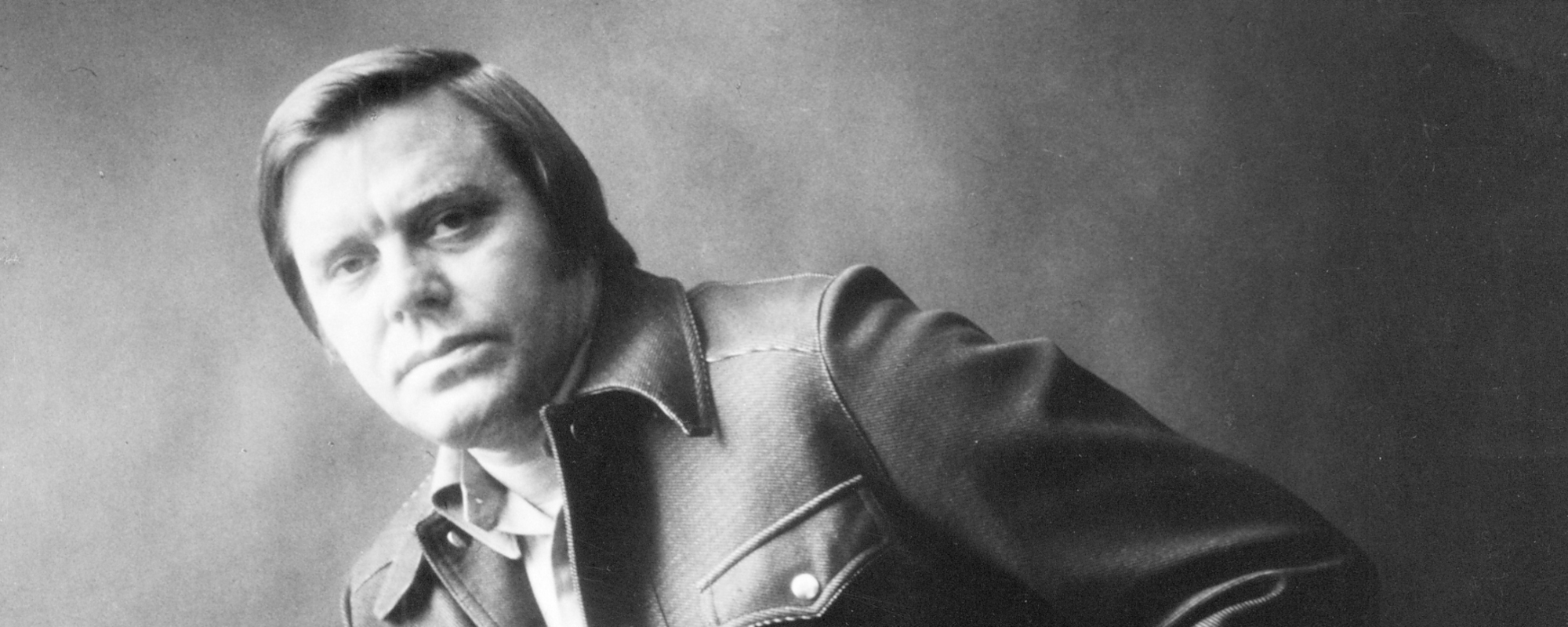

Though it took him awhile to become a household name in Americana circles, throughout his career, Del McCoury has demonstrated time and again he has impeccable timing. Whether meeting Bill Monroe at the precise moment the Father of Bluegrass needed a new lead vocalist in 1963 or greatly expanding his following by taking a shrewd turn as Steve Earle’s backing band in 1999, he has proven his timing is perfect both when charting his course as an artist and when he is making a G-run on an acoustic guitar. Though it took him awhile to become a household name in Americana circles, throughout his career, Del McCoury has demonstrated time and again he has impeccable timing. Whether meeting Bill Monroe at the precise moment the Father of Bluegrass needed a new lead vocalist in 1963 or greatly expanding his following by taking a shrewd turn as Steve Earle’s backing band in 1999, he has proven his timing is perfect both when charting his course as an artist and when he is making a G-run on an acoustic guitar. With the current financial crisis ravaging America’s financial institutions, McCoury again proves his foresight with Moneyland, a collection of songs by artists ranging from Merle Haggard to Bruce Hornsby that express the deeply felt concerns of people struggling to make ends meet. In the process, he has made an album both remarkably timeless and unfortunately timely, a stirring testament to our ability to persist through hardship and an elegy to a lost way of life.

Though it took him awhile to become a household name in Americana circles, throughout his career, Del McCoury has demonstrated time and again he has impeccable timing. Whether meeting Bill Monroe at the precise moment the Father of Bluegrass needed a new lead vocalist in 1963 or greatly expanding his following by taking a shrewd turn as Steve Earle’s backing band in 1999, he has proven his timing is perfect both when charting his course as an artist and when he is making a G-run on an acoustic guitar. With the current financial crisis ravaging America’s financial institutions, McCoury again proves his foresight with Moneyland, a collection of songs by artists ranging from Merle Haggard to Bruce Hornsby that express the deeply felt concerns of people struggling to make ends meet. In the process, he has made an album both remarkably timeless and unfortunately timely, a stirring testament to our ability to persist through hardship and an elegy to a lost way of life.

Videos by American Songwriter

So how’d you go about picking the songs for this record?

Well, I had a lot of help in that. My manager, Stan [Strickland], it was kind of his idea to do this. I came up with that song, “Moneyland.” I said, “This is a great song, and I’d like to record it.” And he got to thinking, and I did, too, that we ought to do an album to call attention to the way things are right now. That’s the way the album came about, and we started to talking to other people about it, and they wanted to submit songs. Most of them are friends of mine. So we approached them about using a song that suited the album, and we got permission from them all to do that, and it worked out good.

Was there anything in your community that inspired you to make an album like this?

Well, yeah, just the way things are. It’s like Bruce Hornsby said in his song, “That’s just the way it is.” It’s a shame. You see, my dad was too old to go in the Second World War, but he worked in a defense plant. And when the war was over, he bought a farm, and he told my mom, “We better buy a farm, because we might starve to death.” Things might get bad. The war made prosperity. Everyone had a job and could work. We figured that after the war, all these jobs were going to go and that he better buy a farm so that we could have a cow and chicken and not starve to death. But when the war was over, prosperity was just starting in the ‘50s. We really wouldn’t have anything to worry about. And that lasted until lately when we started losing our jobs to other countries and the corporate farmers came, and they’re doing well, but the family farmer-it’s really rough on them. And these oil guys charging us so much money that people can’t even afford to drive to work. It’s a shame. We’re just hoping that something will come of it.

Do you see a lot of practical solutions for these problems?

No, I don’t. I’m really ignorant as to how to fix any of this. But I can sing about it! I’m sure that up there in Washington, D.C., those guys could fix it if they would. This friend of mine, he’s a member of the Opry down here, Trace Adkins. He has a daughter who is really allergic to certain foods, and he said he’d go up to Washington to sit down and talk to certain Senators. And they listened as intently as they could, but at the end they said, “Man, we’d really like to help you if we could.” He said, “I was really just wasting my breath up there! They’re not going to do anything about that.” But I’m sure they’ll do something up there in Washington because there are too many people hurting today.

Do you think music has the power to change people’s minds?

I think it really helps to get people’s attention and to get people organized and into lobbying these things. I think it does that. We did the album, and it’s pretty serious all the way through. This friend of mine wrote this song “Forty Acres and a Fool,” and it fits this album, but it has a little comedy in it, and it breaks up all this seriousness.

So what inspired you to perform The Beatles’ “When I’m 64” for this record?

Well, he’s talking about retirement. I’ve got a house up in York, Pennsylvania, and the porch needs fixing up there, and I called this guy who came out and gave us a bid to fix this porch. And he says, “Now, I won’t do this work. My sons will come out to do this work.” And my wife says, “Well, what will you do?” And he says, “I’m an engineer, but my job went to China, so I’m working for my sons now.” That’s hard to believe, because the guy has a great education and is an engineer, but he can’t retire from that company where he started. Companies used to keep people until retirement time. Nowadays, if a young guy gets a job, he has no guarantee that he’s going to be able retire there. That’s the reason we recorded that song. But I’m way passed that age.

Is there any retirement plan for bluegrass musicians?

Well, really, there isn’t. You just have to watch your money. I know some guys that are millionaires from playing bluegrass music. One of them is Ralph Stanley and another was Jimmy Martin. Bill Monroe made three fortunes, but I don’t think he saved any of it. Earl Scruggs is one of the richest men in Tennessee. He and Eddy Arnold. They bought land. That was their retirement. I guess if a person is smart, he can do that. Those guys were.

I should have heard “When I’m 64,” but when that song came out, I was working the road with Bill Monroe. He was a member of the Opry. He joined in 1939, and we were doing the Opry and running the roads all the time. There was TV back then, but we didn’t really see that much of it, being on the road all the time. I didn’t really know who The Beatles were. I’d just heard the name. I’d never heard this “When I’m 64” until not long before I recorded it. But what a great song. When I listened to music, I’d always listen to bluegrass. I missed a lot of the rock and roll.

So have you gone back and listened to those Beatles’ albums?

No, I haven’t done that, but I’m kind of busy. Sometimes my sons will know about a song that they think I might be interested in recording, and that’s the way I get to hear things.

Do you remember the first time you heard bluegrass music?

Well, when I was growing up, my father and my oldest brother-he’s nine years older than me, my oldest brother-they would listen to the Grand Ole Opry. This was pre-television days, in the ‘40s. There weren’t that many people that had television until the late ‘40s, so they’d listen to the Grand Ole Opry every Saturday night, and that was entertainment. It was 50,000 watts clear channel, WSM was then, so at night it would just go forever. So that was the first time I heard bluegrass, hearing Bill Monroe on there and not realizing that the guy that invented it I was listening to right then. Of course, from that all these other bands came. Flatt & Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, the Osborne Brothers, the Stanley Brothers-they all came from there. I was second generation of bluegrass, although I did work for Bill Monroe in 1963. Then in 1965, we had the first bluegrass festival, and from that everything grew. People started coming to those festivals from Japan and Europe, and the music just started spreading. It became internationally known from that. Then 20 years after that, we organized the International Bluegrass Music Association, and we’ve had an awards show ever since. I’ve seen it grow a lot since then. The music is really popular now. I’ve heard some people say, “We don’t want it to get too popular.” Well, I say, “It needs to get popular because it’s good music.” It’s like how sometimes you’ll hear a bluegrass musician in a commercial or a movie, but you never really hear a good hardcore bluegrass band. Like that Deliverance. They had a guitar and banjo in there, and Don Reno-he was an ex-Bluegrass Boy-and he teamed with Red Smiley. But that was a watered down version. It’s getting better today. It’s getting to be that they are using some really good musicians now.

Do you remember the first time you met Bill Monroe?

Yeah. I saw him in 1950. They used to play these drive-in theaters that had these movies. That’s when all these drive-in theaters came in, after the second war. These bands would go and play between the movies. They’d stand up on the roof of the refreshment stand. They’d have a microphone, and their music would go out in the speakers in the cars that they’d hang on the windows. After the song, instead of applauding, they’d all blow their horns. So that’s where I saw Bill Monroe first, and it was really exciting. They were all dressed up. They wore Stetsons back then and riding boots and pants. He was a great foxhunter. He had horses and rode horses, so that’s how he dressed, back before I went with him. By the time I joined him, he wasn’t wearing riding britches anymore. Before that, that’s how him and his band dressed-these big, tall black boots, and those riding pants and hats. Oh, they looked sharp.

Were you nervous the first time you met him?

Oh yeah. I really was. That was the first time I saw him, and I would have been 11. But the first time I met him, I played with him. I was really fortunate. I was playing in Baltimore in a club for a guy named Jack Cook, and he had been with Bill Monroe for about three years, as his lead singer and guitar player. At this time, I was a banjo player, and I was working for Jack. And Bill came to Baltimore, and he needed Jack to go with him to play Town Hall in New York City, and he didn’t have a banjo player. They were just going to go as a four-piece. So I met him and played with him at Town Hall in New York City. All we did was tune up and rehearse one song, and then we went right out on stage. I know a lot of people who saw that show. By that time, I was pretty good, and it was probably hard to tell by listening to me that I wasn’t really familiar with all that stuff. I could play pretty well without making mistakes. Peter Wernick and David Grisman were in that audience, I think, because they were going to college there at the time. And then [Bill] offered me a steady job, because he didn’t have a steady banjo player. It was in the wintertime, and he must have lost two musicians just prior to that. He had a lot of people in Nashville that could play with him when he played the Grand Ole Opry or went on the road, but he offered me a job in the fall of ‘62, and I waited until the February of ‘63 before I decided. I thought, well, I ought to go down and see if I make the grade. But when I got down there, he still needed this lead singer and guitar player worse than anything, and he wanted me to try out doing that. So that’s what I did, and I never went to playing banjo since! It’s the craziest thing to change right in the middle.

What was it like to work for Bill Monroe?

I enjoyed it. I was single then, and it probably didn’t matter all that much that I was gone all the time. People said he was hard to work for, but I didn’t find him that way. I’ll tell you the way he was; he was a man of few words. He never said much. If you got on stage and you worked hard, and he could tell you were working with him, he wouldn’t say anything to you. But if he found someone he thought was lazy, oh, he would ride him! I got along good with him, and I learned a lot about what you have to do on stage to keep it going and entertain the people.

Was it difficult to leave his band?

Yes, it was in a way. I was offered a job in California with a bluegrass band that had a TV show in Huntington Park, which is just in the suburbs of L.A. So me and the fiddle player that were playing with Bill quit and went out there. I got married and moved to California. We were young, and you do foolish things sometimes. I should have stayed longer, I know. But things work out for the best usually. I missed playing with him. He trained a lot of musicians. He didn’t teach them; they just came in the band, and they learned from example. He was not a good teacher as far as sitting down and telling you to do something in a certain way. He just got out of you what was in you, whatever that was.

It must be gratifying that today you’re carrying on his tradition?

Yeah, it is, really. He’s the one that got this mess going. I didn’t really think of that in the earlier years, but now that I know a lot of people look up to me, it’s gratifying.

So what have you been working on lately?

What we’re in the middle of right now is a record called Fifty Songs for Fifty Years, because they say I’ve been doing this for 50 years now. We’re recording songs from the ‘60s, like ten songs from each decade. We’re just about done. We’ve recorded 35 songs so far, and I own some of the later ones, so I don’t have to re-record them. It will come out as a 50-song CD set.

Does it seem like you’ve been playing bluegrass for 50 years?

No, it don’t. It seems like maybe two. [Laughs] Time flies after you hit 21, don’t it? I’m telling you, I’m just wondering where all the years went. But it don’t seem like 50 years.

Could you have ever imagined playing for 50 years when you started out?

No. When I started out, I didn’t even think about playing professionally. I just played when I was young because I really loved music. I was really bashful about getting in front of an audience. I just liked the sound of music, and that’s why I learned to play it. Once I learned to play and got a chance to play banjo, they wanted me to play, and it was a nerve-wracking thing to play or sing. I eventually got over that, and I thought, well, I guess you do have to get over this if you want to play music the rest of your life. That’s what happened. I’d rather play music than eat or sleep back in those days. It has worn off a little bit, but I’m 69 now. My interest has waned a little bit, but I still love to get up there and entertain people.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.