Adam Faucett doesn’t just sing songs—he inhabits them. The Little Rock native has long been a restless force. He blends folk, blues, cosmic howl, and rock stomp into something unmistakably his own. Critics have compared him to Tim Buckley, Cat Power, and even Otis Redding. But Faucett’s music isn’t about fitting into a lineage. It’s about carving out his own haunted, soulful corner of it.

Videos by American Songwriter

Over nearly two decades, he’s built a catalog that’s as raw and unflinching as it is beautiful. From the deeply personal More Like A Temple to the dark storytelling of It Took The Shape Of A Bird, Faucett has proven himself one of Arkansas’s most fearless lyricists.

And, he’s been legally blind since birth.

On his upcoming album, New Variations Of The Reaper (out September 19), he turns inward once more—into questions of spirit, survival, and the stubborn, strange work of being an artist.

Our American Songwriter membership asked Adam to shed some light on his process and inspiration for his upcoming album, and how being legally blind affects his songwriting and life as a musician.

Adam Faucett on Approaching Songwriting as a Legally Blind Musician and Recovering From Vocal Cord Surgery

Adam Faucett: I have ocular albinism, along with several of the men on my mother’s side of the family, including her father, my grandfather. Somehow, all of us legally blind guys in the family, through often inventive measures, have found a way to do whatever it is we need to do. People used to ask us how it was that we hunted deer successfully, and honestly, the answer to that is the same for everything else: we just find a different way.

There are two types of albinism. You got your Johnny Winter, and you got me. Meaning… not all albinos have the signature white hair. That’s the only difference. Albinism also comes with nystagmus—the left-right shaking of the eyes. Albinism robs the retina of pigment and the eyes of rods and cones. The eyes have to shake just to catch light, which the pigment and rods and cones do effortlessly for everyone else. The shaking of the eyes is definitely what alerted all the kids at school, and led to an early education in violence.

To be considered legally blind, you have to be below 20/200 in each eye. I have been legally blind for the entirety of my life. I don’t even understand how people see what they see, I can’t imagine what it’s like to be able to read a television screen or anything else that isn’t touching my nose.

A lot of people need glasses or contacts or whatever, but most people suffer from having misshaped lenses of the eye. Therefore, most people’s glasses are just a refocusing of an extra lens, if you will. My problem is much deeper and is not able to be fixed, only slightly helped by magnification. That’s why most people’s glasses look the same, and mine look incredibly thick. Mine are just big, longer-ranged magnifying glasses, and they’re also made out of a different material than the common plastic most people have.

I do drive my van around my neighborhood, but I don’t really do a whole lot of driving. If I don’t know where I’m going, I definitely don’t. That’s where my brother William Blackart steps in. I pretty much don’t do anything without him. He plays bass in my band. He drives me around everywhere when we’re on tour. Hell, we go halves on the merch. I couldn’t—and I wouldn’t—do it without him. When I am feeling like quitting music, he is the only one who will tell me that I really should reconsider. That’s probably because he knows the only other thing outside of music that I am halfway decent at is getting rides or being happily marooned.

My vision affects my songwriting mostly in the way that if I don’t have anything to play, then I’m out of a job. Being blind affects everything about life, music or not. I always have to get a ride, and I don’t remember faces well, so some people might think I don’t like them, when I probably just didn’t see them.

Most of my songs come from my actual life. I might switch some stuff around so it’s not terribly obvious, but my lyrics and songs are very lived in. For this new record, I set out to make the songs sweet in nature—or at least, that was the original intent. All of the songs, I believe, are pretty, but they were written through an almost unimaginable amount of loss and tragedy in my personal life, and then there was a pandemic as well.

I started writing this record when I couldn’t even speak because I had to have vocal cord surgery, so I didn’t even know if the songs were good or not. I had a cyst on my vocal cords, and that pretty much defined most of that year. And I couldn’t even speak to my wife across the table. I didn’t think I was ever gonna be able to sing again, or argue with anyone ever again. If you ever break your vocal cords, do your homework and find the best surgeon you can find. Luckily, everything worked out, but it took about nine months before I was able to play again. And then the pandemic hit a month later.

Become an American Songwriter member and get exclusive content, including access to the songwriters behind hit songs by Ed Sheeran, Bonnie Raitt, Morgan Wallen, Guns N’ Roses, and more. Plus exclusive content, events, giveaways, tips, and a community of songwriters and music lovers.

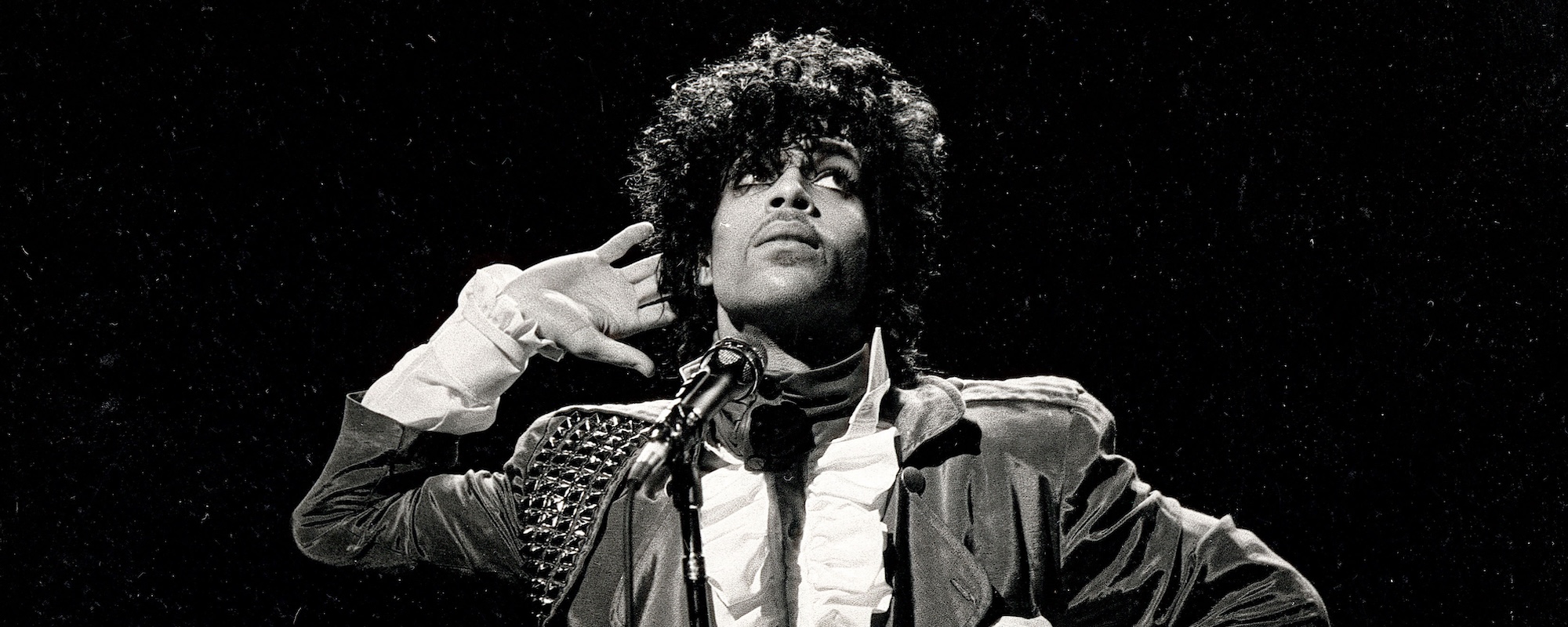

Photo via Adam Faucett

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.