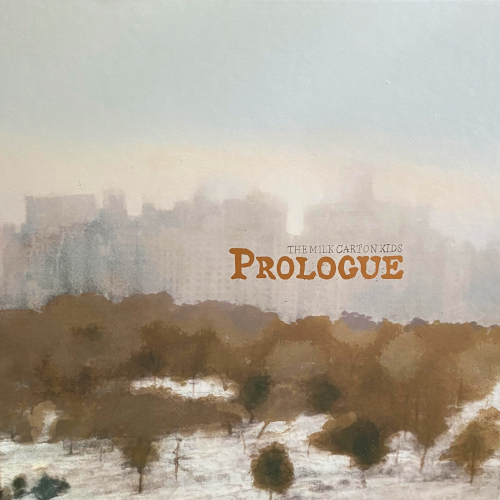

PROLOGUE TO PROLOGUE

Videos by American Songwriter

Written by Kim Reuhl from Milk Carton Kids’ Prologue 10th Anniversary Edition liner notes.

It was a beating-hot day. Heavy sun drew sweat down backs, around necks, like a river cutting a canyon between your shoulder blades.

I made my way through the thick walls of the fort, toward a tent where The Milk Carton Kids were scheduled to play. A knot of folkies stood chatting by the tent and among them I spotted the towering head and black-coated shoulders of Joey Ryan from behind. Next to him, taking up slightly less space, was his bandmate Kenneth Pattengale, also shouldered in black with fashionably disheveled hair. Both were recognizable from a distance in their matching clothes.

Over the fort walls, a mainstage and field crowded with people. Past them, food and merch tents. Farther, Newport Harbor, the Atlantic, beyond.

I felt a pang of pity for Ryan and Pattengale’s underarms, pressed below so much suit and tie, in that heat. But the singer-songwriters seemed jovial enough, ready to take the stage under the shade of the tent. Once at their microphones, they moved through a set of heart-rending originals from Prologue, an album they’d released for free online almost two years earlier, the power of which had landed them a slot at North America’s most storied folk music festival.

It’s hard to believe now, but those were still the days before Spotify’s dominance. Back then, Apple’s music program was a behemoth bit of software you downloaded onto your machine and filled with songs that you had either purchased from their store in MP3 format or uploaded from a CD you had on a shelf in your living room. Exactly how an indie folk band could reify their music for their fans in that moment between the dominance of the tangible and that of the digital, was still somewhat of anyone’s guess. Some artists at the regional Folk Alliance gatherings in those days were selling their music in dozen-song sets on thumb drives. Others were pushing vinyl, which seemed like a comical throwback at the time but has since proven timeless.

The Milk Carton Kids chose to exist in the in-between. They printed CDs, which they sold for actual money at their shows, and a limited run of vinyl. If folks wanted to skip all the paper and plastic, they could download a .zip folder with the MP3s and a PDF of the album art and liners, for free. While many in the music media found this to be somewhat of a gimmick, I found it delightfully folky. The decision to separate music from its own commodification was as rooted in the tradition of “folk” as anything.

After all, the duo’s free-if-you-want-it download of Prologue came a decade after Gillian Welch predicted, “We’re gonna do it anyway, even if it doesn’t pay” on her Time (The Revelator) album. It came a decade before Spotify CEO Daniel Ek suggested artists who want to make a decent living from their music should simply make more of it. As though a song is nothing more than a widget whose production can and should be streamlined.

“We joked to our fans they could ‘choose whichever option they thought correlated to what type of person they thought they were,’” Pattengale remembered. “But, really, we wanted whoever had the desire to listen to be able to do so.”

Joking aside, the decision was a gamble. But a gamble built atop a tradition.

Twenty years earlier, indie-folk icon Ani DiFranco rose to prominence not by selling CDs as much as shucking cassettes that people then copied and passed around dorm rooms. Thus, the sub-corporate, non-dollar-driven distribution of music had already been proven to have legs by the indie folkies who came before. Even they were pulling from a long tradition of bootlegging that boosted the careers of everyone from Bob Dylan to the Grateful Dead—a tradition that was led by fans and eventually became something artists tapped into themselves. The Milk Carton Kids weren’t reinventing the wheel, then, so much as building a new vehicle atop it.

And anyway, not many folkies can say they launched their career and landed on stage at Newport just two summers later. But there they were, in their suits, delivering the heartbreak songs, peppered with their Who’s-On-First-style back-and-forth banter.

“It’s almost like when a song is so sad, you have to have something to make the pill go down, so to speak,” says sad song master Emmylou Harris.

Underpinning it all was The Milk Carton Kids’ quietly devastating lyricism, which they delivered on a bed of Pattengale’s flurried fretwork and Ryan’s well-moored rhythm guitar. People in my profession, prone to drawing comparisons, would drop names in those days like Welch and Rawlings, though I suspect this was primarily because of Ryan and Pattengale’s balanced guitar work. Their vocal performances were more akin to Simon and Garfunkel, their stage banter reminiscent of the Smothers Brothers.

Rosanne Cash recognized the duo as altogether original. “Nobody’s sui generis anymore,” she says. “But Kenneth’s guitar parts veer off into territory that’s not typical of singer-songwriters. He borrows some jazz and classical and roots—it’s dreamlike. As songwriters, sure, they’re part of a tradition. Harmonically, they’re part of a tradition. But that added thing, about choice of notes and melodies, is really original.”

Indeed, considering all that was happening in the recording industry during the demise of MySpace and the rise of Twitter—an atmosphere in which literally anyone could record at home on Garage Band or ProTools and throw their music up for an audience to find—Ryan and Pattengale made a different impression. Though they were clearly a couple of guys in costumes on a stage, they may as well be sitting in the living room, speaking in clear, poetic strokes about how they worry for the future and can’t let go of the past—two themes that have rooted folk music for the past few centuries.

SOME CONTEXT

Though most modern music fans tend to pin folk music’s heyday between 1959 and 1965—when Newport Folk Festival held its first-ever fete and when Bob Dylan brought a rock and roll band to its stage to perform “Like a Rolling Stone,” respectively—actual folk music history exists outside of time.

Folk music purists would tell you that the only true folk song is one that has been around so long, nobody knows where it came from nor how. Melodies have been passed down through a multi-century game of Telephone. Lyrics have been mindfully adjusted by just about everyone who has ever sung them. But the grand story of American folk music—its heroes and legends, its gelatinous shape-shifting evolution from generation to generation—is too transcendent to be held to such pure standards.

Start anywhere you like.

You might be tempted to begin with the arrival of European colonists in the Americas, but their folk songs stretch back across the centuries, culled from their entire continent of origin. Those people’s music married with that of the natives who already lived on the land they claimed for themselves, as well as the music of the enslaved people they dragged across the sea. Over time, the European fiddle met the African banjo and the Arabian guitar. Songs of oppression and freedom, songs of longing and lust, songs of nonsense and deep romantic love were passed down and altered until they seemed like different songs entirely.

Civilization spread, wars came and went, economies rose and fell. Whatever the context or story, people sang and played with whatever and whomever they could find. Sometime during the 20th century, as a new recording industry emerged, scholars went afield to collect songs and record them. They called the songs they found “folk songs” because they came from the folk. But these included blues, rags, dirges, hymns, love songs, hillbilly songs, field hollers, and so on.

Then, around 1940, folk entered the realm of popular music when a quartet from New York called the Weavers started playing a regular gig at the Village Vanguard in downtown Manhattan. The Weavers became so wildly popular, well beyond New York, that not even McCarthyism could extinguish them from the popular consciousness. You can blacklist a performer from the radio, but you can’t blacklist a melody from the minds of millions.

The Weavers’ intentional approach to the form—dressing in their Sunday best and singing perfectly polished, digestible versions of traditional songs they learned from filthy folkies like Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly—meant that they set out to make folk music popular. They wanted the songs to sell very well, for the tradition to become planted in the hearts of countless fans. They wanted whatever was taking place in that cultural moment in America to include the deeply rooted folk music tradition that existed throughout the country before there was such a thing as a record industry. And they succeeded, House Un-American Activities Committee be damned.

The Weavers’ contiguous tenure, from 1940-1952, was remarkable considering they were playing traditional music. A recording of their Christmas Eve 1955 reunion concert at Carnegie Hall became one of the best-selling folk music albums up until that point. By then, folk music had a firm place in the realm of “popular music.” Even as Elvis Presley tore up the charts, there was yet room for Harry Belafonte and the Everly Brothers.

Bob Dylan wouldn’t show up at Newport Folk Festival until 1963, introduced by Joan Baez. Worth noting, Newport has continued to draw folkies for decades, even after Dylan moved on to other things. Two years after he asserted his artistic independence, the film Festival documented Johnny Cash and June Carter, Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, the Staple Singers, Mimi and Richard Farina, Peter, Paul and Mary, Judy Collins, and countless others, proving the staying power of the form regardless of the rock and roll or blues aspirations of its favorite son.

The ’60s saw a boom in folk music on the national scene, as the hootenanny crowds from Washington Square Park in New York became stars on the city’s stages, like the Bottom Line, Gerde’s Folk City, and other West Village haunts. This tight-knit community of singers, songwriters, and folk traditionalists drew inspiration and material from Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, as much as they did from the Weavers. Folk music also became deeply intertwined with the socio-political rollercoaster of the decade, as songwriters grappled with the civil rights movement, America’s involvement in Vietnam, political assassinations, and wide access to new recreational drugs.

Further, communities of folksingers in Woodstock, New York, and California’s Laurel Canyon started to make waves as the decade closed and the next one unfolded.

The 1970s brought a rash of folk-rockers to the realm—the Byrds from the West Coast and the Band from the East. Singer-songwriters like Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Jackson Browne, and others emerged from the Canyon. Simon and Garfunkel parted ways and Paul Simon stepped to the front. These and other singer-songwriters filled in a hole left by Dylan, who was by then toying with country music and born-again gospel.

The dawn of the next decade saw a renewed vibrancy in the New York City-folk scene, with the opening of the Fast Folk Café. As the years marched ahead, a passel of women singer-songwriters leapt from that community onto mainstream labels like A&M, Columbia, and Mercury Records.

Suddenly folkies like Michelle Shocked, Suzanne Vega, Shawn Colvin, and the like were deemed radio-friendly. The phrase “confessional songwriter” came in vogue, to offset the nonsense of pop music at the time. There was radio and dancehall music thinly veiled in its sexual references (a whole lot of men and women wanting to “dance” together in the ‘80s) whereas the folksingers supposedly had something to confess. Those artists who managed to crossover to a wider audience became known as folk-pop, a designation loosely tied to anyone with an acoustic guitar in the band, regardless of whether they had an allegiance to a specific musical tradition or not.

Confessional songwriting was the new cliché about folk music that offset not only new wave ‘80s pop but also, as the decade turned into the ‘90s, a rise in punk energy via grunge and hip-hop. Folk in that decade became synonymous with quiet introspection. Even as mainstream record producers added their magic touches to flesh out songs by Patty Griffin, Paula Cole, and Sheryl Crow for the charts, the artists continued to make music from their folk roots. Communities formed, new festivals popped up, and the folkies started traveling in packs. The late-1990s “girl power” tour Lilith Fair connected innumerable singer-songwriters and erected a side stage for the debut of up-and-comers like an adolescent Brandi Carlile and old favorites with new solo careers, like Susanna Hoffs.

There was nothing comparable for the men, aside from the sizable space they took up in the rest of the music industry. But the lessons of Lilith Fair—especially the power possible in collaboration—were nonetheless learned by industry insiders as well as artists who hoped to gain a significant audience.

Coffee shops became the new place to hang out and their proprietors started booking singer-songwriters to provide both entertainment and background music. Soon there were two waves of coffee shop folkies. There were those who were hired to mostly play cover songs, with a tip jar out in case anyone wanted to throw a dollar in. Then there were those who were prolific, compulsive songwriters, who peppered their sets with the occasional cover but held court on the stage to discourage you from reading or studying or engaging in conversation. Sometimes, the performer was so good at drawing crowds to the coffee shop, they could graduate to the local bar and maybe, eventually, a theater.

As the century turned, solo singer-songwriters poured out of the coffee shops, but there was also a certain bluegrass flavor to so much of the rising folk scene. Debuting in 2001, the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? was so popular on the star-power of dreamy George Clooney lip-synching to bluegrass standards, that an enormous amount of soundtrack units sold on its heels. This plucked Welch and Rawlings from near-obscurity to folk-fame. Alison Krauss & Union Station took center stage as well, and audiences became accustomed to hearing throwback lyricism and tight, mindful harmonies, broken up by stellar, dexterous instrumental breaks.

Dar Williams, who cut her teeth in Boston’s singer-songwriter scene during the 1990s, met The Milk Carton Kids when they were her opening act on tour just after they released Prologue. She was impressed by their professionalism and their self-possessed way of interacting with her rather loyal audience. “They knew right away,” she says, “that this was about respecting themselves, and also loving the audience.”

Further, Williams notes, when O Brother came out: “Suddenly we discovered that we wanted a certain kind of folk music that had those hints of Depression-era instruments and ensembles—even themes. … [Artists at the time] made beautiful music but there was more musical virtuosity than lyrical originality. That’s where the needle shifted to.

“What was interesting about The Milk Carton Kids,” she adds, “is that they wrote these great songs and they kind of looked like these up-and-comers. … Then you realized their harmonies had the beauty of this new Americana sound. And then Kenneth would pull out some wicked guitar solo and you’d realize that the musical virtuosity was there too. I think it’s a testament to who they are that I recognized them as fellow songwriters first, and then I realized they had the chops of that new Americana look and sound. They brought those two worlds together.”

True, in the handful of years preceding Prologue, folk music was now running wild in these and other numerous directions. There were the bluegrassers but there were also large bands, often upwards of seven members, playing quiet, precious music. The phrase “orchestral folk” was being thrown around for bands like Lost in the Trees or the Sparrow Quartet. Some of these groups had studied jazz and classical music and now brought their violas, cellos, and bass mandolins in front of folk audiences.

There were smaller bands with a four- or five-member rock and roll style lineup. These artists grew up listening to grunge and acted out their rock and roll fantasies on folk instruments. This new era of folk-rock splashed particularly large when Mumford and Sons broke with a young scene of UK folk hopefuls close behind. From the south came the Avett Brothers with their jumping and twirling, their wandering cellist. From the opposite direction, the Pacific Northwest, came bands like the Fleet Foxes and Blind Pilot, with their gritty chorales of backup singers, the occasional ukulele or whistling solo.

So it was some strange sort of kismet when a couple of solo singer-songwriters named Joey Ryan and Kenneth Pattengale crossed paths at Los Angeles’s Hotel Cafe at the end of 2009. Both were making their way through the singer-songwriter world, alongside the grunge folkies, the orchestral folkies, the folk-rock newcomers, the bluegrassers, and the standard stand-alone singer-songwriters. Both were recording their solo efforts and selling them bootleg-style at their club gigs.

TWO BECOME ONE

Listening to Pattengale and Ryan’s solo work now is something of a revelation, though all of us music journalists did it when we first heard Prologue a decade ago. At the time it seemed like two talented, as-yet obscure singer-songwriters just decided to join forces and make a go of it together. And, granted, that is true. But listening back now, we can hear the emotional urgency of a couple of young men who have certainly found their voices but also wield the uncertainty of what, exactly, they are to do with them.

(“It’s like a Beatles thing, where the whole is greater than the parts,” says Cash. “Although the parts are pretty great too.”)

The pair met in December and were rehearsing together two months later. By March, remembers Pattengale, “I’m ‘sitting in’ on the third of Joey’s four-week residency at Hotel Cafe, celebrating the release of Kenter Canyon. By March 30, we had already done a photoshoot together, booked a Kenneth Pattengale & Joey Ryan gig at McCabe’s, and vowed to join each other on everything going forward.”

Kenter Canyon was Ryan’s 2010 solo EP, featuring backup from Rawlings and Sara Bareilles and released a few weeks after he met his new collaborator. Aside from glowing reviews of that EP, there are other traces of their two separate careers to be found on the internet: Pattengale’s polished music video on the one hand and some live clips with his alt-country band—rock and roll lineup, plus fiddle and pedal steel—on the other. There, he strums chunky chords and sings like the second coming of Jeff Tweedy.

Listening to the early recordings of these two men together, before they settled on a band name, we can hear the way their collaboration unleashed the most relaxed, evocative, intensely emotive music that was perhaps on offer in the U.S. at the time. (Rose Cousins was doing something similar in Canada and Laura Marling in the UK, though both were solo artists.)

The Milk Carton Kids worked out some of the same songs from their solo careers, but with a quiet confidence that the music they had created together might be sufficient, may not need any additional filigree. Against the emotionalism of their individual songs, the pair fell into place with Ryan’s Gibson holding down the foundation and Pattengale’s Martin dancing atop. Harmonies were defiantly close. Folk and country legend Emmylou Harris recognizes that what Ryan and Pattengale were able to accomplish with their harmonies is something toward which all singers reach: “How two voices together create a third voice.”

Gone was the urgency, replaced instead by, you might say, something a little more permanent.

“I don’t recall ever working on the singing,” says Pattengale. “We worked a lot on choosing the notes we sang, but never discussed how our voices would fit together. They just did.”

The music was quiet. It forced a loud crowd to pull together, come closer, pay attention. Folk music has always, by virtue of its shape and size, physically brought people together. Consider the way people naturally joined arms in response to “We Shall Overcome.” Recall photos of performers during the early days at Newport in front of a crowd of full-grown adults who sit almost shoulder-to-shoulder, legs crossed in the grass. Folkies who don’t play into the physical connection that comes from making quiet, contemplative music, are missing at least part of the point.

The Milk Carton Kids have never missed the point.

Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Sarah Jarosz, who has performed with the duo several times, recalls that working with them “was the first time I had been around other musicians who were not only focused on the music part but aware of the other parts. Not only the sound aspect but the physical aspect. They’re entertainers in that way. They’ve always been conscious of creating a complete experience for audiences. … The intimacy that they’re able to [create] sucks the air out of the room, in the best way. It really makes you lean in.”

Appearing first as an all-but-unnamed duo, Pattengale and Ryan tried on the clothes of supportive singer-songwriter pals. Soon, it was clear that a band was forming. Their names alone were not compelling enough to make people take notice, so they landed on “The Milk Carton Kids,” after a song they’d written, and booked a calendar of dates.

They also started performing in suit and tie—a decision that was, in the vein of what Jarosz recalls, part of their mindful attempt to create intimacy with the audience. Plus, notes Ryan, “I love putting on a suit every night to perform. It makes the show feel sacred, like a wedding or a funeral.

“But we really needed the suits early on, in the dive bars and coffee shops. When the floors were sticky and everyone was just there to hang out, taking the stage in formal attire helped us quiet the room and turn everyone’s heads, just for a minute, so our quiet little show stood a fighting chance. We probably didn’t realize we looked like Greenwich village folk revivalists, but I do remember not wanting to wear suspenders and pork pie hats. That would have felt too much like a costume for a couple L.A. kids.”

Indeed, what set The Milk Carton Kids apart from their new folk peers, aside from the sheer size of their band (or lack thereof) was that they were playing music that just was what it was. Like the photo of a missing child, its emotional punch was what you could take at face value. Suits and ties aside, there was no dressing up the actual music. What it appeared to be was what gave it impact.

Besides, says Cash, “Kenneth’s guitar playing just blows me away. He’s channeling some really deep, sophisticated stuff. That vocal blend is almost as tight as brothers. … Their intuition as singers is as close as brothers but still with the edge of people who aren’t related by blood.”

True, there’s a certain magic when siblings sing together. Some combination of genetics and the memory of a childhood spent in the same brand of chaos, the same soup of emotion and boundaries.

In the same way eating is mostly about smell, so is singing mostly about listening.

Hearing each other’s voice every day for a lifetime, allows siblings to get musically close to one another without becoming uncomfortable. Sibling voices, combined, shed a light that’s near impossible to turn on when collaborators come from different homes or parts of the country. There is much to surmount in getting to know another individual, so there is something lost in the coming together of two people, always. A divine tension.

While no amount of touring in a van or crashing on each other’s couch can supplement for all the knowledge siblings have about one another’s voice, there is something almost incongruous about what we were treated to when Joey Ryan and Kenneth Pattengale came on the scene. They backed each other up for only a year and a half before they released Prologue and yet, in that short time, they’d crossed the threshold to sound like a pair of brothers exercising their family’s pain through music.

The duo’s harmonies have been celebrated by big-shot record producers, Grammy voters, poets, and elders in their field. And though I just spent a few paragraphs likening the way their voices blend to something familial, it’s worth taking time to revel in it more specifically.

Listen to the space between the notes on “Stealing Romance,” for example. The way they start and stop each lyric. The careful trailing off, like lifting a pipette when squeezing out meringue—that soft fluff of whipped egg that points into the air before draping over itself.

Neither singer hits it harder than the other. The s’s and c’s and t’s—consonants that careen toward chaos in lesser collaborators—land at precisely the same instant. There are tricks for doing this in harmony, but if you crank up Prologue and don headphones, you can hear two distinct voices at both the beginning and end of every word. And while this is perhaps a technicality, too far in the weeds of singing geekery for the average listener to know or care what I’m getting at here, it is still worth celebrating the fact that Pattengale and Ryan have a magical synergy unlike almost any other band in the history of folk music, whose members didn’t grow up in the same house.

That they are a decade on and still consistently deliver on their particular blend of great songwriting, near-sibling harmonies, and musical virtuosity, makes one wonder what kind of magical golden thread was fashioned, and from where, to hold together these two unrelated musical souls.

EPILOGUE TO PROLOGUE

Prologue, when it was released, made a certain impression that carried their audience along to The Ash & Clay, where the duo stretched its legs and settled into its collective Self. Similarly, each consecutive The Milk Carton Kids release has carried the listener slightly further on a certain path. But it’s worthwhile to gaze back now and then, to recognize the sort of artistic prophecy that existed at the very beginning.

After all, the aptly named Prologue delivered some foreshadowing hints for us. Whether Ryan and Pattengale had a feeling about how their career would pan out—via songs like “Memphis” or “Unwinnable War” or “The Only Ones”—is unlikely. But, on “Milk Carton Kid,” the title track for their band, they drop what has proven to be somewhat of a thesis statement for their partnership.

I don’t feel the pain I once did one day it just vanished like a milk carton kid.

True, with hindsight, we can say for sure that, for all the heartbreaking exactness, the quiet devastation at the heart of their lyricism, there is always that backward glance at the deepness of pain. There is always the revelation that we get one present moment, and then there is the way the present moment immediately drifts into the rearview to make space for the next present moment. And on and on until real pain is just an echo of the pain one once felt.

Consider Prologue’s opening track “Michigan.”

All that’s left is a blind reflection / You know what’s coming and you regret it

There is pain in the leaving behind. There is perspective in being able to look back on pain, to glance in both directions at once. And when the singers divulge their view from down the road, we can all feel it together and begin to heal. Especially when the song culminates with the half-cliché:

You took the words right out of my mouth / when you knew that I would need ‘em.

It’s clear Ryan wasn’t the first person to coin the delightful imagery of removing words from a person’s mouth. But what makes the cliché bearable instead of inciting a pop-like eyeroll is the way he finishes the sentence.

Consider that “you took the words right out of my mouth” is often an admission that two people are so connected, they can finish each other’s sentences. But what, then, when the love goes wrong? Packed into this brief pair of lines is the implication that this deep connection has soured to the point where finishing a lover’s sentence is akin to theft.

Further down the track list comes “New York,” a song the duo sat down and wrote together, line for line. The song’s sincerity is matched by its sarcasm, wrapped up in a ribbon of that O Brother bluegrass-folkiness. They completed it with Pattengale’s dexterous guitar work, despite the very un-bluegrassy destination of the song’s protagonist.

You said it just right / I never stay / long enough to fight / I just run away.

This opening line comes close to admitting our protagonist is an overgrown child incapable of legitimate love—an irony canceled by the fact that an actual child would not deign to admit this in the first place. Then the singers drop the somewhat joke, arguing that there is good reason for this avoidant coping mechanism. To boot, it is all wrapped in a sentimental harmony so sweet you can miss the jab of the lyrics if you let your ears blur for a half-second. But zoom in and you can hear it clear.

Its you, my love / It’s you I’m running from.

You would never say this to someone’s face, so to sing it against such a beautiful melody is so painful, it’s downright funny.

The line is an echo of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” a song so superior in its sarcasm toward an ex-lover that one almost wonders why any budding songwriter would try to redo it. But the way influence works is more insidious than explicit.

Listen to a song enough times and the ideas, language, and inflection becomes part of the way you think. Occasionally a songwriter might want to do something the way their influences did, but aping a hero mindfully never pays off. Whereas, if you’re careful with the writing, the influence inadvertently comes out anyway, on your voice, wearing your own clothes.

In this way, The Milk Carton Kids don’t exactly one-up the masterful folk bard, but, on their inaugural album—with no track record for fans or critics to fact-check, mind you—they nonetheless do the theme significant justice.

I’ll be in New York / Send for me if you want more / I’ll be in New York / Without you / like before.

The nods to folk legends don’t stop with this one.

“No Hammer to Hold” tips its hat to the traditional bluegrass standard “Nine Pound Hammer,” itself a nod to the legend of John Henry, who allegedly died with his hammer in his hand. “I Still Want a Little More” could just as well have come straight from that other duo of singing siblings, the Stanley Brothers. “There By Your Side” is vintage “Sound of Silence”-era Simon and Garfunkel, even packing a slight Garfunkelian tinge on Pattengale’s lead vocals.

“You go along, and you think you’re never going to hear anything that’s interesting. Everything been done,” says Nashville legend Emmylou Harris, herself a fan. “But let’s face it. We all draw from the past and people who have come before. We all do that. But what you have to do is absorb all the stuff that moves you and then come up with something different, and that’s what they’ve managed to do.”

Indeed, the duo’s backward gaze to all that came before is their indelible link to the mindful evolution of American folk music, with all its twists and turns, its unexpected-yet-always-timely reformations. Where, as Harris said, many artists start from their influences and grow into their own unique amalgamation, The Milk Carton Kids took the time on Prologue to assert that this duo would amount to more than simply the happenstance of a pair of navel-gazing songwriters who stumbled into each other’s lives and popped out a handful of records.

THIS AIN’T NO TIME FOR REGRET

The same summer Prologue dropped, Bonnaroo—the Tennessee music festival typically teeming with the most popular rock bands on the scene—was loaded with folkies. Mumford & Sons and the Decemberists were toward the top of the bill. Old Crow Medicine Show was there as was The Head and the Heart, Justin Townes Earle, Abigail Washburn, Alison Krauss & Union Station, Hayes Carll, and Ben Sollee. Then there were the more tertiary folk-rock bands like Deer Tick, My Morning Jacket, Iron & Wine, the Low Anthem—all tugging on the roots of roots music. These were the dominant purveyors of the form at the time, and this was the sonic landscape into which The Milk Carton Kids wandered. It’s stunning, really, that they managed to break through the din with their free-download album.

Nonetheless. Through the banjo-shredding, hair-wagging, singer-songwriter-centric, Arcade Fire-obsessed musical landscape of 2011, strolled this quiet pair of folkies in suits, to make their mark. It was a dizzying musical moment for anyone paying close attention, but The Milk Carton Kids have always been focused on a bigger picture.

Their music is not just about the emotional economics of any given moment so much as it is about what this kind of music can be, what it can do. How the act of two voices telling the honest truth can lift an audience out of chaos and land them in a soft spot. The one thing folk music has always had going for it is that there is a stability that comes from hearing a pair of voices otherwise unadorned. We all need to hear our feelings reflected back at us in a way that doesn’t hide them under layers of distraction.

So, as anachronous as it may seem with a decade of hindsight, the statement The Milk Carton Kids made with Prologue was perfectly fitting for that musical moment. But time has also proven they were more than just the right band in the right place at the right time. Prologue set the tone for how their audience could expect them to show up from then on. And album after album, they have reliably, consistently delivered on their original promise: When there is so much noise and motion, it is the quiet and calm that prevail.

THE MILK CARTON KIDS’ PROLOGUE 10TH ANNIVERSARY BOX SET IS OUT NOW.