Parker McCollum was halfway through with his new album, then he trashed it. He had recorded with producer Jon Randall, with whom he’d created multiple chart-toppers over the last few years. They had made more of the same, sure-fire country radio hits. And McCollum was bored with it. He wasn’t focused, and he knew it.

Videos by American Songwriter

“I’ve said since I was 16, ‘Songs are everything,’” he says. “You can be the best guitar player, the best singer, the best whatever, have the best management, the best label, but the songs matter more than anything else.”

He feels like he wrote and recorded “some really good songs” for his last two records, but he was so busy touring that he couldn’t dedicate himself to the album-making process. McCollum knows it’s no one’s fault but his own. Determined to do it differently for his fifth album, he took responsibility, changed things up, and started over. He enlisted veteran producer Frank Liddell to help, and then went to New York City to record for seven days.

The result is the 14-song, self-titled album, Parker McCollum, and he’s hesitant even to call it country. He’s not sure what the word even means anymore. Parker McCollum is country in the way that Guy Clark was country. It’s the kind of country more parallel to McCollum’s songwriting heroes: Hayes Carll, Rodney Crowell, and Steve Earle. And it scared him to death.

“I spent six of those days freaking out, calling Randy Rogers and calling my dad every night saying, ‘I think this is career suicide,’” McCollum says. “Then on the last day we were in the studio, I just wanted to sit and listen. They dialed everything up, and I listened to everything we had cut, top to bottom. All of those feelings went away, and I got super emotional about it.”

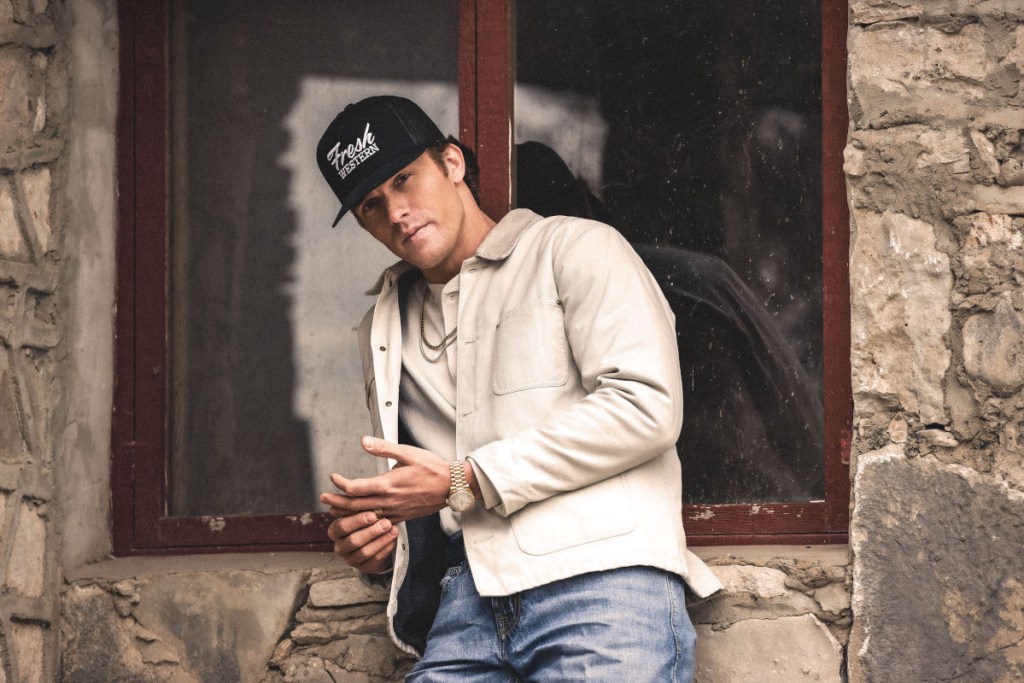

McCollum arrived at American Songwriter’s Nashville office about 30 minutes late. He climbed out of a black extended-cab Chevrolet truck wearing a starched navy button-down, coordinating flat-billed ball cap, and started apologizing as soon as he walked in the door.

“I’m never late,” he says, hugging staff members and walking toward the studio. The singer chats about his wife and son. He’d just dropped them off in Oklahoma, and his nine-month-old was spending the day at the pool. Major is crawling all over the place and trying to walk. His wife, Hallie Ray, he says, is “as good as God can make a woman.”

From listening to him talk, McCollum is obsessed with his family and happier than he’s ever been. He doesn’t always reflect those feelings in his new self-titled album.

“If you like cocaine and suicide, this record’s for you,” McCollum quips. “I was raised on very, very raw, real songwriters. My older brother was very hard on me when I was a kid about studying guys like Guy Clark, Hayes Carll, and Chris Knight. It’s a long, long list. If I ever had to show any of those guys one of my albums, this would be the album that I would want them to listen to and judge me off of.”

McCollum had met Frank Liddell once before making this album, but was deeply familiar with his work. He loved an album Liddell made for Chris Knight and intuitively knew Liddell could help him create the album he wanted to make. McCollum called him and asked. He didn’t even know if the producer, best known for producing Miranda Lambert, even knew who he was. They talked for two hours, then Liddell invited McCollum to Nashville to continue the conversation in person. The men caught up for about five minutes before heading into the studio at engineer Eric Massey’s house to record some acoustic songs. McCollum got out his guitar and started to play. They asked him to keep going, which was a different experience for the singer. Then Liddell said: “Let’s cut a record.”

“A lot of people think they want to work with me, and they really don’t,” Liddell says. “I have a different process than most. People get excited, and I know they want to work with me. Then they get into the process, and it’s not as easy. Half the time, people fail.”

McCollum didn’t fail. He was determined to maintain his focus. Liddell hired a handful of his favorite Nashville musicians, and the men traveled to New York City to track the album away from the distractions of Music City. McCollum showed up prepared and ready to work. They finished in a week.

“There’s nothing we threw at him that phased him,” Liddell says. “He played on it live, every song but two or three. He had done his homework. It was a very intense process, and I was exhausted at the end of the week, but it was also kind of easy, in a weird way.”

McCollum calls Liddell “a mad scientist genius who, I think, kind of undersells himself a little bit. He really loves records. He loves songs. And he loves a really intense emotional grind of a process in the studio. That’s how I cut my first two records when I was an independent artist.”

The singer chose to record in New York City because the town makes him feel like a rock star. The cosmopolitan energy was inconsequential, however, because they only left the studio to sleep.

And while he was prepared to record, the players weren’t. They couldn’t be. Liddell understood what McCollum wanted to accomplish with the album and chose the musicians best suited for the project. McCollum didn’t know any of them, didn’t meet them beforehand, and didn’t let them hear demos before recording. They didn’t even have charts. McCollum wanted to go in, start playing and watch the songs fall into place.

“That’s how we found our grooves,” he says. “We would just play the song for an hour, just messing around with everybody, just doing whatever they wanted to do; play what you feel and what you think sounds good.”

Before recording, they spent about an hour workshopping each song, listening to it, and charting it out. McCollum didn’t want a genre-defined agenda.

“We weren’t trying to sound like anything,” he says. “Just whatever it is that I am, that’s what this record is–really kind of unleashed. And for the first time in a long time, I just quit giving a damn about trying to be something. I was just like, ‘Whatever Parker McCollum is, that’s what I’m going to go do on this record.’”

He didn’t know what that was, or what it would sound like. The results are distinct—a sound from the unflinching storytellers he idolizes and the Texas dirt that holds his heart and roots.

“It was just such an unorthodox way of doing it compared to my last two records,” he says. “It was intense. It was emotional. It kicked my butt for about seven straight days. I ate the same meal for breakfast and lunch every morning and night in my hotel room.”

When he listens to the album now, he reminisces over how pure the week was. He doesn’t think it’s an experience he’ll be able to repeat. “It was a pretty profound, profound moment in my career,” he says.

McCollum kills two people in the album’s opening track, “My Blue.” He wrote the song about Jackie, a child born into terrible circumstances who turned to a life of crime, with Scooter Carusoe. The intro is more than 40 seconds.

“Jackie didn’t wanna run away, but he held onto his mind…was the first thing that popped out,” McCollum says of the song’s lyrics. “It fell out, and it was just, ‘Who is Jackie?’ and ‘How did it get this far?’ I figured maybe his daddy was a trucker, and his mother was a prostitute who loved Jackie, but just couldn’t take it anymore.”

McCollum wrote “My Blue” right after he signed his record deal. He loves the lyrical darkness, but knows he can’t be drawn to it in real life.

“It’s such a strange record, but I love ‘My Blue,’” Liddell says. “And I loved that song the first time I heard it.”

Liddell remembers McCollum playing it for him and Massey and declaring they were going to record it. McCollum refused, but Liddell and Massey insisted.

“We worked him over pretty hard,” Liddell says. “That was the first song we tracked in New York, and it took several hours to get.”

“McCollum co-wrote 12 of the 13 14 songs on the album, his cover(s) of Chris Knight’s “Enough Rope” and Danny O’Keefe’s “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues” featuring Cody Johnson, being the exceptions.

“Talk about daunting,” he says. “I’m not trying to be Chris Knight. But it’s Frank Liddell, who produced that album, and we were laying stuff down acoustic when we first met at Eric Massey’s studio. It was cut just to see how we worked together.”

He wrote “My Worst Enemy” with fellow Texan Wade Bowen for Koe Wetzel. McCollum sent Wetzel the self-loathing mid-tempo song, and Wetzel didn’t write back for two days. By the time Wetzel claimed it, McCollum had opted to keep it for himself.

“Koe’s one of my best friends, but if there’s one song to show the world how I feel every day of my life, this would be it,” McCollum says.

McCollum and his wife welcomed their son, Major, in August, and being a dad reframed how the singer thought about his career. He and Liddell went to New York to record when Major was two months old. McCollum kept asking himself what kind of dad he wanted Major to have. Did he want Major’s dad to be a respected badass songwriter?

The “Burn It Down” singer has charted four No. 1 songs on country radio to date, and he’s proud of the albums he made with Randall. But it was time for him to know if he was good enough to write and record the album he had always wanted to make, even if it meant risking everything he’s built.

“It takes a lot of guts to do what we’ve been doing the last few years, including the number ones, the hits, and the sold-out shows, and hang it all out there on the limb,” he says. “This record could absolutely flop.”

He’s done everything he wanted to do in country music–besides write the album of his dreams, the kind he knows will make his son proud. With Parker McCollum, he’s done that.

“I wanted Major to grow up and know that his dad did things his way,” McCollum says. “It’s really hard to go against the grain, and this industry can kind of eat you alive sometimes. There’s a lot of temptation to follow trends. I’ve never done that. This is the kind of dad I would want him to have.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.