Dave Stewart apologizes for the short-circuit connection at sea. Aboard the QE2 (Queen Elizabeth II), Stewart, tired of jet-lag-induced transatlantic flights, opted for an alternate route, setting sail for a six-day voyage crossing the Atlantic to England.

Videos by American Songwriter

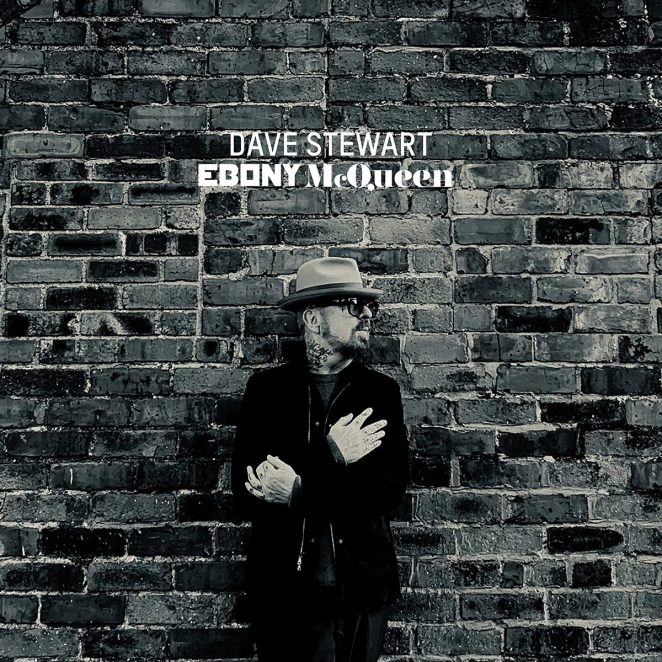

Arriving in his home country by ship also fits the grandiose nature around the release of Stewart’s new album, a collection of 26 songs sketched around his teenage coming of age years in the northern England city Sunderland, all set around an alternate reality of a voodoo blues queen visitation that sets in motion the rest of his life—the music, the knowledge, the love—on Ebony McQueen.

Written and produced by Stewart, Ebony McQueen—available as a deluxe multi-format box set with three vinyl records, two vinyl EPs, two cassettes, and a photo book with typed lyrics and an original film “scriptment”—was partially recorded at John and Martina McBride’s Blackbird Studio in Nashville as well as his own Bay Street Recording Studio in the Bahamas, with the addition of the 60-piece Budapest Scoring Orchestra, a centerpiece that made the music flow like a working score, something Stewart would later utilize to expand the Ebony McQueen album into a musical film.

Ebony McQueen is Stewart’s musical memoir, a slice of his teenage life, between 1966 to 1968, from the ages of 14 to 16, moving through familial turbulence and the personal letdown of leaving his soccer dreams behind to enlightenment: the discovery of music via Delta blues and turning on the radio to a world of The Beatles, The Kinks, Small Faces, and The Who.

“From that moment, it blew my mind,” says Stewart of his earlier musical discoveries, from playing the Robert Johnson compilation King of the Delta Blues, an album his cousin had sent from Memphis to becoming glued to the radio. “It was an avalanche of great songs, and great acts, great bands, all the way through to ’71 and later with David Bowie and Neil Young’s ‘Harvest Moon.’ There was just so much music that was so brilliant, that if you were learning how to play the guitar, like I was from 14 years old, it was very inspiring because all of these songwriters and musicians, from [Pink] Floyd] and everybody, they were making very experimental music.”

Stewart added, “They weren’t trying to follow any adult contemporary or other charts. It was just all coming out of BBC Radio One. Every song that came on, you were like ‘wow.’”

“Quaaludes Prelude” intros the hallucinatory whirl of everything ahead, referencing the first time Stewart took drugs and his first concert that never happened. “We were going to see a band for the first time at the church hall—we were excited and about 14,” remembers Stewart, who took quaaludes (then called mandies), with a friend whose mother was a doctor. “He said, ‘Hey, take one of these, and we’ll drink this cider,’ so I took one and we jumped around, which made no sense with cider, and then I don’t remember much after that. It [the show] never happened. God knows what else happened. We came around about three or four hours later lying outside the church hall.”

Upon first acquaintance, “Ebony McQueen” still reflects Stewart’s hazier beginnings around music, met somewhere between the awake- and dream-state—I think I met her once inside a time machine / She was working on an island made of green / And she already knew everything about my story … She speaks my language fills the spaces in between / So I don’t need to talk and all I do is dream.

Throughout the more than two dozen tracks, Stewart time travels from his earliest references to music and love, from the psychedelic-pop of “When You’re Feeling Down” and “She Knows Me Well” to the whirling sense of place and transition on hypnotic tremolo-d vocals of “Walking on Blue.” The tender acoustics of “People Change” and “Unhappy Town,” move through the jam out of “Things Will Never Be the Same (Without You),” while life transformations keep pulsating around the tripp-y “There’s Got to Be. Devil.”

Mid-way in, the bluesy queen returns on “Ebony Says,” urging him to keep going forward—Ebony says / You’ve just got to go through it / Ebony says / Everybody does / Ebony says / You just got to live through it / Cos there’s no way out / And there’s nowhere you can hide—and returns again for a short while on a dreamier “Ebony Dream,” a precursor to the closing tangle of words and sounds on “Loada Coda.”

Expanding on the saga of the album, Stewart has already written the second draft of the Ebony McQueen movie, mirroring the storyline of the songs, with a stage musical on the way.

“It’s a story of my slice of my teenage life when all I wanted to do is play soccer, but my knee was broken into several parts, and my mom had left my dad, and my dad was depressed,” shares Stewart of the correlation between the film and the album. “My brother had gone to college, so there was an empty house.”

Having never played a vinyl record before, the blues was his gateway. “I put it on, and I went into kind of a trans,” shares Stewart of first haring Robert Johnson. “I’d never heard anything like it. It sounded like something came on earth. I was in shock.”

In the film, the kid playing Stewart hides the blue record under his bed, and when he returns to his bedroom, the voodoo queen, Ebony McQueen, is waiting for him, in the flesh. “She becomes his guide through his teenage trauma, through his anxieties in life, and helps him cope with everything,” shares Stewart. “She remains throughout the movie, while he discovers music and discovers the girl next door, and as he discovers the possibility that there’s another life that can happen outside of a very depressed town at the time.”

He adds, “He saw no future there, like the Sex Pistols song.”

Stretching from music to love, Ebony McQueen tells the story of the Indian girl next door. “She’s playing cassettes in her backyard, and you recognize a kind of blues feeling,” says Stewart of his first love. “He falls in love with her, and she falls in love with him, so it turns into that first love coming of age movie. They start making music together, and then something very dramatic happened that could ruin everything. The whole thing is based on my teenage life.”

As for the film score, and the inclusion of the Budapest orchestra, much of the musical elements were also derived from Stewart’s younger years, listening to his father play Rodgers and Hammerstein and singing along to the theater duo’s hits Oklahoma, The South Pacific, and The King and I every day at 5 in the morning.

“This was drummed into me between the age of 5 and 10,” shares Stewart. “When I was about 6, my neighbor reminded me that I would march up the streets singing ‘I Enjoy Being a Girl’ [from ‘Flower Drum Song’]. The orchestrations and the arrangements by Rodgers and Hammerstein in those musicals were brilliant, so I tried that with the song ‘Ebony McQueen.” It’s like this big orchestral arrangement number, and all of that comes from my dad.”

Bouncing between his smaller studio in Nashville and a large one in the Caribbean, Stewart, who was recently inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (with Eurythmics) and the Songwriters Hall of Fame, is in between working with Joss Stone and the musical The Time Traveller’s Wife, due to premiere later this year.

“I can go between the two without altering much,” says Stewart of his studio shuttling from Nashville to the Bahamas and only enduring the one-hour time difference. “I was getting so fed up both flying all the way to England from Los Angeles,” says Stewart. “I hate jet lag.” He laughs, “That’s why I’m on this ship.”

For now, there’s no rush. His nearly week-long journey at sea is serving as the perfect writer’s retreat. “It’s a slow crossing, but it’s brilliant for writing,” says Stewart. “You can just sit outside on the deck if it’s not raining. Impermanence is a very important thing for a writer because it allows you to not be connected to any particular thing. You’re moving. That’s why floating at the sea is calming, because it’s constantly changing, and I find that is a great thing for writing.”

Stewart adds, “That’s why I built the studio on the island. You can spend half an hour just with a journal or a notebook. It just has this free-flowing effect, like the sea itself.”

Photos: Courtesy of Milestone Publicity