Videos by American Songwriter

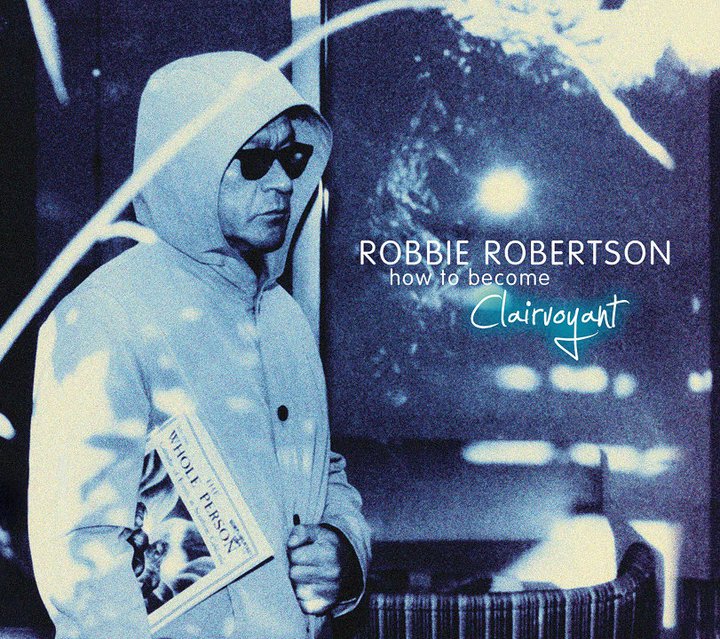

Robbie Robertson

How to Become Clairvoyant

(429)

[Rating: 4 stars]

It’s worth mentioning that the 13 years separating this new Robbie Robertson effort from his previous one in 1998, is five years longer than the original lineup of the Band was even together. The guitarist/songwriter wasn’t on a total sabbatical during that time; he worked as musical director on some Martin Scorsese films, produced soundtracks for others, was employed by Dreamworks as an A&R executive and appeared sporadically as guest guitarist for other artists. Inspired by encouragement from friend Eric Clapton—who appears on seven tracks here and even sings one—Robertson recruited heavyweights such as Steve Winwood, bassist Pino Palladino and co-producer Marius de Vries to record twelve tracks that wade in soulful atmospheric moods and personal lyrical introspection on this generally inspired comeback.

Those familiar with the songwriter’s previous four solo albums will recognize his grainy, airy, occasionally whispered voice seldom heard on any Band material. His muted, somewhat ragged singing meshes well with lyrics that recall life-altering moments he has not shared with the public previously, at least in song, specifically his decision to leave the Band in “This Is Where I Get Off.”

Mid-disc duets with Clapton on “Fear of Falling” and the haunting ballad “She’s Not Mine” provide a few of the melodic and melodramatic highlights. Clapton’s ghostly instrumental “Madame X” with subtle, barely there “additional textures” from Trent Reznor is one of the guitarist’s most subtle and poignant performances.

Lyrically, Robertson’s listing of his guitar influences in “Axeman” borders on the clichéd platitudes he has typically avoided in the past (the corny “people coming from miles around, just to dig that crazy sound” is a long way from the determined frontman self-doubt of “Stagefright”) but when he latches onto an intriguing concept such as on the spiritually based title track, flashes of greatness are evident. The mid-tempo “Straight Down the Line” features Robert Randolph’s pedal steel lines weaving through the narrative of older blues and gospel musicians who won’t sell out to rock and roll, and borrows the lick from “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” to hammer home the point. As its title implies “When the Night Was Young” harkens back to Robertson’s early days supporting Ronnie Hawkins, with moving references that never descend into maudlin.

The evocative, moody instrumental “Tango for Django” captures the spirit, if not the sound, of the great guitarist as Robertson’s gut string playing hovers over shape-shifting cello, violin and accordion that closes out this reflective set on an appropriately melancholy note.

I’m confused by the first sentence of this article. The Band formed as “The Hawks” in 1960 and split up in 1978. That’s 18 years. How is 13 years 5 years more than 18 years? Their first album as “The Band” was released in 1968. So, even if you were going by that, it still ten years.

Hi Bob, I was figuring the Band’s (with Robertson) eight year recorded career, from Big Pink in 1968 until the Last Waltz in 1975. Not their time as the Hawks or backing Dylan when they weren’t officially named the Band. Hal