Videos by American Songwriter

Bruce Springsteen

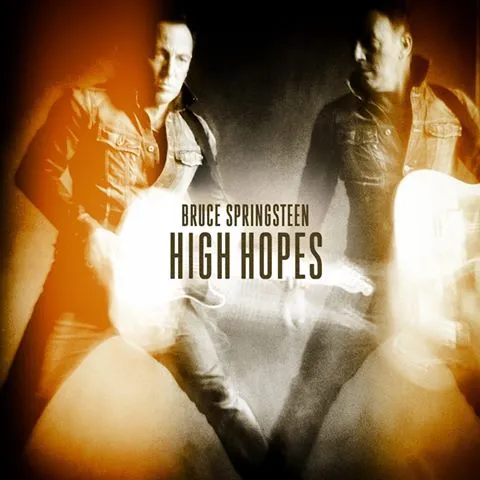

High Hopes

(Columbia)

Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars

When deciding on material for 2006’s We Shall Overcome, a collection of songs popularized by Pete Seeger, Bruce Springsteen said he picked the ones he “heard [his] own voice in.” For his new album, High Hopes, Bruce has once again turned to old songs for inspiration, but the 64 year-old singer utilizes a very different body of source material for his follow-up to 2012’s Wrecking Ball. Once endlessly selective with his own recordings, Springsteen has loosened his grip and become his own folk archivist on High Hopes, mining outtakes, cover songs, and fresh recordings of previously released material to help tell his latest story.

One of the album’s peculiar joys is that the New Jersey rocker sounds most like himself when he surrenders songwriting duties, whether on the bleak, defiant third verse of the Tim Scott McConnell-penned title track, or with the glimmering E Street soul-pop on the Saints’ “Just Like Fire Would.” Producer Ron Aniello has a knack for repurposing Bruce’s older material, and “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” now laced with feedback and a guest verse from Tom Morello, feels newly vibrant. For a record with such disjointed origins, Springsteen’s 18th studio album is a compelling, unified statement: part grief and grievance, part love and transcendence.

In the 21st century, the Boss has generally played the role of revivalist preacher, celebrating faith and hope through his records and his sermonizing on stage. At their worst, the songs on High Hopes retread the enlightened spiritualism that Springsteen has been delivering since The Rising without complicating any of its well-worn tenets. The Bar-Mitzvah gospel of “Heaven’s Wall” feels like a forced grab at biblical uplift, while the Celtic-tinged “This Is Your Sword” is a self-serious lesson in strength and courage that overworks its metaphor.

But any doubts about the continuing need for Springsteen’s modern day communal healing fade early, when the sinister groove that runs through the shady underworld of “Harry’s Place” fades, hauntingly, into the murky waters of feedback and echo that introduce “American Skin (41 Shots).” Both songs rely on the same type of sharp specifics that gave life to Springsteen’s earliest records, but now Wild Billy and the Magic Rat have turned into Chief Horton and Seesaw Bobby – violent, bitter men who whisper “we do what we must do” to anyone willing to listen. All grown up, their intentions have gone sour with age and power. It is in this dark underworld, one that allows for Amadou Diallo and Trayvon Martin to be killed without consequence in the back-alleys behind “Harry’s Place,” that there is such dire need for the cries of help, peace, and communion in “American Skin.”

On Wrecking Ball, it was easy to pass over the understated love songs “This Depression” and “You’ve Got It” in favor of the big-mouthed, full-band rave-ups that defined most of the record. They’re much harder to ignore on High Hopes, which finds Springsteen at his best when playing the role of unabashed romantic. “I feel you breathing, the rest is confusion,” he sings on the clear standout “Hunter of Invisible Game,” trying to hold on to what little he has left in a post-apocalyptic dystopia. The loose, bar-band romp “Frankie Fell In Love” finds Shakespeare giving some advice to his buddy Einstein, who is struggling to scribble down love’s equation. “Man, it’s just one and one makes three,” Shakespeare answers with a smirk, “that’s why it’s poetry.”

High Hopes plays very much like a sequel to Wrecking Ball, but Springsteen is less angry and blaming, more cheerfully weary this time around. “These days I spend my time skipping through the dark,” he sings halfway through the record, in a line that sums up his meager high hopes better than any. Thirty years later, the dancing has mellowed to a skip. He’s put his finger down, no longer blaming robber barons and greedy thieves for the desolation all around him. Instead, he’s heartbroken, wistful, and resigned, and his preferred tonic, as always, is human connection. “Come on and open up your heart,” Bruce sings on Suicide’s “Dream Baby Dream.” That prayer of love, which closes the album, is a well-aged, comfortable notion from Springsteen, and right now that’s how he prefers them.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply