“They always say, with artists, that the secret of making good art is to know when to stop,” says Lene Lovich from her home in Leicester, England. At the moment, Lovich has been contemplating quite a few things, but putting an end to what she started, musically, in the mid-1970s isn’t on her agenda yet, and not after completing the Cosmic De-Evolution Tour with Devo and the B-52s in 2025, with more dates set in the UK and Europe for 2026.

The tour, her first in North America in 35 years, was natural since Lovich has a decades-long connection to both bands. She first toured with Devo on their Be Stiff Tour and also covered the band’s song of the same name. By the late ’80s, Lovich went on tour with the B-52s three times and played two benefit concerts with the band supporting People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) in Washington, D.C., in 1988 and the second a year later in New York City.

“We were all starting out at the same time,” Lovich says of their earlier beginnings during the early to mid-1970s. “I think they [Devo, the B-52s] didn’t want anybody to be too much the same. We are all different, but we’re all equally interesting in a fun sort of way.”

Experimental, theatrical, post-punk, avant garde—there was never a single genre worthy of her musical craftings, but Lovich often slipped into the New Wave category from her 1978 debut Stateless and single “Lucky Number,” which went to No. 3 in the UK through Flex (1980), No Man’s Land (1982), and March (1989). After a lengthy hiatus, Lovich returned with her fifth album, Shadows and Dust, in 2005.

By the late ‘70s, Lovich even topped the U.S. disco/dance charts with an environmental uprising song, Cerrone’s “Supernature,” co-written with the French artist and songwriter Alain Wisniak. And though she’s the first to say she’s “not very good” at collaborations, Lovich has had some memorable unions. Along with her longtime co-writer, bandmate, and partner Les Chappell, Lovich also co-wrote the Flex tracks “What Will I Do Without You?” and “You Can’t Kill Me” with Judge Smith and worked with British songwriter, producer and photographer Morgan King on “Retrospective” in 2018.

Thomas Dolby also wrote and played keyboards on Lovich’s 1981 dance hit “New Toy,” which peaked at No. 19 in the U.S.; both also shared a surprise performance together live during her 2025 tour.

Videos by American Songwriter

In 1986, her animal rights anthem, “Don’t Kill the Animals,” with Nina Hagen (who also covered Lovich’s “Lucky Number” in German), also delivered a powerful message, long before Dolly Parton, Paul McCartney, Loretta Lynn, Prince, Morrissey, Chrissie Hynde, P!nk, the Black Keys, and others stood behind PETA. Hagen and Lovich were the first artists to donate a song to the organization, singing Life is for living—the animals agree / If they were meant to be eaten they’d be growing on trees.

Though Lovich, now 76, hasn’t released another album since Shadows and Dust, she continues touring and released the box set Toy Box: The Stiff Years (1978-1983), a compilation of songs from her years with the label, in 2023.

Back home in the UK, Lovich talked about playing in North America after nearly four decades, an impromptu meeting during her art school days in the early 1970s with Surrealist artist Salvador Dali, and the possibility (or impossibility) of making new music now.

The Cosmic De-Evolution Tour with Devo and the B-52s was your first time in the U.S. in 35 years. Why did so much time pass before you returned?

I don’t have a very good sense of time as a person. If I’m thinking of things, I can lose track of time. If you’re somebody who has lots of ideas in your head and gets easily distracted, you can lose track of time. And that’s not a bad thing. I would come over all the time in the early days. Back in the ’80s, we were in America a lot, and it was never a problem. It was a very exciting time, because there was a real mix of creative styles, and it was a great time.

When I’m playing with the B-52s and Devo, the performance is quite short and there’s not much time to go on any journeys this way. You really just have to concentrate on maybe the songs that you think people would like to hear. There’s quite a lot from the first album. I like all my songs. I’ll never get tired of any of them.

It’s great to hear that you still have a connection to your older songs.

Totally, because they were all genuine, important songs for me. There are no throwaway songs. And even songs that were not mine, I had an affinity with, so there’s no reason to stop doing them. I think it’s also because I haven’t changed so much as a person. Even though I’ve had lots of experiences, I’ve always had a very strong connection with my mind and my ideas, so I’m still happy to be surrounded by ideas, whether they’re old or new.

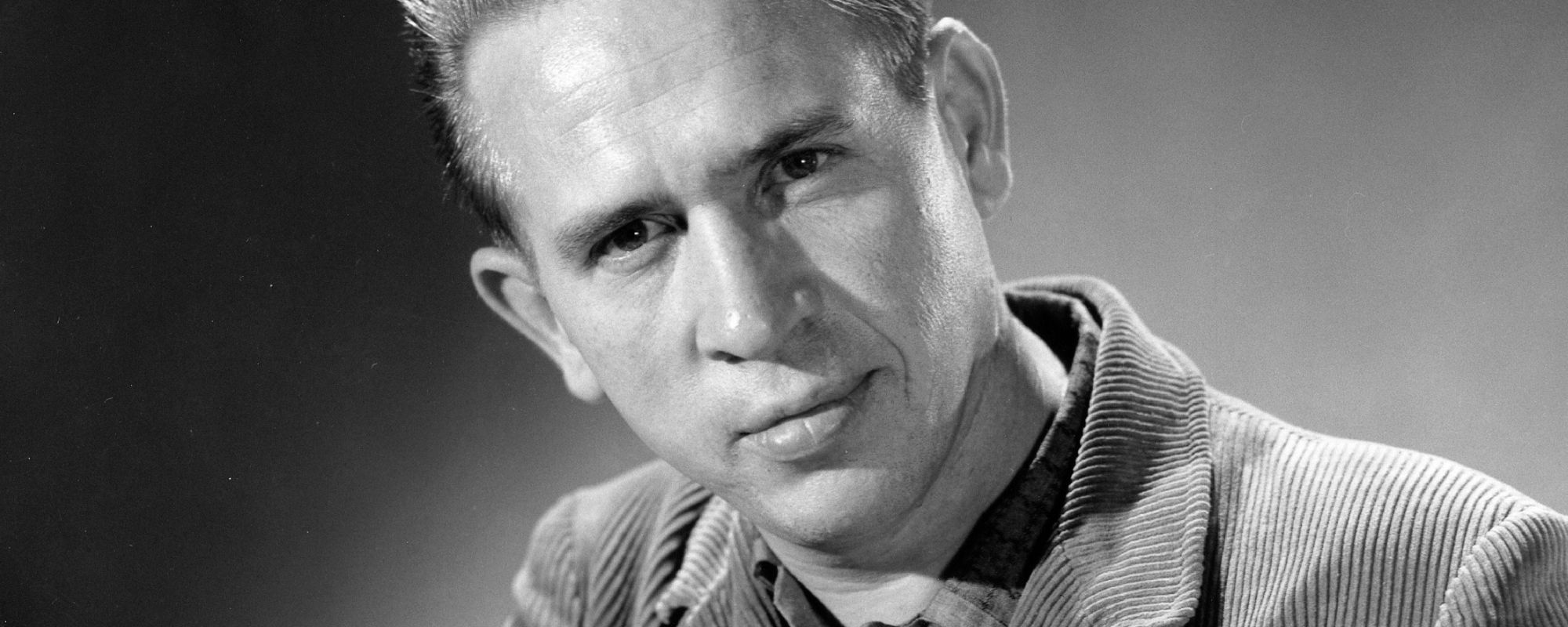

Pam Hogg; (bottom) Lene Lovich

(Photo: Kate Garner)

So many artists are often swayed. How did you manage not to change?

I went to art school because I thought that would be a place of freedom and happiness, where you could try all kinds of ideas. Maybe it’s better now, but when I was at art school, it was very disappointing. My ideas were not encouraged, so I spent a lot of time being sad, and then I thought, “Well, I think I need to make things better.” So I spent a lot of out of art school and teaching myself. I was very interested in three-dimensional work, so I would make my own things at home. I did go to art school enough, but it was not really a happy place for me, and it made me realize that my ideas are very important—and that I like my ideas—so I had to go my own way.

People talk a lot about their career and being popular and having a hit record, but none of those things were really that important to me. I just wanted to connect with my ideas, and I wanted to learn a bit more about myself, try things and not have to explain myself.

People talk a lot about their career and being popular and having a hit record, but none of those things were really that important to me. I just wanted to connect with my ideas, and I wanted to learn a bit more about myself.

Lene Lovich

While attedning art school in London (Central School of Art and Design), you made a pilgrimage to Spain to find Salvador Dali. How was your meeting with him?

I was having such a bad time at art school, and wanted to make art from mental images. Then I discovered this thing called Surrealism, and it’s all about mental images. And I thought, “There’s got to be some magic in this. I need to find out about it.” So basically, I stalked him. I found out where he lived. I was too scared to knock on the door, so I just hung around outside, and he eventually came out. And so then we met.

It was a really great feeling, because we didn’t say very much, and he was only speaking a bit of French, and I only understood a little. Then I thought, “I need to do this. I’m going to knock on the door.” I went back a couple of days later and knocked on the door, but unfortunately, he didn’t answer. His partner answered the door, and she was not so friendly, so I thought that maybe I was asking too much, and I just went away.

That’s quite a feat, stalking Salvador Dali.

Well, I was very respectful. I didn’t approach him when I saw him coming out of the house. He came towards me. I did not move towards him because I didn’t want to scare him.

Have you been working on anything new since Shadows and Dust?

I’ve just been enjoying playing live. For me, although I like experimenting in the studio and finding new sounds and exploring ideas that way, I think live is probably the thing I like best, so I’ve just been doing lots of performances, mainly in Europe and the UK (2026 UK/Europe tour dates).

Has songwriting changed for you since the early days?

It’s always a mystery how the song happens. The best time, quite often, is when you’re not expecting things to happen. For example, when you first wake up in the morning, and you have that half-awake situation where your mind is not filled with all the daily things that you might be doing. That’s a very precious time when you are really free from all your other worldly activities. And if there’s something that comes into your head at that time, it has quite a strong effect on you.

It makes you take notice. It can be a feeling, or it can be a sound, or it can be just something that you need to explore. They’re all a surprise. It can come from outside myself. It’s not just me thinking of ideas. My mind can be stimulated by hearing people talking from a distance. You hear a noise that they make, and it can make you think of something. A rhythm of somebody’s speech, or even just the rhythm of the cars going by can give you the start of a shape. And if it’s a really strong feeling, you want to carry on with it, and it sort of evolves. I never plan anything. I never say I’m going to sit down and write a song about something particular. I just keep an open mind.

And if the idea is very strong, or if something I’ve heard or seen or experienced in any way has such an effect on me, then I will think about it and play with it until it starts to get stronger. It’s really like an evolution. It grows. It has to have time to evolve.

“Don’t Kill the Animals” had a strong message. Are you drawn now to more politically driven songs?

There’s a kind of magic in making a suggestion that people then go away and have some kind of connection with it or not. I don’t like dictating to people, however, that changed quite dramatically when Nina Hagen came to my house to record [“Don’t Kill the Animals”]. She was very excited about animal rights, and I’ve been a vegetarian for a long time, but she really pushed me off the fence. It was a very exciting time working with Nina.

It was probably the fastest song I’ve ever written. We just sat at the kitchen table one evening and threw ideas down really quickly. For Nina, it was very fresh in her mind the things that she wanted to say, and it was more a realization for me that I had sympathy, but didn’t do anything about it. It was very much in the moment.

Would you do a similar collaboration again?

If it seemed to have a sense of urgency, maybe. If the spirit, the feeling, was right, maybe. But I don’t do that very often. I don’t think that’s my strong point. I think people should learn to live by example and share goodness with other people.

I’m not very good at collaborating because I can’t explain myself. I’ve never been able to express that easily with people, and I find that when I have been in a situation sharing ideas with people, it’s too easy for most people, most musicians, to do what’s normal for them and what’s easy for them. So I don’t always get excited by ideas that I’ve heard before. It’s difficult. You can like the person, but not necessarily like the way they do music.

When you have a lot of ideas and you want to try them all, it can take quite a long time, and that can frustrate other people. That’s another reason why I’m not very good at collaborating.

Are you still friends with Nina?

I don’t have much connection with her now, but it was a very natural, easy friendship. It just seemed like we had a connection and liked each other’s company. We went on tour together, and we found out that what she was good at and what I was good at were very different, which is healthy, because she could do the things that I didn’t like doing and and I could do the things that she didn’t like doing. We had a common goal at the time, so it was very exciting.

Along with touring, what else is next for you now?

I don’t know, because I am getting older and older. I still have a good singing voice, so it makes me think I still want to keep doing this. Maybe there’s a time when I won’t be able to do it, so there’s a lot to think about. We’ll see what happens.

They always say, with artists, that the secret of making good art is to know when to stop.

Photo: Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.