Pete Seeger was a major figure in America’s folk revival and influenced generations of musicians—including Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and Billy Bragg.

Videos by American Songwriter

Before dedicating his life to music, Seeger wanted to be a journalist. He studied at Harvard, where he started a radical newspaper. Then, he joined the Young Communist League at age 17. In 1938, Seeger dropped out and returned to his hometown, New York City, where folklorist Alan Lomax helped him find a job cataloging and transcribing folk music.

After a run of hits with The Weavers in the early 1950s, the quartet joined an extensive collection of performers who were blacklisted because of suspected Communist ties during the McCarthy era.

He later returned to performing solo concerts and built an audience of young folk music fans. Soon, Seeger recorded for the Folkways label and helped found the Newport Folk Festival in 1959.

Seeger’s rendition of “We Shall Overcome” became a civil rights anthem in 1963. Adapted from “We Will Overcome,” Seeger had changed “will” to “shall.” (It’s based on a much older hymn called “I’ll Overcome,” sung by striking tobacco workers in South Carolina.)

Additionally, he helped keep folk music alive with a collection of reworked standards and original compositions, at times blurring the lines between the traditional and his originals.

Below are five classics to celebrate one of the great protest singers in American history.

I’d ring out a warning

I’d ring out a love between my brothers and my sisters

All over this land.

“Turn! Turn! Turn!” from The Bitter and the Sweet (1962)

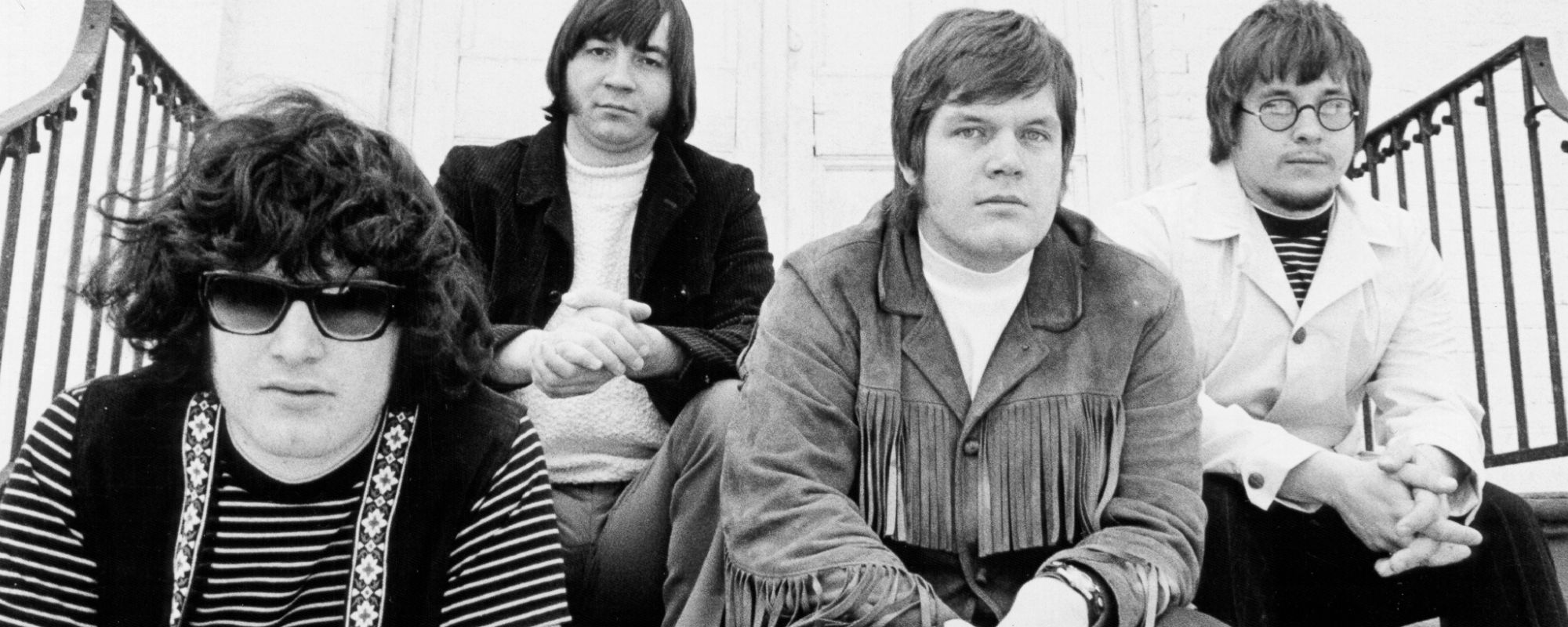

Seeger borrowed from the Book of Ecclesiastes to write one of his signature tunes. But most probably know the version made famous by The Byrds in 1965, which reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 the same year. The Limeliters first released the song in 1962, and Seeger followed with his own recording months later.

“Oh, Susanna” from American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 2 (1958)

Stephen Foster, also known as the Father of American Music, wrote “Oh, Susanna” in 1848. He said the money he received from the song “had the effect of starting me on my present vocation as a songwriter.” It became the first “hit” in American history, and the forty-niners sang it during the California gold rush. Moreover, Seeger’s recording shows the virtuosity that made him a master of the 5-string banjo.

“Little Boxes” from Broadside Ballads, Vol. 2 (1963)

Seeger’s friend, Malvina Reynolds, wrote this middle-class satire in 1962. “Little Boxes” describes a homogenized suburbia where sameness feels like a virtue. Reynolds was inspired after witnessing developing neighborhoods in Daly City, California, a suburb of San Francisco. Her song also introduced the word ticky-tacky—a reference to the cheap materials used to build tract housing. However, Tom Lehrer described “Little Boxes” as “the most sanctimonious song ever written.”

“Solidarity Forever” (1955)

Put to the tune of “John Brown’s Body,” the same abolitionist marching song that inspired “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Ralph Chaplin crafted his worker’s anthem in 1915. Three years earlier, he was working as a journalist covering striking coal miners in West Virginia. It inspired his rallying cry for union workers. Seeger helped popularize Chaplin’s labor song, which turns 110 years old this year.

“Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” (1955)

Seeger and co-writer Joe Hickerson adapted the lyrics to “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” from a folk song called “Koloda-Duda,” which appears in Chapter 3 of Mikhail Sholokhov’s novel And Quiet Flows the Don. The words are sung to a slowed version of an Irish lumberjack melody. They describe a cycle of girls picking flowers, men choosing girls, and then becoming soldiers who die in war before ending up in graveyards covered in flowers.

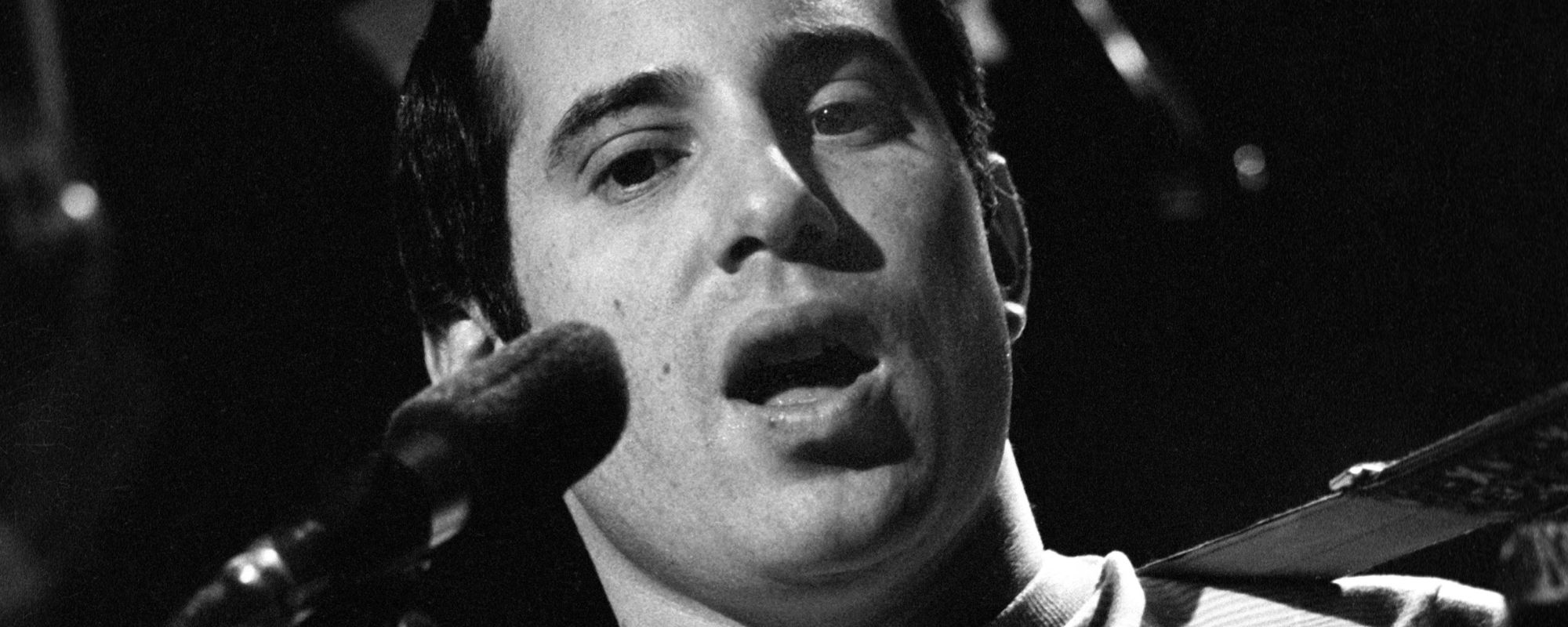

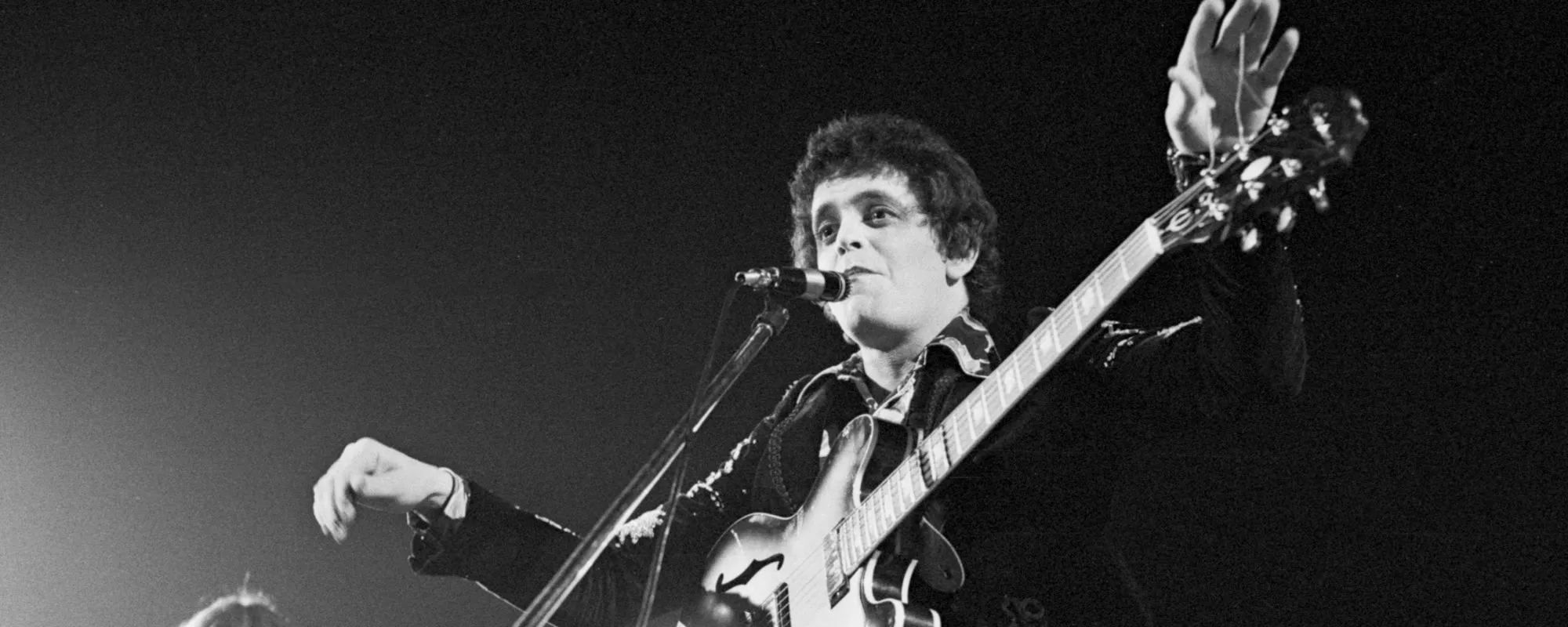

Photo by Brian Shuel/Redferns

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.