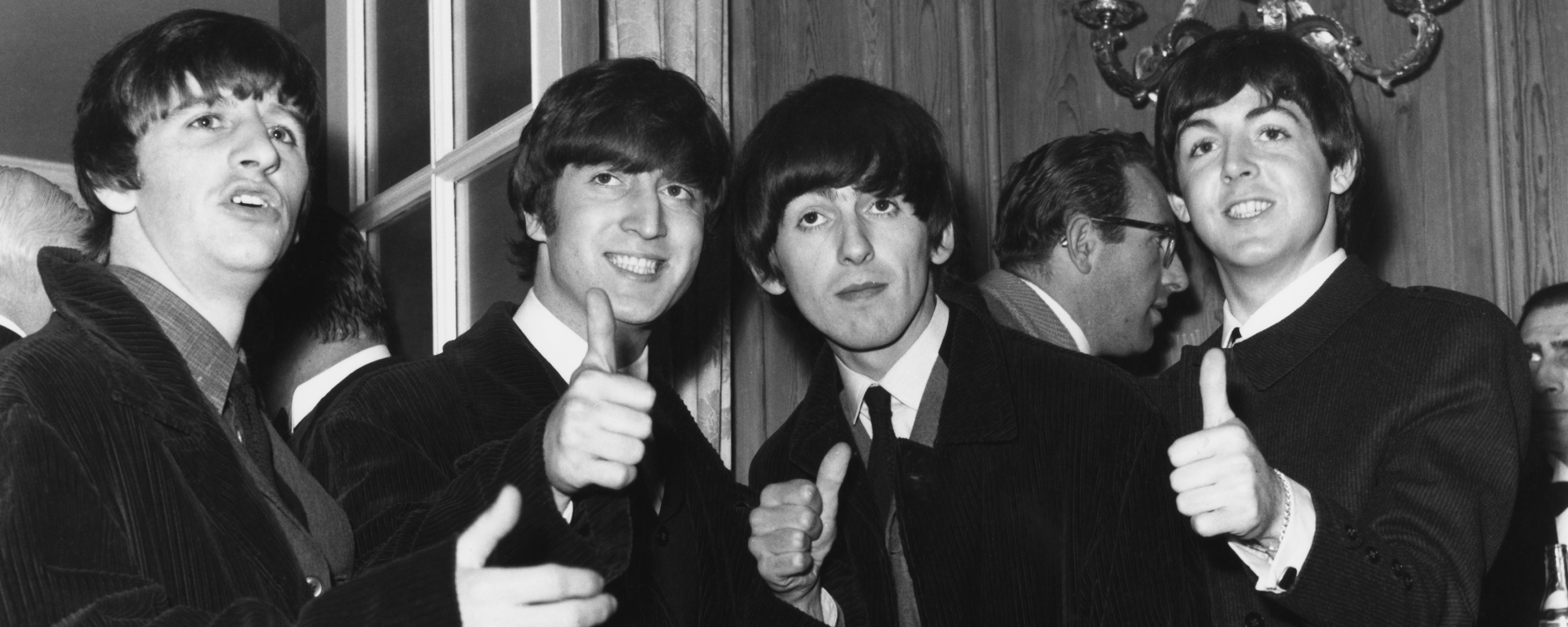

There are a many references, influences, and details that went into the interesting and often misunderstood classical piece “4’33” by John Cage. Written for any combination of instruments, it is four minutes and 33 seconds of silence, meant to capture the sound of frequencies and, when performed, the susurrations of the audience. How does someone even think of a piece like that, let alone successfully execute it? Here are just some of the intriguing details surrounding “4’33.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Composed in 1952, “4’33” is meant to capture the ambient sounds of a music hall and audience. Cage studied Zen Buddhism and chance music in the 1940s, which is music that has parts that are left up to chance or the whims of the performers. Cage had been developing an interest in silence as a way to reflect on surroundings and the psyche, and while some of his previous work incorporated silence, “4’33” is often considered a magnum opus of the concept.

When “4’33” debuted in 1952, many experts in the musical field struggled with the piece, even going so far as to try and redefine music itself. Can “4’33” even be considered music, they asked. However, this controversy was part of the concept of the entire piece. John Cage’s intention was to make the audience contemplate the established definition of music. Absolute silence does not exist; therefore, “4’33” is not truly a silent composition. But does that mean it’s music?

John Cage’s Influences for “4’33”

Cage’s Initial Idea for Silent Music

John Cage first explored the concept for silent music in 1947 while he was giving a lecture at Vassar College. He told the audience that one of his new projects was “to compose a piece of uninterrupted silence and sell it to Muzak Co. It will be three or four-and-a-half minutes long—those being the standard lengths of ‘canned’ music and its title will be Silent Prayer,” he said, according to the 1993 book The Music of John Cage. “It will open with a single idea which I will attempt to make as seductive as the color and shape and fragrance of a flower. The ending will approach imperceptibility.”

Zen Buddhism and Chance Music

Additionally, Cage’s Zen Buddhism studies contributed to the piece. In a lecture from 1951, Cage explained the concepts of “unimpededness and interpenetration,” concluding that “each and every thing in all of time and space is related to each and every other thing in all of time and space.”

Harvard University’s Anechoic Chamber

In 1951, Cage paid a visit to Harvard University’s anechoic chamber. This is a room that allegedly creates complete silence. However, when Cage visited, he reported that he heard a high frequency and a low frequency while in the room. The Harvard engineer in charge of the chamber explained that the high frequency was Cage’s nervous system, while the low frequency was his blood in circulation. This is common for those who visit the anechoic chamber; there is no such thing as absolute silence, even in a room that is supposed to be absolutely silent.

After the chamber, Cage wrote, “Until I die there will be sounds. And they will continue following my death. One need not fear about the future of music,” according to a 1961 book of lectures he published on silence.

“White Painting”

Finally, John Cage was inspired by his friend and occasional collaborator Robert Rauschenberg, who had painted a series of white paintings. These paintings seemingly looked like blank canvases, but were painted with white house paint. The shades and tones of the paint shifted depending on the type of light they were displayed in. When speaking about “4’33,” Cage stated, “Actually what pushed me into it was not guts but the example of Robert Rauschenberg. His white paintings … when I saw those, I said, ‘Oh yes, I must. Otherwise I’m lagging, otherwise music is lagging,’” according to the book Conversing with Cage, a collection of interviews published in 2003.

John Cage’s experimental nature made audiences question not only his work but the definition of music as a whole. Can silence be considered music? And what constitutes complete silence anyway? For that matter, what constitutes music? It’s a question that rattles around the psyche, and maybe silence is just what we need for some honest, deep consideration.

Featured Image by Frans Schellekens/Redferns

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.