Jackson Browne is talking about hope. For the longtime activist and songwriter who’s plumbed the depths of the human heart for half a century with classic albums Late for the Sky, For Everyman and I’m Alive, as well as shimmering ballads “In the Shape of a Heart,” “For A Dancer” and “Sky Blue and Black,” the normalized rage and hatred in today’s America hasn’t extinguished his faith in a better world.

Videos by American Songwriter

“I think it’s built into the human experience and certainly built into the act of songwriting for me,” offers the eternally youthful artist, speaking on the phone from his home in Southern California. “It’s essential for the song actually, that there be some point to have written it.

“Maybe I’m willing to embrace doubt or sorrow, but there has to be some point. That process of writing is generally an excavation of that. And I look for that, it’s just part of my nature. It’s like that song ‘Love Is Love’ (his track on Let The Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit, Vol. 1) has that line – I certainly didn’t write, but I quote them – the Haitians, who say, ‘L’espoir fait vivre.’ You can say it in English as ‘Hope makes life possible.’ Or you can just say it as ‘It’s the well-spring that life comes from,’ you know?”

The question is more an invitation than a query, the opportunity to connect through a truth he believes. It is simple, yet profound. It is that essence that defines him.

Haiti. El Salvador. Native American reservations. The oceans. Cuba. Africa. Browne has spent his life showing up, taking stock, trying to make a difference. All the way back to “Before the Deluge” and mid-career albums Lives in the Balance and World in Motion, he has gently pressed into our collective consciousness to try and lift up our awareness. Never one for preaching, but more suggesting or even showing the listener the lessons he wants revealed, even he sometimes grieves for the world we’ve created.

“Hope is continually assailed by circumstances that we’re living through, and I find there are times that I just can’t write at all, so maybe those are the times I can’t find that hope,” he allows, turning the notion over in his head. “I just have such, I’m still trying to wrap my head around the fact that so many people dispute science, that even dispute the tenets of democracy.

“There are the things that you can always grab a hold of, especially with democracy, saying, ‘Well, we’re furthering an ideal. Even if we haven’t reached it, we’re headed in that direction.’ The journey of true thought. That ideal has pretty much been assailed. It’s been attacked pretty regularly.”

The conversation is more philosophical than political. It’s obvious where he stands. He’s exploring the idea that seemingly smart, educated and informed people would let go of basic common sense or the notion of America and American values most people have been raised with. In these sorts of discussions, inspiration has a way of emerging.

“All throughout the history of our country, there are attempts to shut it down or to circumvent it or to gain it. But never so openly and so aggressively as now. The thing is when I look at that – I actually don’t want to give you the title of the song I’m writing now – but it has to do … I shouldn’t talk anymore.”

Browne, 72, remains relentlessly creative. With an album due this spring – featuring the already released chant/rock “Downhill From Everywhere” and a measuring-the-reality-of-the-moment ballad “A Little Soon to Say” – the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer seeks more from whatever the muses will hand him. He laughs a little – at himself as much as the notion of teasing a poor writer – then gently explains, “It’s counterproductive to start quoting songs that aren’t even written. It’s part of life, though. There has to be hope.”

Sifting through the wisdom he’s encountered from ecologists, activists, nurses, doctors, lawyers, ethnographers and scientists, he lands a little closer to home in trying to pinpoint how someone who’s seen so much of the worst human rights and environmental abuse, selfishness and greed can maintain – and even offer some insight into – his faith.

“Actually my oldest son, Ethan, had told me a few years ago, he said, ‘Dad, this is what humans are good at. We adapt.’ And it’s true. Throughout the history of humankind, there have been a series of circumstances in which they narrowly escape extinction. Now we’re on the verge of self-extinction again, mass extinction. Because we’re causing the extinction of all these other species, so you could say that we’re the, we’re like the meteor striking the earth. We’re like the event that caused the last extinction five or six million years ago, when the meteor struck the earth …”

Browne is not some wide-eyed hippie, spewing notions about macrobiotic snacks. It’s just the tip of what’s inside the mind and heart of Browne, who first found prominence with “Doctor, My Eyes” from his 1972 self-titled debut, as well as co-writing the Eagles ubiquitous “Take It Easy.”

With For Everyman, Late for the Sky and The Pretender, the latter containing the hit “Here Come Those Tears Again,” he defined West Coast singer/songwriter at a time when California country rock dominated rock radio. With Running on Empty, recorded on the road, backstage, onstage and in hotels along the way, Browne’s song cycle relinquished studio gloss for a visceral immediacy that remains the ultimate sonic distillation of rock ’n’ roll life on tour.

Managing to thread social awareness into his deeply romantic, often yearning songs, this ethos defined his albums going forward. Sometimes terse and rocking, sometimes acoustic or world music-leaning, sensitive souls from the ’80s, ’90s and ’00s have used Browne as an emotional and moral compass.

But other than for informing better creative decisions, the man who once backed Germanic chanteuse/Velvet Underground cohort Nico as a teenager isn’t one to live on the glories of the past. Perhaps it is the notion that proper growth comes only from looking ahead, or maybe the idea that inspiration is a forward-propelling commodity.

He talks about a small, framed print presented to him by the 826LA project, a nonprofit founded by author Dave Eggers to help immerse inner city kids in literacy by moving them beyond reading and into writing. By making words an active pursuit instead of passively ingesting them, the volunteers see a whole other kind of engagement from the young people in the program.

“It’s a little framed Celtic design that says: ‘Write The Future,’” Browne explains. “They gave it to me as a little gift. And I just think of myself on the same level as those kids who are trying to imagine something going forward and trying to create it. In my writing, I’m looking for something, and you don’t know till you find it what it is, you know? So (writing) is like consulting an oracle. It’s a way of excavating the present to find out what may be influencing the present and forming the future.

“You hear something that makes sense, a connection that is not necessarily frontal lobe, you know?” he suggests rhetorically. “It’s just something that happens internally. You begin to feel and see the world around you differently. I think that’s the way music affects us, all kinds of songs that I’ve loved, some for 20 years, and then one day, you go, ‘Oh!’ It’s like you’re hearing it for the first time …

“Dylan songs are like that for me. When I first heard ‘Like a Rolling Stone,’ I was too young to get it. When you wake up in the middle of a different period of your life and are hearing a song you know by heart as if you’re hearing it for the first time, that’s awesome. It says the song’s working on more than the most obvious level.”

As his process, next record and overall creativity are further unpacked, Browne suggests, “It’s about seeking … in the end, you want to examine your own desire, what it is that you want. In fact, as a writer, that’s a sure thing, my kind of go-to implement. The thing that’s most reliable to break up the block is to ask yourself, ‘What do you want?’”

For the citizen of the world who has never won a Grammy, it is not about the tangible. He creates to sort his own world, but he also offers insight and compassion into others’ worlds. He borrows notions, absorbs influences, travels to places like Barcelona, Haiti and Africa to savor the world beyond his life. Part of it is trusting the muse.

“I like imagery and language,” he explains. “The thing about music is that, as David Lindley always says, ‘It’s supposed to sound good.’ And the thing I thought was a sort of cryptic and somewhat sarcastic answer was what Bob Dylan said. He said he ‘just tries to think up words that sound good.’ Because clearly people wanted to know how the fuck he knew what to say, to say so much, with so few words. And that cryptic answer actually turns out to be key.

“You do look for words that sound good when you say them, or that mean something that you might not even be sure what they mean. There’s a lot of that in American music, and you know, that’s why we can really love a song that doesn’t make any sense.”

He has also come to trust his process, recognizing the blessing of having both a fairly stable touring band and the ability to call the best musicians in the world to help construct his albums. If not schizophrenic, there is a rhythm to his madness: a live band record, usually followed by a call-in-the-all-stars project.

“We always learn something you didn’t realize you didn’t know, and now you know it,” he begins, explaining the gift of casting an album. “You get something from working with someone, you learn by calling up some legendary bass player or drummer. You learn where your song fits in, where your writing plugs into the mainframe of American music and other music that you’ve heard.

“The band I had on Late for the Sky was not only Lindley, this incredible multi-instrumentalist who played violin, electric guitar, slide, electric slide guitar, but I had Jai Winding, who if I played piano, he would play organ. Some of my favorite parts of that happened between the organ and piano, and the way the chords got played because of my super simple piano playing.

“At the same time, (on Sky) if I was going to play guitar, he would move from organ to piano, and there would be the kind of piano playing that’s on ‘Fountain of Sorrow,’ which was such great stuff. Still, there would be the five people, the basic band.

“For Everyman was that kind of a record, and the third record, Late for the Sky, was the band of five pieces, then the next album was getting back to the best of everyone you can think of. You wind up playing with (Little Feat keyboardist) Billy Payne, and (drummers) Jeff Porcaro and Jim Gordon and (percussionist) Michael Utley. All these great players provide an incredible education.”

And then there’s this next record.

“This album that’s coming this spring was kind of a little of both. I have a band I’m nurturing to be my go-to band, but at the same time, I got to work with Jay Bellerose and Jen Condos. Jen had played on ‘For America’ on my Lives in the Balance. And it was great to get to play with Russell (Kunkel) and Bob (Glaub), and also Mark Goldenberg, who was in my band for seven years.

“Mark came up with some of the best guitar solos ever. The solo on ‘I’m Alive,’ stuff that – basically I encourage people to really inhabit the song themselves – but really, you might as well just go play Mark solo on that song because that’s what makes the song work.”

Those iconic solos – Lindley vocally on “Stay” from Running on Empty, burning wide open on “Redneck Friend” and “Take It Easy” from For Everyman – are part of the musical imprint Browne leaves in addition to the imagery and emotional transparency of his lyrics. Even his later albums – Time the Conqueror, Standing in the Breach – offer a sense that seeking can be a fulfilling way to live. To find the joy, the intrigue, the moments where you feel most alive inform the doubt, the falter that makes the quest satisfying.

Grace Potter, his dear friend, understands. “Jackson’s songwriting is like a beautifully built home,” she says. “No matter what kind of twists and turns life takes, your life is always enhanced when you’re in that space.”

Joking that his album covers could now look like Picasso’s The Old Guitarist painting, he makes sure the reference to the cubist man wrapped around a guitar isn’t lost on the other end of the phone. Obviously not that old or that fragmented, he honors the passage of years and the knowledge he has accrued during his life and his musical journey.

“The truth is that it’s all temporary. Loss in everything that we love is very ephemeral, very true,” he reflects. “I just lost a very, very dear friend a month or so ago. He was a Buddhist and an incredible photographer, filmmaker, flamenco aficionado and an all-around creative person. And he would always say, ‘Impermanence.’ You know, he just relegated it to his own life, to our own lives. As much loss as we experience loving and being alive, we’re doomed, fucking doomed. It all has to come to an end.

“That’s the other thing most songs are about – most songs are about freedom. Many are about impermanence. And putting those things together? To me, that’s where the beauty is.”

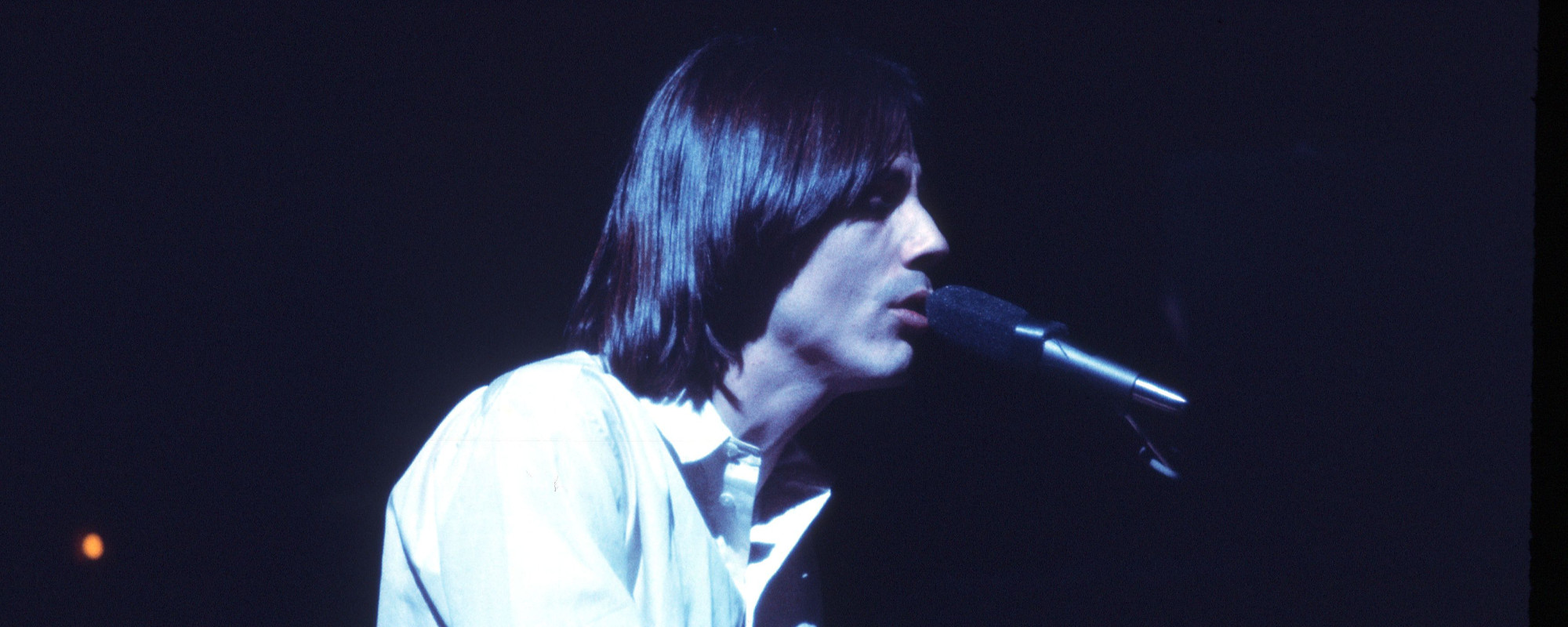

Photo Credit Nels Israelson

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.