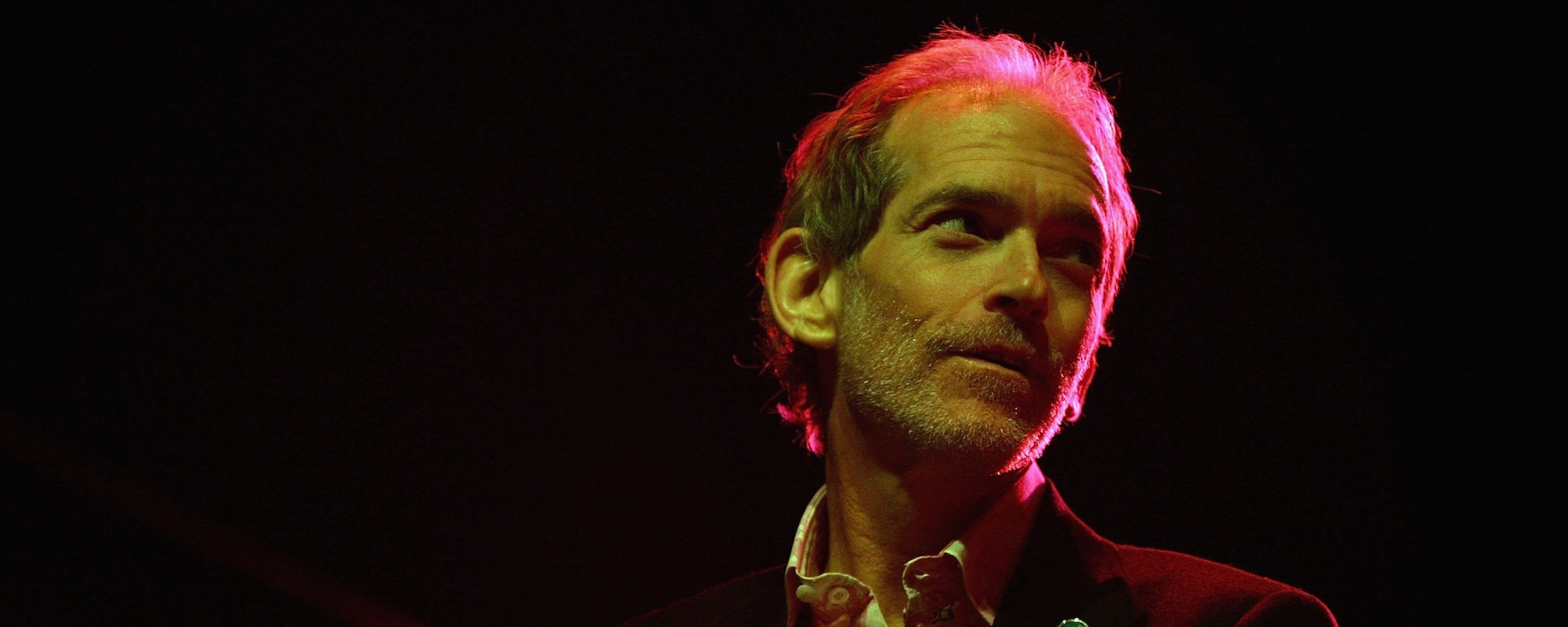

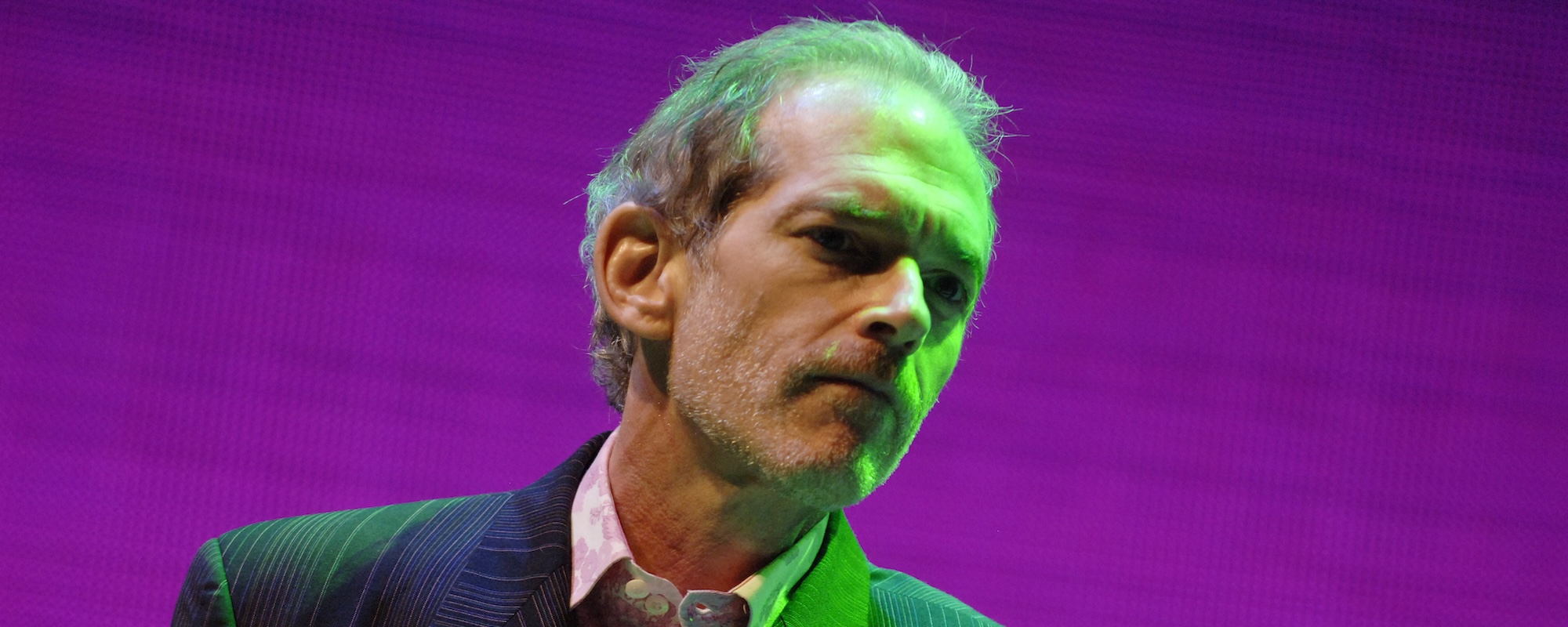

On a trip to Italy with his family during the summer of 2025, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers‘ keyboardist Benmont Tench brought along a few stories he was unfamiliar with, from Mick Herron’s 2010 book Slow Horses, another on Egyptian mythology, and Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which he had never read. Literature, art, and philosophy have always influenced Tench’s performances and songwriting.

“If you read a lot, you hear parables and fables and phrases,” Tench told American Songwriter. “I’m not what you would call a ‘believer’—I’d probably be called a heretic or burned at the stake—but I find a beauty in the Bible and the stories to be an infinite source, as is Shakespeare, and some of that finds its way into songs.”

Tench also referenced Walt Whitman’s 1856 poem, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” a metaphorical piece on how humans are connected through space and time. “That’s the highest form to me, of art, be it drama, comedy, poetry, instrumental music, songwriting, film, visual art, performance art,” said Tench. “If you can reach that far through space and time, even if you’re in the same room, six feet away, into the person, and really deep into the awareness of that person, that’s really something.”

On Tench’s 2025 solo album, The Melancholy Season, his second since his 2014 debut, You Should Be So Lucky, the song “The Drivin’ Man,” centered around a man driving south on the freeway in Los Angeles, was influenced by the works of Raymond Chandler and Joan Didion.

Videos by American Songwriter

“It wasn’t deliberate, but Joan Didion so famously wrote in ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’ about doing the circle of the LA roads and freeways,” said Tench. “And Raymond Chandler, in his novel ‘The Little Sister,’ has an entire chapter where he drives from Hollywood before freeways were there, across the valley, over the hills, down to Malibu, and down the Pacific Coast Highway and back home to where the character’s house was in Hollywood.”

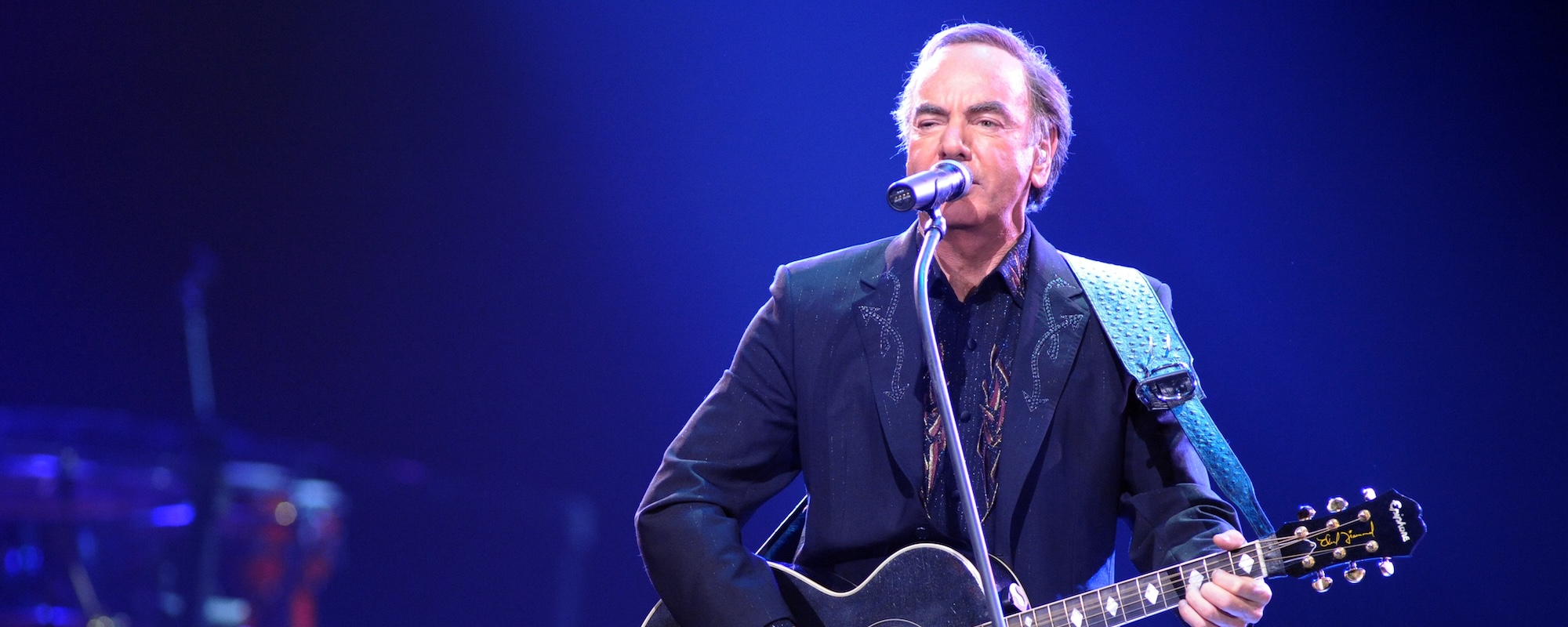

Along with a decades-long runs as a session player for Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Johnny Cash, Neil Diamond, John Prine, and Elvis Costello, among many others, Tench’s songwriting has also spanned more than four decades, from playing on and co-writing “Kind of Woman” with Stevie Nicks on her 1981 debut Bella Donna to his two co-writes with Don Henley, “Not Enough Love in This World” and “Sunset Grill,” from 1984.

Tench also co-wrote “Never Be You” with Petty for Rosanne Cash’s 1985 album Rhythm & Romance and the 2008 Mudcrutch track “This is a Good Street” and “Welcome to Hell’ from the band’s 2015 album Mudcrutch 2.

During the release of The Melancholy Season, Tench spoke to American Songwriter about some of the writers, artists, and more that inspire his life and lyrics.

American Songwriter: What are your earliest memories of writing music or lyrics?

Benmont Tench: I remember trying to write instrumental music when I was 7 or 8, because I grew up hearing stuff like Rogers and Hammerstein. Nobody wrote both words and music, and I concentrated on the music, but I wanted to write words, as well. When I got to college in New Orleans, I would ride on the streetcar—I had no car—and I’d try to write a song in my head on the streetcar. I’d get stuck, so I would turn to Raymond Chandler and writers like that for inspiration.

In my career in songwriting, a lot of the time, I wrote by myself, and some of those were covered in Nashville. I went to Nashville in the ’90s because I wanted to see how it was done, and that was where the old school songwriters still were, and I wound up writing with a bunch of great songwriters. I learned a lot, but by the end of my tenure as a staff writer, first with Maverick and then Walnut Chapple, I realized that, except for a couple of close friends in Nashville, I’d rather find it in myself by myself.

It’s all about learning things. If you aren’t learning, you aren’t living. I rewrite and fine-tune a lot … then, there’s the placement of a comma or an indefinite or definite article—it changes everything.

AS: Working with Petty in Mudcrutch and the Heartbreakers had to also elevated how you approached songwriting outside, whether solo or for other artists.

BT: When I met [Tom] Petty, he was really driven, and I watched him become a great songwriter. And he wasn’t a template. He was inspiring because of his belief in trying to write something catchy, not shallow, but something you could hold on to, and something that was lightweight, and not just a glib ditty.

AS: Who were some of the other writers you connected with most?

BT: Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler are direct. It’s funny as hell, especially Chandler. It’s fascinating, and the fact that they took a form like Pulp Fiction of “Let’s get really violent and dumb it down, but keep it moving and keep it vivid.” Those two guys went, “Yeah, but you can do more.” And you can do a lot more, like some of the great rock and roll writers who keep the simplicity of rock. To me, two rock songwriters who are overlooked are Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. People think, “Oh, there’s Mick dancing,” or whatever controversy, but if you get down to the words in the song and to their songwriting…

The master, for me, was Irving Berlin with those melodies and lyrics that go on forever, and everyone from Rogers and Hammerstein to Dylan, Harlan Howard, and Lucinda Williams. Lucinda is a marvel.

AS: And speaking of literature and songwriting, there are so many songs that read just like a poem.

BT: It is like a poem, but when you set it with the music, it just explodes into something else. In his [Bob Dylan’s] autobiography Chronicles: Volume One (2004), he says, “People compliment me a lot on the words, but there are instrumental albums of my music.” And it’s true. He writes beautiful, gorgeous melodies.

Reading is great for songwriting—and reading poetry. On this trip, I also brought [John] Miltonand I think I meant to bring some [John] Keats but forgot it.

AS: How has visual art also had a profound impact on your writing and performing?

BT: The cover of the album [The Melancholy Season] is a painting (“Fisherman’s Cottage” by Norwegian neo-romantic artist Harald Oskar Sohlberg), which I first saw at the Art Institute of Chicago a long time ago. We [Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers] would always play Chicago, and we would usually stay there, sometimes for a couple of weeks, so I would go to the Art Institute, and this painting really stayed with me. I always haunt museums on days off when I travel, and those visuals affect the music.

With the Heartbreakers, I remember one instance in particular. I didn’t have a brief unless the song was something like “Breakdown” or “Refugee,” and it has an iconic part. But otherwise, my brief was to hit the important hook and then play the song. So one night I’m looking across the stage and notice that Mike Campbell is wearing a shirt with a polka dot pattern with lines of different sizes. So I went, “Ok, I’ll play the shirt,” and it worked because it gave me a rhythm, and it was so much fun.

Art is so important, and this country, I hope, finds a way to hold on to funding in schools for art programs—visual art, theater, writing, poetry, music, sculpture, everything—because it is crucial. It’s crucial to the human soul.

There’s a reason why Bob Dylan makes iron sculptures and paints.

Photo: Daniel Knighton/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.