These last weeks have been surreal for the usual awful reasons now: pandemic, lockdown, cancelled gigs, riots, earthquakes, fires raging in our cities and over millions of acres of forest here in California. Every night the once golden sunset was orange as a Halloween pumpkin.

Videos by American Songwriter

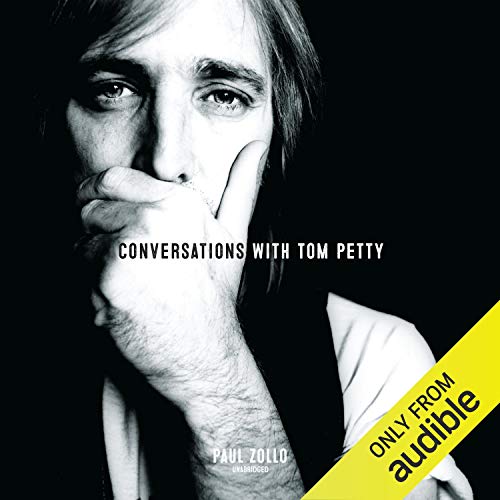

It was in this strange surreal season that I first heard the audiobook version of Conversations with Tom Petty, The Expanded Edition. I’ve written other books, but this is the first one that Audible made into a talking book.

This is a new edition published this year, with much added material, of the original book that Tom and I did back in 2005. It is a collection of conversations with him about his songwriting mostly, and being a songwriter, but also about his singular history.

Doing the audiobook seemed like a good idea, but a challenging choice, as there is not one voice but two. There’s Tom and Paul. We both wrote separate introductions for the first edition, and the rest of the book are the conversations. Q & A.

So did that mean they would get two actors to read the two voices?

No. One actor, Jim Meskimen, would do all the voices. He has narrated many books, as well as being a comedian, impressionist and actor. He’s also the son of the actress Marion Ross.

I wasn’t convinced, however, it would work. But it does.

Here’s what I learned being an author hearing my book read like this.

Hearing our book read to me, as opposed to reading it myself, was both great and awful. Great because I realized when a compelling narrative it is, thanks to the power of Tom’s great story-telling skills, and his remarkable life.

Hearing it like this had that fun, easy comfort of being told a story. I’d listen while taking a walk, or driving somewhere. I found that, due both to the content of Tom’s stories, and his great skill as a storyteller, I didn’t want to stop listening. I wanted to know what was next.

Several times while listening as “Tom” told a story, I forgot it wasn’t him. Not because Jim’s imitation is perfect. It isn’t, nor is it intended to be. It’s meant to give you that feeling of Tom’s gentle, humorous spirit, which it does well. He uses a slower cadence and a slight inflection of that gentle Southern accent.

While working on the book, I was careful, as always, to use his exact wording as spoken. The way he told stories – the humor, the arc of emotion and memory – was powerful. He was not only a great story-teller, he was brilliant at condensing a story, as he did in songs, to give us all the elements with no wasted words. It occurred to me that people would hear this and presume we did a lot of editing of his words. But we didn’t. That is exactly how he spoke, and so his spirit is very much alive in the cadence and structure of his stories.

As there was much laughter throughout, I denoted that in the book so that the reader would know it was being said with humor. His laughter always commented on the story; sometimes he’d laugh at how ironic, or stupid, or pointless something was.

Quite often he’d be laughing at himself, or his fellow musicians, such as the time he got a new Corvette, and drove it over to a Wilburys recording session. He showed it off to the guys, and opened even the hood to look at the brand-new engine. Then, with a laugh, he says how not one of them – “musicians, you know” – could figure out how to close the hood.

Or when he said The Heartbreakers were “human to a fault. Just a bunch of lugheads, actually.”

Without the lilt of laughter in the delivery, it would come across that he was more serious than he was. It’s really the only thing included in text that comes across as stage directions. Jim Meskimen did the delivery of these laugh lines well, each measured a little different.

I was also surprised, although I wrote the book, at the breadth of what we covered, and the generous depth with which Tom was willing to dive into these old songs and memories.

Also it is striking, upon listening, to be reminded of Tom’s laser-focus priorities as we journeyed through his past. It was always about music. It wasn’t music for the sake of getting girls. The girls were not attached to what mattered. All though high school and beyond, though he had his romances, never did he get caught up in romantic trauma that would distract him from the mission. As he says, the only time he went to prom was to be the band onstage. Even then, in his season of crazy pinball hormones, it was the music that mattered. The song, the instrument, the rehearsal, recording, gig.

The oddest part to hear for me was the way Mesikimen did my voice asking questions. He brought a lot of character to Tom, which makes sense. But when it came to my questions, he’d read them flatly, almost without emotion. So that although I might be asking a personal question, it would be posed with no inflection at all, like a soft-spoken, calm psychiatrist. Asking pointed questions but with much care, so as not to upset the patient. So that a fairly personal question, such as “Why was your dad hitting ditches so often. Was he drinking?” is spoken in a monotone. To me it evoked the calm voice of Hal in 2001, and felt like a carefully controlled interrogation.

That approach was not unwise, as the book is about Tom, and his character. It is the answers which matter most, and framing it against the stolid tone of the questioner makes Tom’s character seem more vivid and real.

Had I spoken like that, in reality, this would not have turned out well. It would feel like I was trying to mask my actual feelings, which I wasn’t. He was telling these stories, and I was the audience. We sat really close and he shared so much. It was always received with real emotion. Tom wasn’t phony in any way, and if I was, he wouldn’t have done it. He knew my reverence for his songwriting, and my love of learning every song inside out to talk deeply about them, and my laughter at his humor, was genuine. Without that, he wouldn’t have shared so much.

The real sound was like two friends, both musicians, loving to talk about all aspects of music.

But these impressions I had while listening were starker at first. After awhile, I grew used to it. And was genuinely moved by how real Tom’s character is, and what a kind, funny and deep guy he was. Even in his saddest stories, he’d often have some laughs. Such as his off-handed way of explaining how he realized how far gone his dad was. “He drove into ditches so many times,” he said, “I just thought everybody’s father drove into ditches all the time.”

The toughest part of hearing the book read was in the sections that I wrote separate from our conversations, such as the introduction, and several chapters that I wrote completely in this expanded edition. These sections have one voice only, that of the writer. I can’t think of the last time anyone read my writing out loud like that. When someone does, as you writers know, suddenly any weaknesses in the writing came across with painful bluntness.

It could be a little brutal. Some of the language I used,

inspired as it was by his music and spirit, were what my father would call “purple

prose.” By which he meant overwrought, poetic, hyperbolic sentences. On the page,

these work in a whole other way. But when read aloud, any clunkiness in the language

came across like a smoke-alarm.

There were also many sections that cried out for more editing. It was admittedly

an emotional experience to return to this book after Tom was gone, and I did my

best to express the impact of his music in my life and the lives of millions. I

was more worried about understating that impact – which is truly miraculous in

its timeless span – than going overboard.

The publisher was careful about the use of his lyrics in the book. Many times I quoted directly his lines, but they insisted on rephrasing these so as not to quote the song. I didn’t like these either in print or in this form, as it wrecks the beauty of this line we all know. So anytime you hear or any of those – referring to lyrics without quoting directly – that was not my choice.

Parts of his personality came across more powerfully in this setting, read from beginning to end. It showed more than I realized how much he cared about other people, especially Heartbreakers, and also his fans. I already knew this, of course, but it came across with more clarity. Several times he did things for himself which were necessary in order for him to expand artistically and not stagnate. Such as doing “Don’t Come Around Here No More,” with Dave Stewart, and then Full Moon Fever with Jeff Lynne, a solo album. Though he never abandoned his band, these experiences were tough for him, though understated in the book.

One indication of this was when he discussed the difference between working with The Wilburys, which was a fun, friendly and inspiring experience. He said working with The Heartbreakers was never like that. They would create great music, but personalities clashed often.

Another instance which came across strongly was when working on Into The Great Wide Open, which was a band album, but one he made with Jeff Lynne producing. Jeff’s techniques were different than what they were used to, and they gave him grief about it. Yet now, especially, it shows that Tom was trying to take care of everyone. He loved working with Jeff – he said he was the greatest producer he ever worked with, and an exceptional musician – and wanted to continue their collaboration. Jeff not only produced, he co-wrote almost all the songs. Tom knew it was too good to stop, not as long as Jeff was in town, and not back home in London. Good that he did, as “Learning To Fly,” and other great songs, were born.

But the band was really unhappy doing this, which bothered Tom a lot. That he would bring it up for the book showed that it stuck with him for years. He had real empathy, which isn’t an easy thing when being a rock star and bandleader. He walked that line.

But all in all, it was much better as an audio-book than I expected. Jim Meskimen did a good job, and Tom’s spirit shines throughout with his big, gentle heart and a lot of laughter.