Videos by American Songwriter

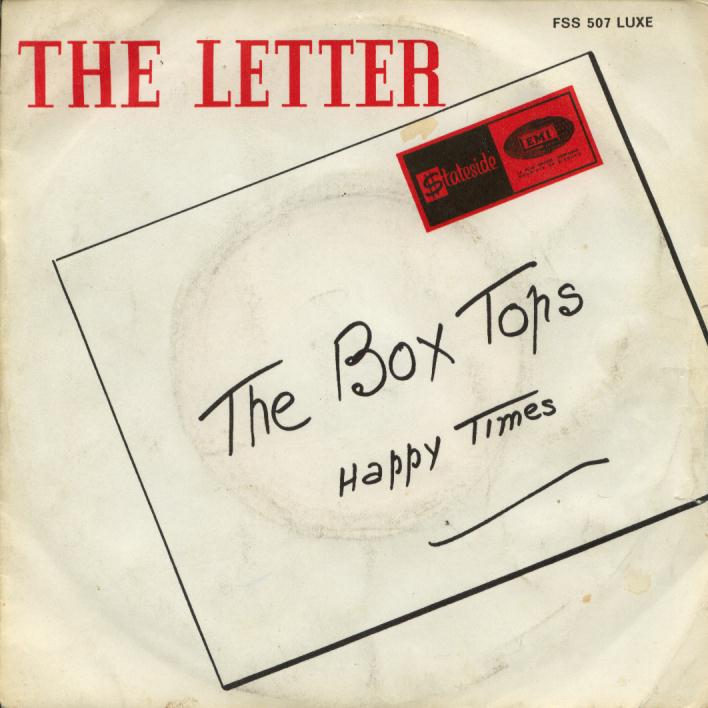

“The Letter”

Written by Wayne Carson

Some years back I attended a party where a number of former employees of Bell Records were present. During the late 1960s Bell had set itself up as a sort of mini-Atlantic, releasing some of the tastiest fruits of the southern soul harvest before moving into MOR pop in the 1970s. I was the sole outsider at the party, so my presence did not exactly inspire a fount of revelations (when these people die, I remember thinking, they’ll take a lot of secrets with them), but one topic that did arise was the question of “best” project ever released by the label. One person suggested the original cast recording of Godspell, the 1971 Broadway musical. In my experience talking with record company people, “best” usually means most commercially successful, so in this respect the choice of Godspell was no surprise. But, I thought, what about such masterpieces of soul as the original “Dark End of the Street” (released on a label Bell distributed, Goldwax) or James and Bobby Purify’s “I’m Your Puppet”? If, as an observer once suggested, Bell specialized in picking up Atlantic’s leftovers, it only proved how soul music in the late 1960s was a giant banquet, with more than enough delicacies to go around.

One of Bell’s choicest morsels arrived with “The Letter,” a moody opus by the Box Tops that shot all the way to No. 1 on the pop charts in the summer of 1967 (and is still recognizable for its first line: “give me a ticket for an aer-o-plane, ain’t got time to take a fast train”). Led by a startlingly gravel-voiced teenager, Alex Chilton, the Box Tops formed in Memphis and had scarcely gotten past the talent-show phase when they arrived at Chips Moman’s American Sound Studio at 827 Thomas Street in their hometown. What made the session for “The Letter” different, aside from the evident quality of Wayne Carson Thompson’s song, was that it would be the first one overseen completely by Dan Penn, a 26-year-old songwriter with an almost preternatural talent for mining old-soul verities of the heart. Like Chilton, Penn was something of an oddity; it’s likely that, on some level, each young man responded to this same quality within the other, in a way that made a partnership soar. According to an interview in Robert Gordon’s excellent 1995 book, It Came from Memphis, Penn advised the young singer on a few points (“told him to say ‘aer-o-plane,’ told him to get a little gruff”) and otherwise let him be. Chilton, for his part, had come from a somewhat rarefied background: his mother owned a respected art gallery; his father was a jazz pianist. In time, he would be destined for what many critics have regarded as greater things, as leader of the influential 1970s band Big Star and as an iconoclastic musical force in his own right. For now, “The Letter,” sparked by a clever “airplane engine” sound effect on the coda (which Penn has claimed he had to fight studio owner Moman to keep), would take off to become one of the standout hits of the 1960s, an AM radio staple that continues to be heard today. Like many great records, not one element—from the arrangement to the vocal to the instrumentation—seems out of place. It goes down in (barely) two digestible minutes, as satisfyingly perfect as a shot of Johnnie Walker.

As it turned out, The Box Tops would perform on “The Letter,” along with one or two other numbers, and not much else. Most of the later releases sporting the band’s name (including the marvelous “Cry Like a Baby” and an interesting 1969 album, Dimensions) were Chilton recordings backed with the American Studio house band. Supposedly, Moman felt more comfortable using his own musicians, an ace team that included guitarist Reggie Young and drummer Gene Chrisman (at American, they would provide the backing for hits by Neil Diamond, Wilson Pickett, Elvis Presley and many others). Speaking to Gordon, Box Tops member John Evans confessed his disappointment: “Put yourself in my place. A 19-year-old kid, you finally get a chance to do something you’ve wanted to do for years, it ends up being number one in the country for an entire year. Does it even seem reasonable, much less fair that we can’t play on our records?”

When I saw in the paper recently that Alex Chilton had died at a too-young 59, my thoughts went back to that party of Bell alumni, few of whom seemed to recognize the greatness of what their label had produced during those fecund late-60s years. A search on Google maps reveals that the American studio at 827 Thomas Street in Memphis is gone too, replaced by a gas station. The fruits of our culture survive while the tree suffers neglect: next time you see a 45-RPM copy of “The Letter” at a thrift shop, buy it; along with its digitalized descendants, it will open a window into a rich musical world, the creators of which are disappearing without fanfare.

Definitive Version:

Honorable Mentions:

One Comment

Leave a Reply