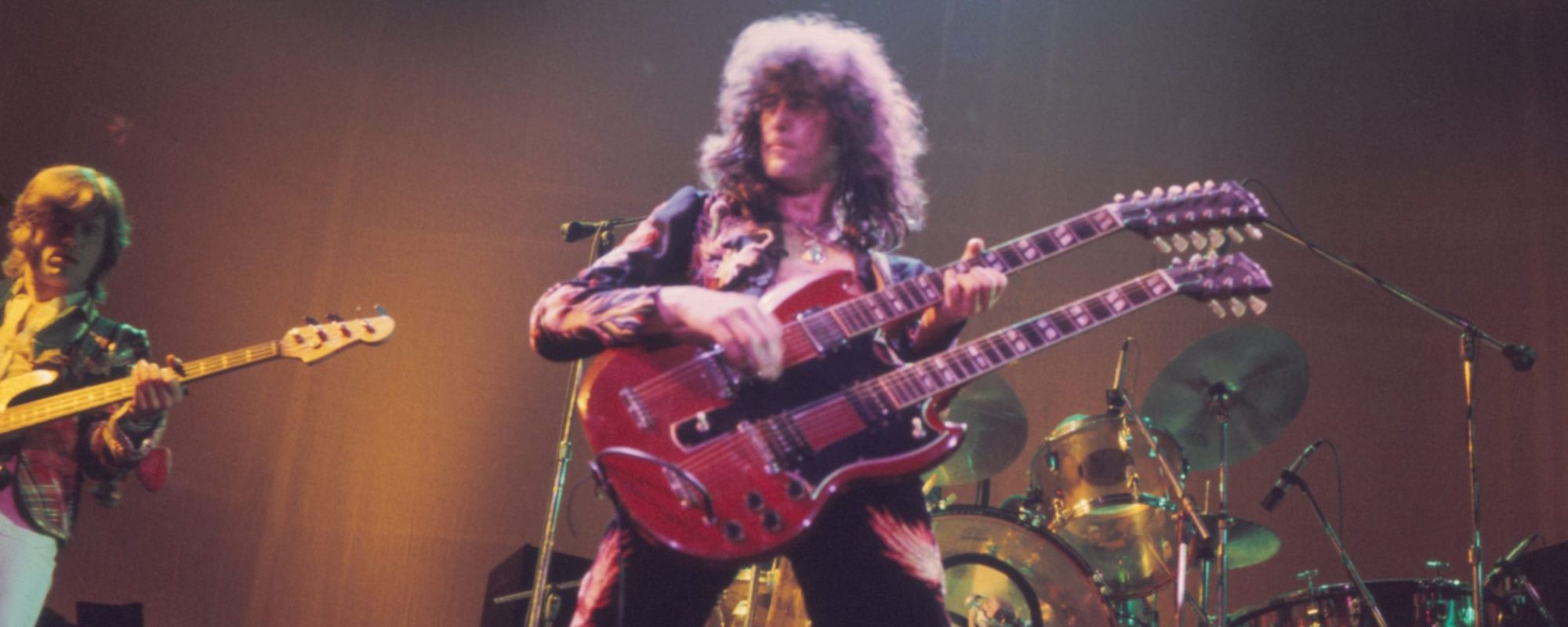

Even with Jimmy Page’s searing guitar solos, Robert Plant’s wailing vocals, and John Bonham and John Paul Jones’ driving rhythm section, one could reasonably argue that without the honorary fifth member of Led Zeppelin, Peter Grant, there would have been no Led Zeppelin. In fact, there’s a good chance that the band that would become Led Zeppelin would still be touring (and likely disbanding) as The New Yardbirds. Grant changed it all.

Videos by American Songwriter

This towering, impressive figure of a man went from working in a sheet metal factory to dipping his toes in the entertainment industry with small film roles as guards, commandos, and other castings that called for a man of Grant’s size and stature.

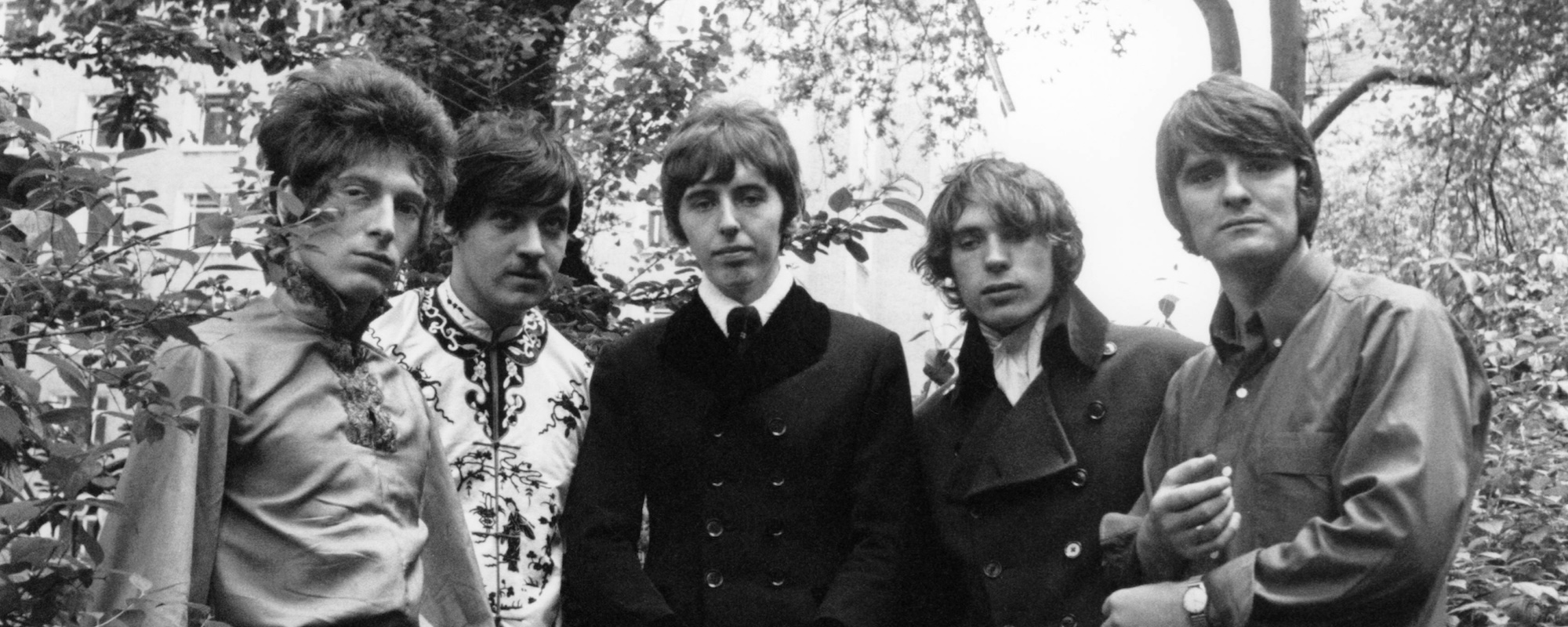

By the early 1960s, Grant was managing acts like The Everly Brothers, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry. In 1966, he turned his focus toward The Yardbirds. After the band split three years later, he followed former Yardbirds member Jimmy Page into his new project, The New Yardbirds, which later became Led Zeppelin.

Aside from the music itself, Grant was largely responsible for Led Zeppelin’s financial and cultural success. Interestingly, though, most of his business practices would falter today, despite being revolutionary at the time.

Peter Grant Was a True Musician’s Manager

Musicians have notoriously gotten the fuzzy end of the lollipop when it comes to business dealings, and that was certainly true in the late 1960s when Led Zeppelin (and the rest of Peter Grant’s clients) were cutting their teeth. Led Zeppelin’s manager renegotiated contracts with venues so that the band got paid better for live performances.

At the same time, he prioritized those live performances over television appearances so that if people wanted to hear Led Zeppelin, they had to buy a ticket. Grant also opted not to release Led Zeppelin’s hits as singles to encourage the consumption of entire albums. It was good business for the band and Grant alike, who all split the profits from these dealings evenly five ways.

Bassist John Paul Jones later said Grant “trusted us to get the music together, and then just kept everybody else away, making sure we had the space to do whatever we wanted without interference from anybody—press, record company, promoters. He only had us [as clients] and reckoned that if we were going to do good, then he would do good. He always believed that we would be hugely successful, and people became afraid not to go along with his terms in case they missed out.” Jones added, “But all that stuff about renegotiating contracts through intimidation is rubbish. He wasn’t hanging people out of windows and all that crap.”

His Business Practices Would Look Much Different Today

Peter Grant might not have been hanging people out of windows, technically, but he was still a force to be reckoned with, and industry vets knew that. Sure, he was physically intimidating from his height and weight alone. (He used to be a bouncer before his tenure as a band manager, and it’s easy to see why.) But Grant wasn’t afraid to get physical when he needed to, either. He would famously shake down record shop owners selling bootlegs and destroy what he believed to be recording equipment at shows to protect the band’s music from leaking without their consent or adequate compensation—even when that recording equipment was actually a noise pollution detector.

As Grant himself said, “I don’t believe in pussyfooting around. That’s what [Led Zeppelin] hired me for. But as a supposed archetypal ‘heavy,’ most of these incidents have been on-the-spot situations, not the result of me sitting in an office and hiring a crew of heavies to go round. Let me put it this way. I would step on anyone who f***ed around with my band personally. I would never send in a heavy; I’d deal with it myself. Just as I would go to any lengths to get the band the money they were due.”

In today’s world of brevity and online availability, it’s hard to imagine Grant’s business practices would be as successful. His ethos of putting bands in front of audiences, paying them fairly, and getting consumers to buy into entire concept albums came at just the right time in rock ‘n’ roll history. Any sooner or later, and it might not have worked.

Grant died after suffering a heart attack while driving on November 21, 1995. He was only 60 years old.

Photo by Eric Harlow/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.