By the time Neal Francis wrapped up his second album In Pain Sight in 2021 and embarked on a tour spanning 400 shows through 2024, the Chicago-based singer-songwriter and pianist had already started working on what would become his third release, Return to Zero.

Drawing from songs he wrote during the pandemic quarantine and demos recorded with longtime collaborator Sergio Rios, and others written while he was on the road, Return to Zero was in the making for years. “It [the album] feels old to me now,” Francis tells American Songwriter. “It’s been kicking around for a while.”

Co-produced by Rios, who has worked with Francis since his 2019 debut Changes, Return to Zero fetches lusher pulsating arrangements around disco and rock and roll, from the opening discotheque grooves of “Need You Again,” “Don’t Wait”—the latter with some life advice—Don’t wait to live your life / It’s gone before you know it and you might not get it twice / Don’t wait / To live your life / Turn on all the lights / See that you look fine—through “Broken Glass,” all featuring Brooklyn-based “discodelic-soul” trio Say She She on backing vocals.

“Broken Glass” came out of a jam session with Queens of the Stone Age bassist Michael Shuman on drums, while Francis played bass. “It was the first time we met, and not only did we have fun, but left with a complete song,” said Francis in a previous statement. “The lyrics were free-form material I had written down about sub/dom relationships in the bedroom.”

Disco, soul, and funk fuel most of Return to Zero with “Dance Through Life” and “Dirty Little Secret.” Midway in, dreamier classic rock riffs and Xanadu vibes fit the anthemic pop of “What’s Left Of Me,” which Francis co-wrote with Chris Gelbuda (Zac Brown Band, Sabrina Carpenter), with some more piano twists on “150 More Times.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Another touch of rock hits with “Already Gone” and the more soulful “Can’t Get Enough” before everything closes on the electro-chimed instrumental “Return to Zero,” a piece Francis originally wrote as the outro for another track.

En route to his New York City show, Francis spoke to American Songwriter about melding rock and disco for Return to Zero, developing the next round of music, and the crazy idea of making a Johann Sebastian Bach opera that has nothing to do with the classical German composer.

AS: Since you spent years with some of these songs, were there any tracks that have shifted the most as they were fleshed out, and by the time you go into the studio?

NF: Some of them did. Some of them remained unfinished. I think it’s a bad practice for me to spend that long holding on to songs, because I have too much time to think about them, and then I start to question everything. And by the time I’m recording them in the studio with the band and mixing them, I’m like, “These songs are bad.” It’s just my own neurosis, but it also encourages me to form a new discipline around my creative process.

[RELATED: Neal Francis ‘In Plain Sight’ Interview]

AS: Was it always like that for you, when it comes to writing, and holding on to songs too long? Are you still the same songwriter you were when Changes came out?

NF: I think what changes is my interests and my goals as far as the aesthetics I’m pulling from. I’d like to think I’m getting better at songwriting, but I think that’s hard to quantify, too. I think what improves in me—and I sound like a mundane person—but it’s my discipline, my ability to knuckle down and get things done.

AS: Taking all of this into account and the time spent with these songs, how did you feel once Return to Zero was finally complete?

NF: I stopped listening to it entirely, and only now, after it’s out, am I able to appreciate the recordings. I appreciate the work everybody did. I’m grateful that I had the ability to take a step back far enough to appreciate that everything was at a certain technical standard for me. I had people around me helping, but I learned during the last process with In Plain Sight that I had to sort of take some space from it. You live inside the record for so long that it just becomes nauseating, as anything would with that level of closeness.

I don’t think anybody has spent more time with it than me, so I took a nice break, and then when we started rehearsals, there wasn’t a lot of listening to the record, even in that process. We rehearsed probably 25 times before the tour, and the songs came together in their own way, because it’s this ensemble. It’s a four-piece playing songs with these arrangements, so it takes on a form of its own in the live setting, which is always how I’ve operated.

AS: You’ve been working with (co-producer) Sergio Rios for years now, since Changes. What is it that continues to click between the two of you?

NF: Well, Sergio and I have a very common musical lexicon—not just specific bands, but overall aesthetic. I met him because I was a fan of his band Orgōne, and I liked the way their recordings sounded. He recorded the band that I had prior to Neal Francis, called the Heard, with our bass player, Mike Starr, and I got a glimpse into his process and started learning about the analog workflow. It’s just fun spending time with him at this point, because we’re such good friends, sometimes more like siblings. I’m really close to Sergio, and I’m sure we’ll work on more stuff. I also like having worked with him so extensively. I’ve also begun my own journey with engineering and producing, and I hope to do much more of that.

AS: You mentioned wanting to experiment with a concept album at some point. Was there anything that came out of the album that you want to change the next time around?

NF: I would love to make a concept record and our new guitarist, Austin [Koenigstein] and I’ve been joking back and forth with different ideas, and my friend Dom [Dominic Frigo] is piggybacking off of this joke of making a Bach rock opera that’s about the life of [German composer Johann Sebastian] Bach. It’s a rock opera that doesn’t reference his music or his aesthetic at all. It’s just this totally obtuse thing.

Over the last few years, I’ve been cultivating a lot of equipment. I have a great space in Chicago that used to be a storefront with 13-foot ceilings and a large enough space that I have everything set up so we can really control the means of production ourselves.

AS: For Return to Zero, how did the songs end up tying together in the end?

NF: It happened afterward. There was this one point where Elliot Bergman was producing the record for all intents and purposes, and he was integral in the pre-production process. He sat me down one day and said, “It feels like we’ve got two halves of two records. You’ve got a disco record you’re working on and a rock record you’re working on.” And there just wasn’t enough time to fully realize that, or maybe I didn’t have the energy or the bandwidth.

That was my struggle for this record: having enough gas in the tank. The sequence was supposed to be even more like “side A, disco, side B, rock,” but we just Frankenstein-ed the rock disco record together. There was also a compromise with [label] ATO. They really wanted “What’s Left of Me” to appear on side A, which was not my concept at all. … So coherence-wise, that’s kind of why it still feels like it’s very incoherent to me.

AS: “What’s Left of Me” is definitely where that shift happens from disco to rock.

NF: It [closing “Return to Zero”] was supposed to be the outro for “What’s Left of Me.” That was supposed to be a suite. If only everybody would just listen to me.

I’m kidding. I was happy to compromise.

I’m gonna take two seconds here just to say that I don’t want to sacrifice the importance of sequencing, because I think this whole era of streaming and short attention spans is full of crap. As an artist, my protest is making things the way I want to make them, and doing things on stage the way I want to do them, and not kowtowing to some algorithm.

Streaming is still wonderful. It’s changed the way we listen to music a lot. I found our guitarist Austin, on Spotify and his band, Smushie.

AS: Why did you land on the title Return to Zero?

NF: The title was this moment of grace that was beamed down to me, and then it was the thing that synthesized everything.

AS: Sonically, is there any direction you’d like to explore?

NF: I’m working a lot more with synthesizers and sequencers, and drum machines. And I made this disco record without drum loops, which was so stupid, because that’s what all our favorite disco tracks did back in the day. I’m interested in learning by doing, which is something that comes from an architecture background.

I want to start with learning what the process was like in the ‘70s, making a tape loop and then recording it that way.

AS: Have you already moved on to the next thing?

NF: Yes. I have a notes file that’s growing, and I have voice memos and a file that’s growing, and I have a playlist on Spotify with all these cues. The working title is Project 2025, because I want to f–k them. I’m sorry, not to get political, but I want to feel free to explore, so I’m excited about the new stuff I’m creating.

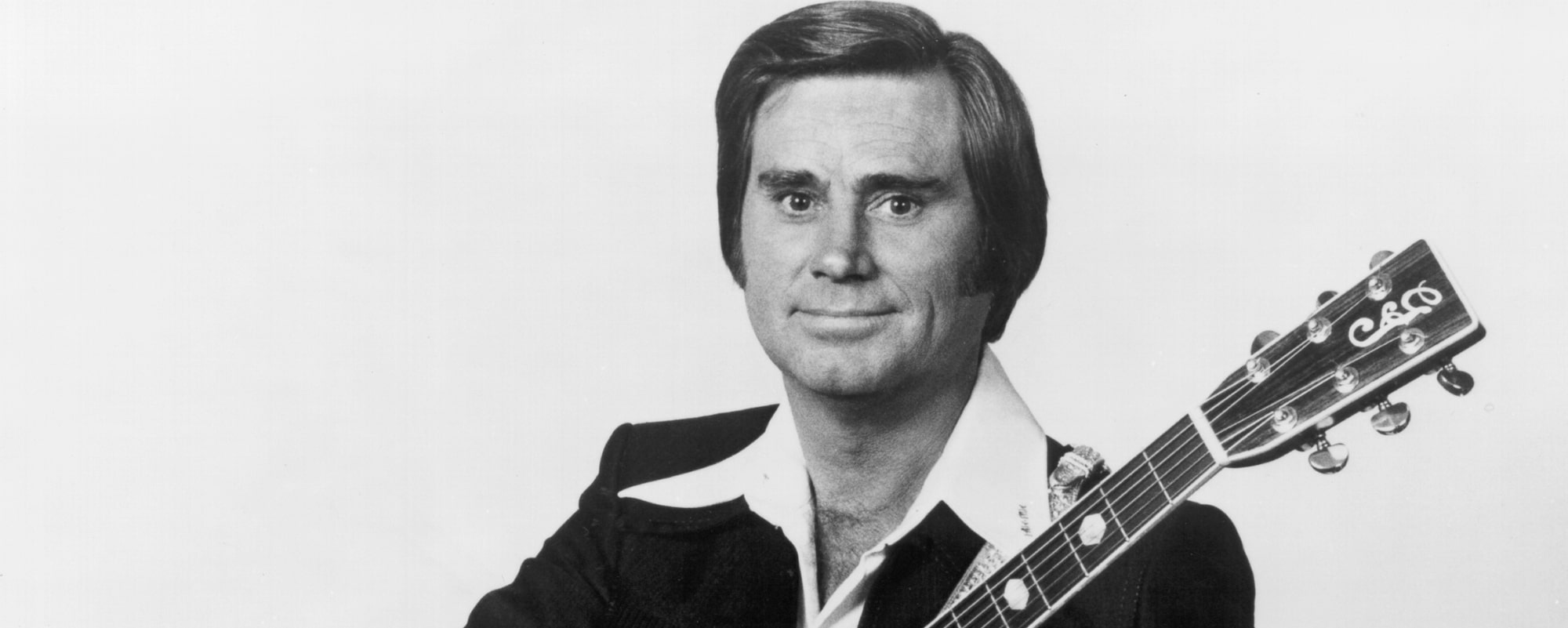

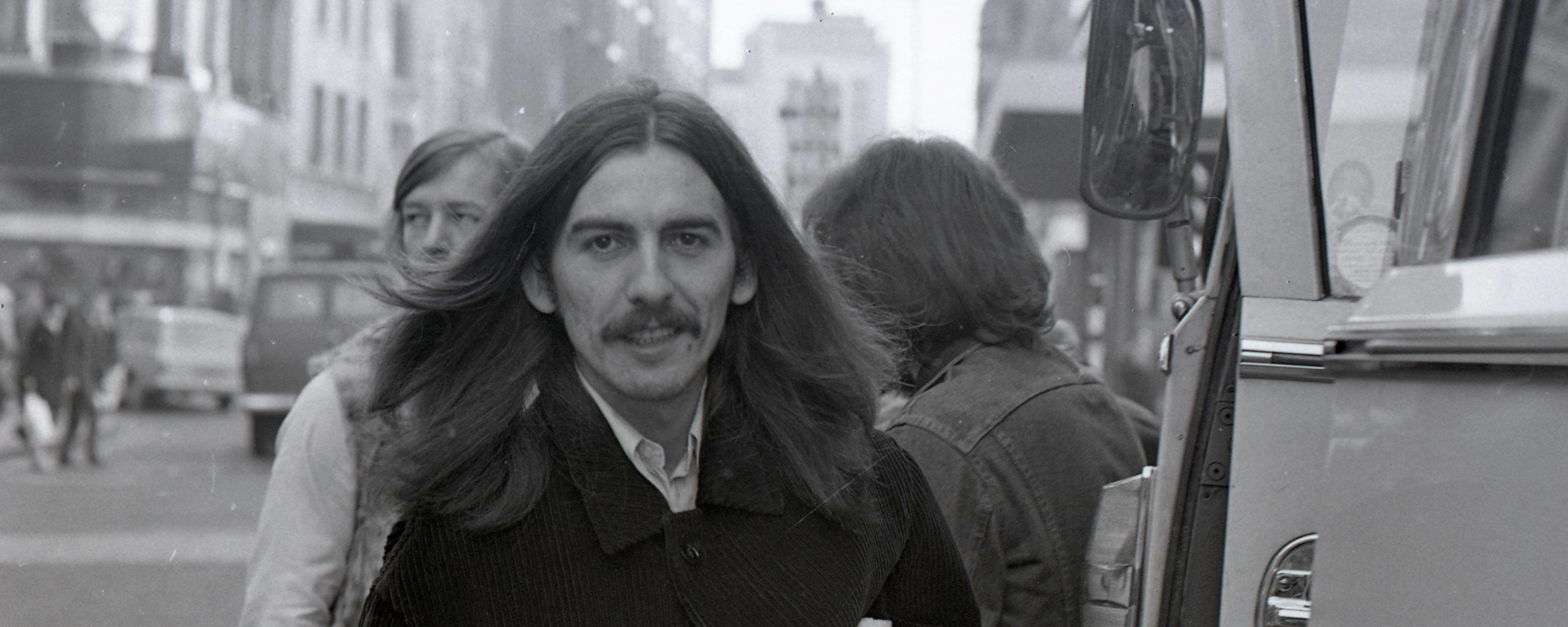

Photos by Jack Karnatz

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.