“I hadn’t thought of myself, because I was so busy writing for others,” says Albert Hammond on what led to writing his first new music in nearly 20 years, Body of Work. “I didn’t think of myself until the day that I did. Then I said, ‘I’m just going to write the best for me. Save the best for last.’”

Speaking from his home on the southern coast of Spain where he grew up in Gibraltar, Hammond is nearly three months shy of his 80th birthday but isn’t literal when it comes to the end of his career. His has spanned more than six decades with hits from The Hollies’ “The Air That I Breathe,” Julio Iglesias and Willie Nelson‘s 1982 duet “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before,” Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” and Leo Sayer’s 1977 No. 1 “When I Need You,” among more chart toppers.

Writing earlier songs with Mike Hazlewood, from his 1972 debut It Never Rains in Southern California and hit title track, Hammond’s decades-long collaborations stretch across work with Hal David, Diane Warren, Carole Bayer Sager, Holly Knight, and more. For Body of Work, produced by Mathias Roska and recorded at the famed Hansa Studios in Berlin, Germany, Hammond reunited with another old friend and longtime collaborator John Bettis. The two co-wrote Whitney Houston’s 1988 hit “One Moment in Time,” which won an Emmy and was used for the 1988 Summer Olympics, along with Diana Ross’ “When You Tell Me That You Love Me” from 1991.

Videos by American Songwriter

[RELATED: Behind Starship’s Final Hit with Grace Slick “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now”]

Wrapping his thoughts around Body of Work, his first collection of new material since Revolution of the Heart in 2005, Hammond crosses mortality, the socio-political, and the nostalgic with lost loves (“Bella Blue”), and recurring themes of war and its torn remnants (“Young Llewelyn”). Hammond’s gravelly vocals reveal a life’s worth of more stories he was determined to get out, from opening Neil Diamond-tuned “Don’t Bother Me Babe” and Americana and reggae-tipped “Shake a Bone” and one of many life meditations on Body of Work: No other day was like the day ahead / No second chances when you’re cold and dead…The music’s everywhere / once you think that you can dance.

“You think you’re gonna save the world,” says Hammond of the acoustic-chugged “Gonna Save the World” singing All you really know is follow who you really are…nobody has the magic words.

Crisscrossing genres in Body of Work, Hammond delivers the pop-bent “Looking Back” while keeping his reflective angles. Every road you travel runs both ways…there’s so much more to life than waiting around to die, Hammond sings on “Both Ways,” while “Knocking On Your Door,” has him crooning of forgiveness: I was never much for talking / I was just getting by. By its halfway point, “Let It Go” highlights one of Hammond’s most moving ballads, colored by some of his personal struggles.

Body of Work is just one more specimen of Hammond’s lyrical mastery, which has always revealed what it feels like to be human. Penetrated by real-life events, some of the songs are reflections of Hammond’s divorce from his wife Claudia of nearly 40 years in 2017 to fighting an autoimmune disease and vocal atrophy, and more.

“It just relates so much to my life now,” Hammond tells American Songwriter of Body of Work. “I’m going to be 80 in May. My body of work is part of my life. It’s my 80 years in this world, of what I perceived, what I’ve learned, and what I felt. And there’s nothing better than to write about it because you can get it off your chest.”

Hammond spoke to American Songwriter about the making of Body of Work, the rainy story behind his 1972 solo hit “It Never Rains in Southern California,” and why he isn’t ready to stop now.

American Songwriter: You said you saved the “Best for Last” with Body of Work. Is this album, in fact, your final album?

Albert Hammond: No. I have so many ideas in me. I was playing the piano this morning, and I was singing You make me feel like a brand new man, and I thought “That’s a great idea.” Mostly, it comes like that—whenever it comes. I don’t sit down every day to write. I have to connect to something.

I feel like I connect and then energy builds up inside me and it just wants to explode. Sometimes I spend a week or two, just putting things down every day, but I never sit down and finish something. If you sit just for one, then you lose that energy of when it first comes to you, which is most important. It could be 30 seconds or a minute. When you don’t have a project, that’s what happens, and then when you have a project, obviously the energy rises to another level.

AS: All of the tracks on Body of Work are new. What ultimately led you to these songs?

AH: With this album, I went through seven or eight years of not a good time. I went through a divorce and the pandemic, an immune disease, then vocal atrophy. That’s how “Let it Go” came up because I just kept saying every day, “Let it go.” And it’s still going on. There are still things happening that are uncomfortable. I just felt I had to get this weight off my shoulders.

The best way is to write about it, so I called a songwriter friend of mine [John Bettis], who I love working with, and I love talking to. He’s around a year or so younger, but we relate. You know when you have someone that you really like to have a coffee with because it’s easy to talk to them. It’s a nice relationship. It isn’t about “Oh, I’ll come over for two hours, write a song,” and then I don’t see the person for a month or a year or whatever.

I’d go in and demo them [the songs] with just my guitar. I’d put the mic in the middle of the studio and just sing. We wrote for a while and collected 38 or 40 songs. Some of the ones that I left out are really great songs, but you can’t put out a record with 30 or 40 songs.

AS: You can always release a double album.

AH: (Laughs) Yes, it was a double album. Then I went to Nashville and I looked for a band that plays together a lot like the Wrecking Crew, which was what I used in the ’70s when I first went to LA. It all seemed to connect. Even now when people call me and say they love the album, it makes me feel like it was worth it. Whatever the weight on my shoulders was, whatever I went through, was worth it.

AS: Some songwriters who have been working as long as you have admitted that it’s often hard to keep pulling from within to find those stories.

AH: I first pulled from within, because it’s a new thing. I’m not looking to make an album of things that I did before. If one day, I write five new things, and I gotta fill up an album, I might listen back to something to see if it relates. Normally, I would start from scratch because it’s your life, isn’t it? Whether it’s love or whether it’s politics or whatever it is in the song, it’s what’s going on now in my life.

AS: Whether it’s a song you wrote for another artist or your first hit “It Never Rains in Southern California” in 1972, what is your connection to some of those songs from your past?

AH: There’s always a connection. “It Never Rains in Southern California” is strange. I was going to write a song with my old partner, Mike Hazelwood, whom I wrote songs with in the ’60s and early ’70s. The day before, I was just messing around with an upright piano in a spare room where I lived in Rainham, Essex (England). I was going to write with Mike the next day and I had this tune. I didn’t have a title, and I went to Fulham where he lived in London on this miserable rainy day. I get to his place, and I’m all wet. He handed me a towel and asked if I’d like a cup of tea. So he goes to the kitchen to make a cup of tea and I walk into his living room and pick up the guitar. I didn’t even remember the tune and I looked up at this library of books and one of them read “The Railways of Southern California.” And I just started to sing (singing) on the railways of Southern California. And he said, “Did you say ‘It never rains in Southern California.” And I said, “No, but that’s great,” and that’s how the song came about.

I had never been to California. It was written on a rainy day in London in 1969, and we based it on my time in Spain when I was down and out trying to make it, and I would tell my parents how great things were going so they wouldn’t come pick me up, because I was just a kid. I played it to Glen Campbell. I played it to The Seekers. Everyone told me it was a terrible song.

AS: When did you know it was finally ready?

AH: It waited from 1969 till 1972 when I did an audition for Clive Davis at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I never played the song, because I was told it was such a terrible song, and Clive happened to say to me, “I love everything, go to the studio, but do you have any other songs?” I said, “I have one more, but I never played it to anyone because they told me it was a bad song.” I played it for him and he said, “That’s going to be your single, and that’s going to be the title of the album, and it probably will be your biggest single.”

[RELATED: The 25 Best Clive Davis Quotes]

So you see, when you believe in a song, or when the song believes it should be alive, it’ll wait and wait. But it will be there waiting for you to make that decision—or for someone to come and say, “You know that song that nobody likes that I’ve never heard?” It’s a connection.

People say to me, “What’s your favorite song?” They’re like your kids. They’re not the same. It’s just a beautiful thing to be able to create something out of nothing and be different all the time. I still connect to my first hit in 1968 [“Little Arrows” by Leapy Lee]. I still play it when I do something live because the songs—they last.

AS: What is your connection to the 17 songs on Body of Work now?

AH: They all fit with each other. When I was making the album, it felt a bit like [The Beatles’] The White Album, because there was such a difference in songs from “Bella Blue,” such a sad story about a woman who falls in love with a man. He goes to war, they marry but he never comes back. It’s a sad song but it relates to what’s going on today. When I was writing this, I could see Eastern Europe, and I could see this woman feeding the pigeons. When she died and met up with her husband in heaven or wherever the pigeons still went back to the parkway and waited to be fed. It’s such a beautiful story.

Another song “Young Llewelyn” [was written] without talking about the war today and what’s going on in the world today. We took something that happened a couple of centuries ago. The British kept stealing the land from the Welsh and young Llewelyn tried to get rid of them and take the land back. Even though it was a couple of centuries ago, it’s still going on today. We haven’t learned anything, have we?

AS: It sounds like you’re far from being done writing. There are so many more stories.

AH: After I finished a Body of Work, I started working on a Christmas album in November. As a singer and songwriter, I think every artist should do a Christmas album. I wrote two new songs and then chose some classics, some hymns—things that I would sing and in church when I was a choir boy. There are some songs that brought a tear to my eye, but I did them my way, the way I would like to hear them. They have a little more rock. Some have a country-folk feel, and I used an amateur children’s choir from Gibraltar.

I also have material for another record, but I want to write new things. You get to an age where you start to say, “I’d like a bit of this and a bit of that” so maybe I can put it on something that will last longer than me, which is a record because a record will be around forever.

There’s going to be more. I guarantee that. As long as I stay healthy, there’s no doubt.

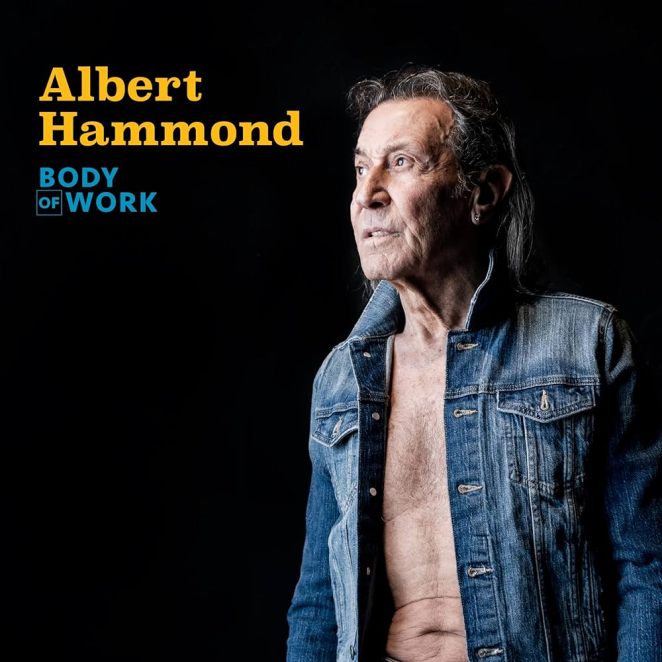

Photos: Rita Carmo / Courtesy of Vicious Kid PR