Videos by American Songwriter

It’s awfully bold to suggest any one song has so affected America’s psyche that, nearly 75 years after it was first drafted, it still reverberates strongly enough to merit a textbook-dimensioned, 250-page book.

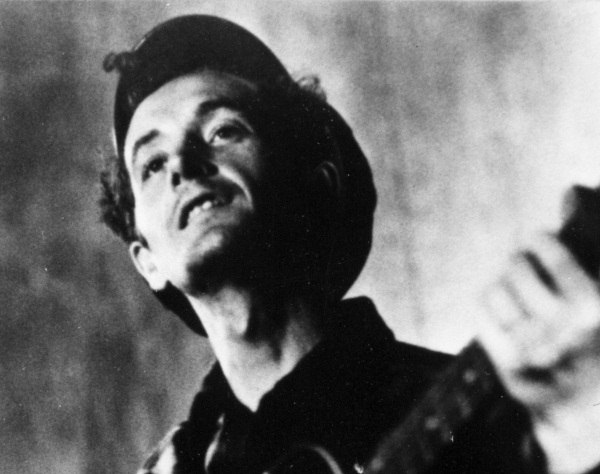

But this isn’t just any song, of course. It’s “This Land Is Your Land,” the Woody Guthrie sing-along that’s arguably more popular than our national anthem. Both an eloquent description of our nation’s beauty and, as originally written, an expression of scorn for those who don’t see fit to share it, Guthrie’s most famous song is an American totem, as timely now as it was when he first penned it, on Feb. 23, 1940, in irritated response to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” (His initial title was “God Blessed America.”)

In his new book, This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie And The Journey Of An American Song, Robert Santelli offers keen insights into its evolution from pointed diatribe to school children’s standard, and more recently, both.

Guthrie wrote it in a flophouse New York hotel, using the line “God blessed America for me.” He later changed it to “this land was made for you and me” and titled it, “This Land Is My Land.”

In the great tradition of folk music, the song morphed through a few incarnations. His original version, based on a song by Carter Family (“Little Darlin’, Pal of Mine”) referred to “Staten Island” instead of “the New York Island, ” and contained two verses he later lopped off, but which have been repopularized. They reflect his discontent with the Depression-enhanced economic disparity and greed he witnessed in so many pockets of the country.

As I was walkin’ – I saw a sign there

And that sign said – no trespassin’

But on the other side … it didn’t say nothin!

Now that side was made for you and me!

In the squares of the city – In the shadow of the steeple

Near the relief office – I see my people

And some are grumblin’ and some are wonderin’

If this land’s still made for you and me.

As Santelli reports, Guthrie’s first recording of the song, done for Moe Asch in 1944, included these verses. But hardly anyone knew that recording existed until the The Asch Recordings in 1997. When Guthrie began using the song on a radio show and published it in a mimeographed book of lyrics, it did not contain those verses (though his songbook contained a different verse: Nobody living can ever stop me/As I go walking my freedom highway …)

Guthrie wrote yet another set of lyrics for a revival of a Martha Graham Dance Company production, on which he had collaborated years earlier. One verse went: I saw my people and heard them singing/I heard them crying and saw them dancing/I saw them marching into their union/This land was made for you and me.

But it was music publisher Howie Richmond that put the song on its path to popularity. Alan Lomax suggested he offer various Library of Congress songs for publication in music-class textbooks to entice new generations into greater appreciation. Richmond offered publication rights for $1. With the growing Cold War, its patriotic overtones were easily accepted.

It fell to Pete Seeger and subsequent folk revivalists – from Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, John Mellencamp and Guthrie’s son Arlo to, Steve Earle, Billy Bragg, Tom Morello and so many others – to help Americans understand its dual intentions. And truly, what makes “This Land” so remarkable is that it makes a patriotic statement even as it chastises the selfish and powerful.

“This country was founded on the music of social change,” said Santelli during a speech at this year’s SXSW. Springsteen, he said, took Guthrie’s lessons to heart as he learned to balance American pride with socio-political criticism. In his own speech, Springsteen noted, “Woody’s world was a world where fatalism was tempered by a practical idealism. It was a world where speaking truth to power wasn’t futile, whatever its outcome.”

Springsteen also described the cold January day in 2009 when he stood at the Lincoln Memorial with Seeger, leading hundreds of thousands of Americans in singing every verse during the inaugural concert for the first black president in U.S. history. “When we sung that song, Americans – young and old, black and white, of all religious and political beliefs – were united, for a brief moment, by Woody’s poetry.”

Sure, any great folk song has the power to unite listeners – that’s one of their main functions. But this song is different. Until that day, Nora Guthrie couldn’t quite explain why. Guthrie, who oversees her father’s legacy, experienced that moment in a very visceral, personal way.

“For me, that was it. I looked up and I said to my father, ‘So that’s why you wrote it. And I was laughing and crying at the same time. Because the song made sense to me in the world, but not like that. And suddenly, I couldn’t think of any other song on the planet that would have been as good in that moment as ‘This Land is Your Land’ … I thought, ‘That’s it. My work is over.’ We’ve been to the mountain, we’ve seen the dream.”

As it turns out, there’s always more work. As Morello hops to Occupy rallies and artists like Neil Young pluck the song for new collections, she says, “Right now, Woody’s involvement with the country is really nice. It feels like a good thing for him to be involved in the conversation, when the conversation is so cuckoo.”

4 Comments

Leave a Reply