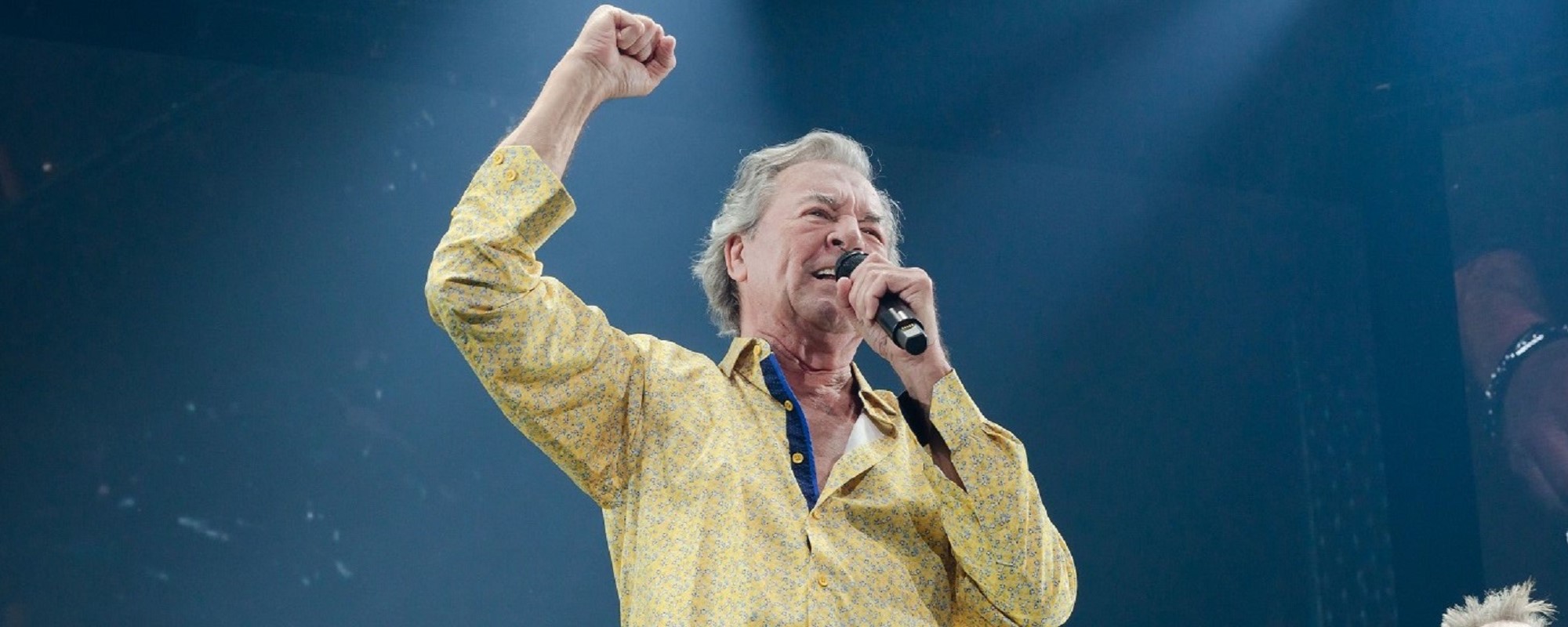

While walking along the beach with her children one day during the pandemic, Candice Night started paying more attention to the frosted stones hidden within the sand. Remnants of discarded bottles, jars, and other refuse, the sea glass was naturally repurposed by the ocean and smoothed out into softer edges by the forces of sand, waves, and salt water over many years. These “little treasures” also reflected the past 10 years of Night’s life and the songs on her third solo album, Sea Glass.

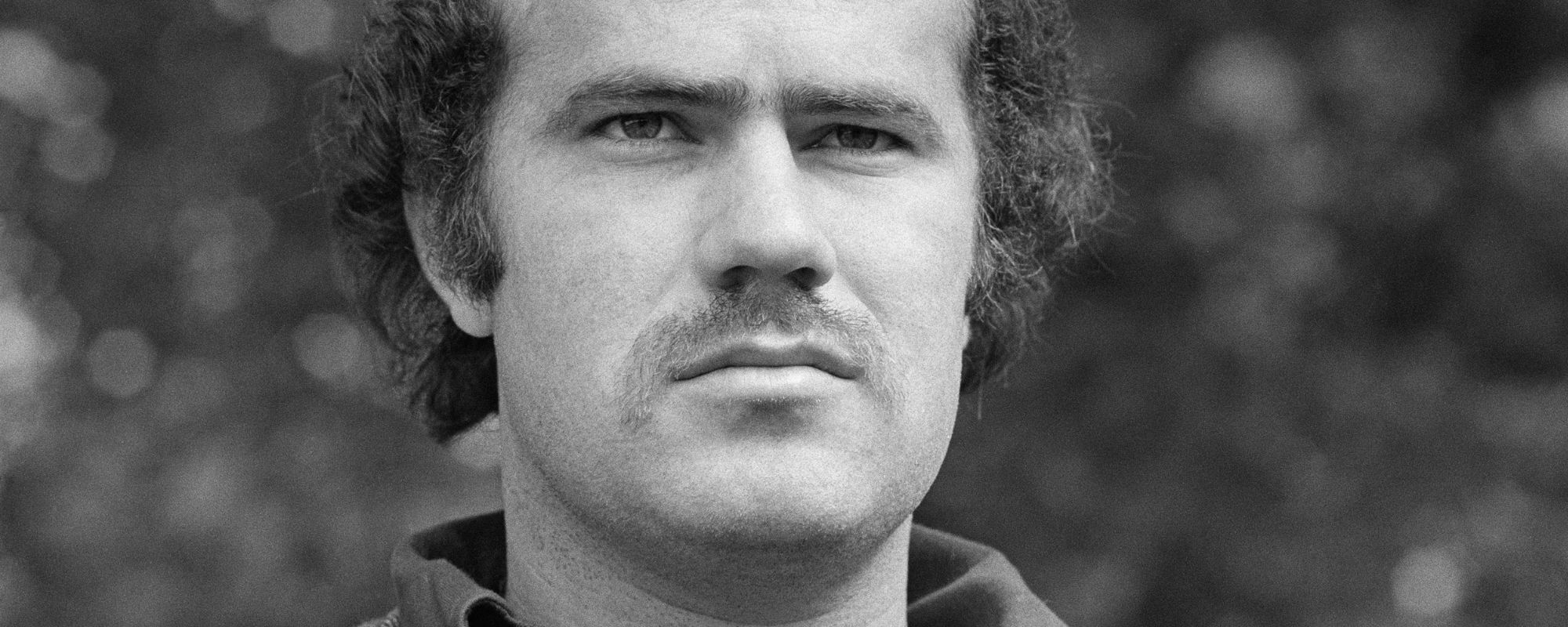

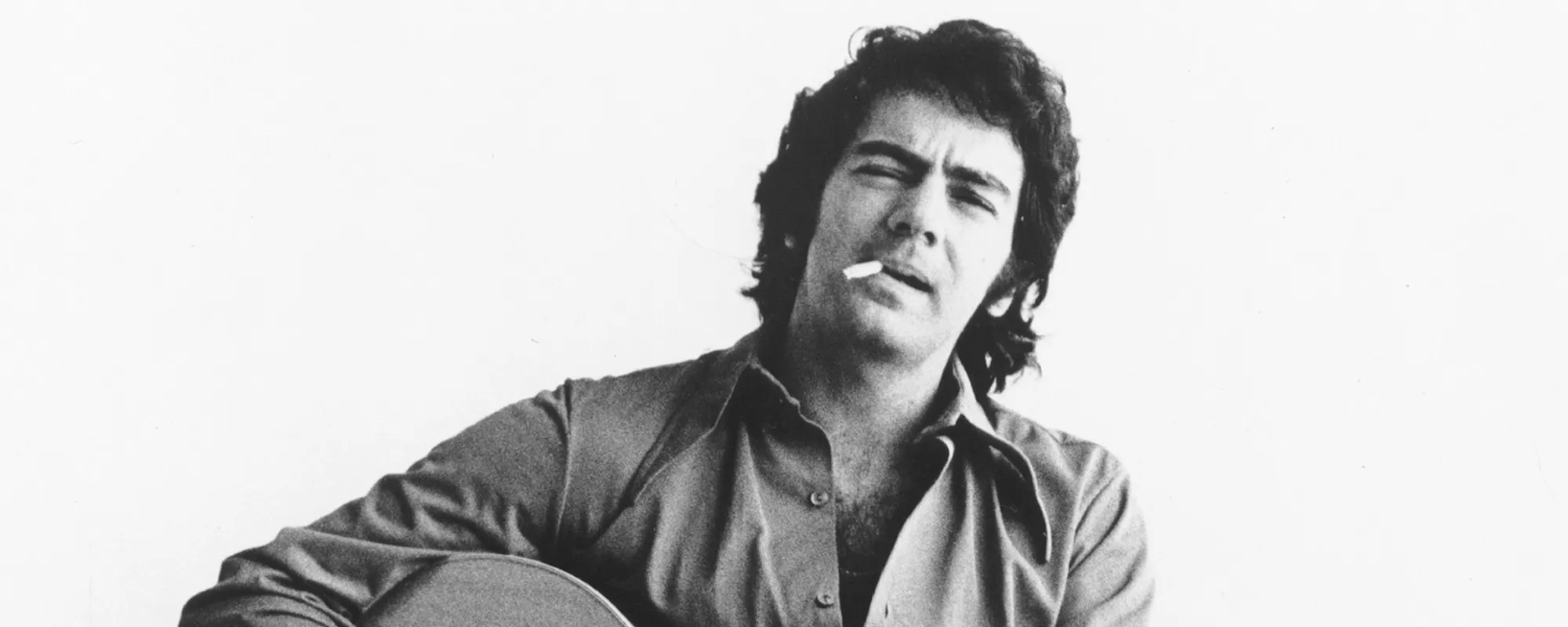

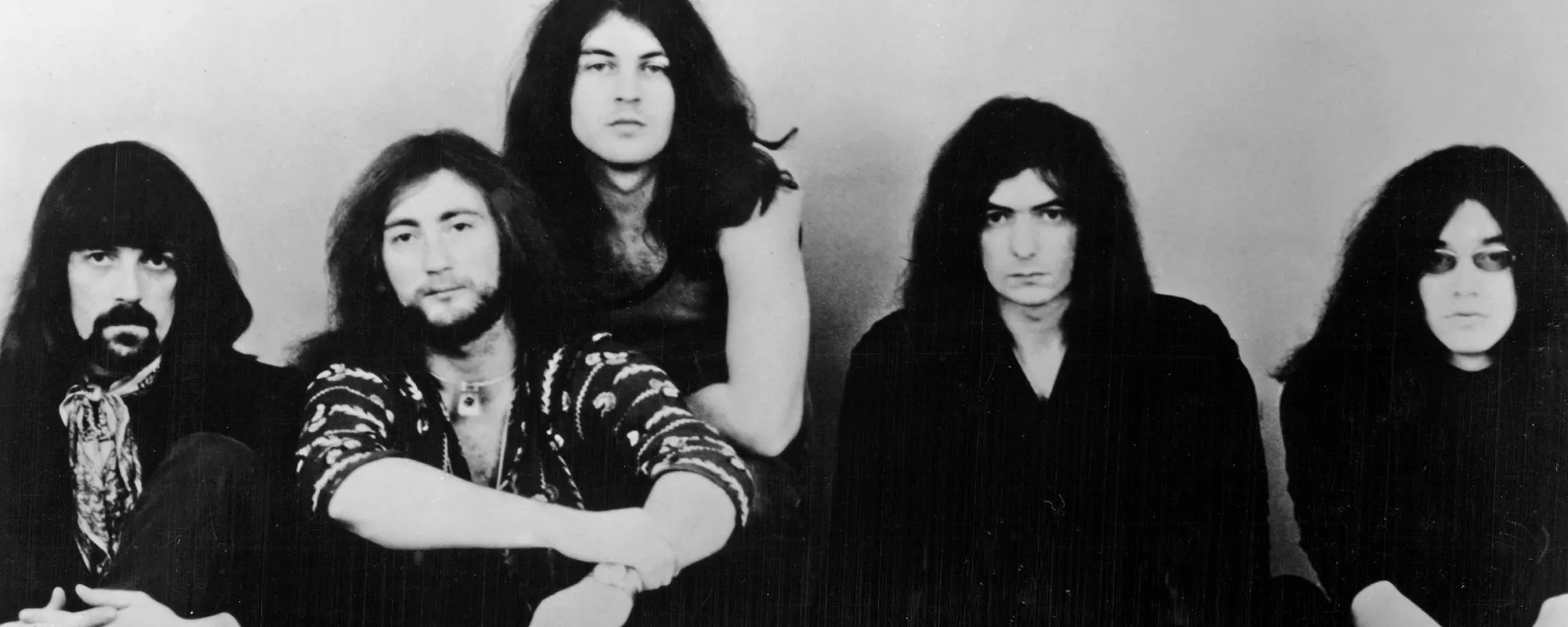

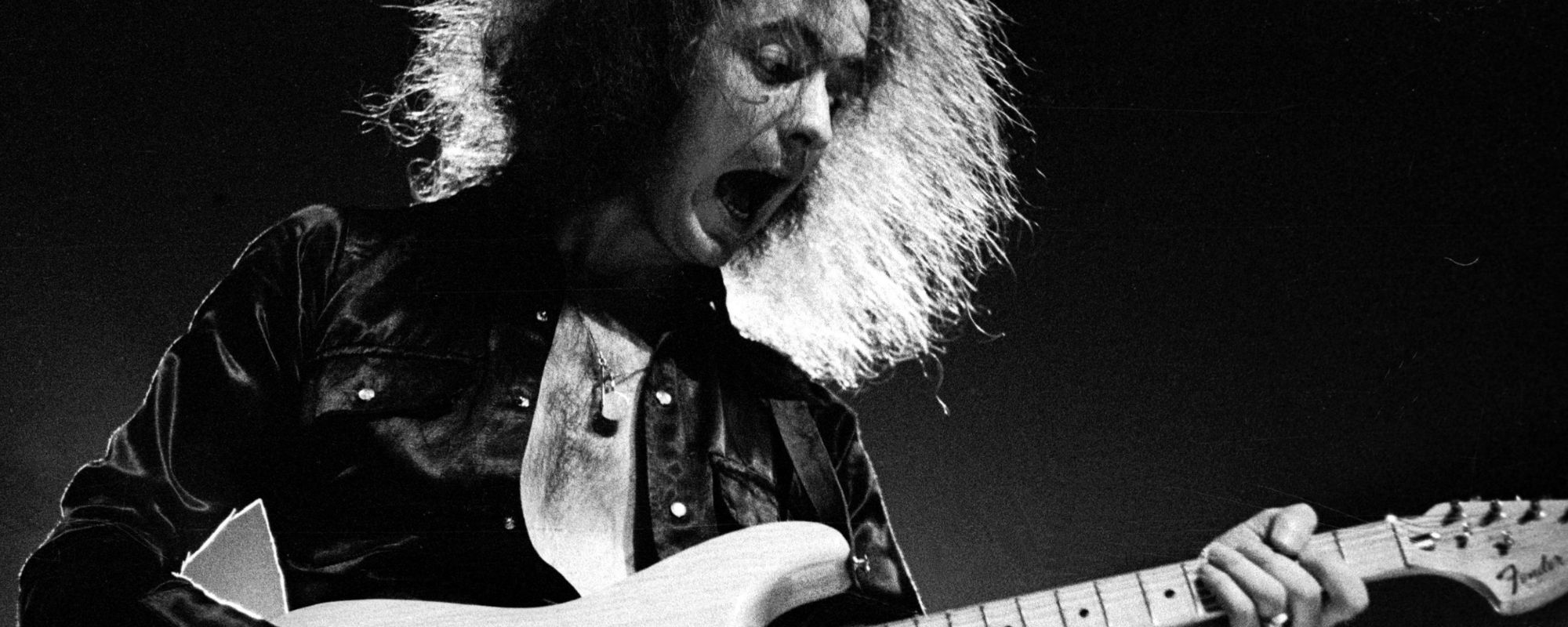

After releasing her Starlight Starbright and her tenth album with husband, former Deep Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, All Our Yesterdays, with Blackmore’s Night in 2015, Night faced the death of her father in 2018. The loss, coupled with the lockdown during the pandemic, all prompted different reflections for Night.

“I didn’t realize that each one of these songs would wind up being a collected piece of sea glass in my life,” Night tells American Songwriter.

From the opening title track, featuring Blackmore on acoustic guitar, and the more bluegrass acoustic march of “Unsung Hero (She’ll Never Tell),” and “The Line Between,” inspired by her father and the line between the year one is born and when they die, Sea Glass is a polychromatic glance at the different phases of life, mortality, and renewal.

Crossing genres, “Angel and Jezebel” brings in more country-rock tones along with its closing “Back Porch Version” at the end, and Night and Blackmore’s two children also sing at the end of “Promise Me,” an ode to motherhood—I’m more than a mom, I’m also your friend. Blackmore reappears on guitar on “The Last Goodbye,” which explores the passing of time, while the medieval folk “Dark Carnival” and “When I Want to Fly” call forth bonfires lighting up the night. Night’s balladry is relevant again on the mid-tempo ”Another Day” and a solemn cover of Nat King Cole’s 1948 Eden Ahbez-penned classic “Nature Boy.”

Videos by American Songwriter

“We go through so much in life, we break, we shatter, our pieces tossed and tumbled by forces all around us, smoothing our edges, teaching us lessons,” said Night in a previous statement. “And though some pieces may be lost, most return to be changed, different, worn by time, and yet, brilliant treasures in who we have become.”

Night spoke to American Songwriter about the making of Sea Glass, working with Blackmore, and how being a “closet poet” helped her songwriting.

American Songwriter: Your father’s death was a catalyst for many of the songs on Sea Glass. How did his death guide the album?

Candice Night: Everybody in my family, and all these different journeys in my life, are represented in these songs that accumulated over the past 10 years. And 10 years went so fast, but then the pandemic ate two years out of everybody’s lives together. But every time something really poignant in my life, something life-altering happens, I wind up getting a song out of it.

The catalyst was the death of my father in 2018, and the song “The Line Between” because he brought so much joy to everyone he met. He was a doctor who still did house calls with his little black bag that he had had for decades. And he did it until he was 80 years old, and would still go to people’s homes and work on every generation—the grandparents, the parents, the kids, and the grandkids. After his funeral, seeing the headstone and only seeing the birth date and the death date, that line between was everything. That line encompassed his personality, his individuality, how he had touched other people’s lives, the stories we had together, the laughter, the memories. It was all consolidated into a line, and it didn’t make sense. That line is more important than the two dates on either side.

AS: The song “Sea Glass” has a similar origin with reflections of family and the realization of passing time.

CN: When I wrote the song “Sea Glass,” I didn’t realize that each one of these songs would wind up being a collected piece of sea glass in my life. And I say that because I found this parallel between the human condition and pieces of sea glass. The sea glass actually wound up being our source of joy during the dark pandemic years, where I had these two little kids basically trapped in the house, quarantined from everything on the planet.

We were all going through it at the same time, and they were learning that their new normal was that you needed to be social on screens and go to school on screens. You couldn’t go and hug somebody. You couldn’t go to a restaurant, a concert, or a play date. And that becoming their new normal was not okay in my world. I was thinking, “How do I keep them in some mental state of being normal?” And whenever I need some healing, I always return to nature. Nature is an incredible healing source. It grounds you. It energizes you. It heals you. It mystifies you. It shows you the miracles every day, if you’re willing to see them, if you take the time to look or to feel.

AS: How did everything start taking shape around these walks on the beach during the pandemic?

CN: We would go out to get fresh ocean air, and they would get back to giggling and laughing again and running, skipping stones, and they started discovering that in the beige sand there were hidden little treasures, these pieces of what looked like sapphires or emeralds or amber, and you could hold it up to the sun, and they would illuminate and glow. We used to say that they were the gifts from the ocean. And we would look forward to doing that [looking for sea glass] every day. It became our source of joy. And as I’m walking down along the sand, I’m thinking, “Isn’t it strange that these broken bottles, these pieces of glass are something someone would look at as trash.” They were tossed around, tumbled, their edges were softened, and when they returned, they became treasure. They went from trash to treasure.

It’s interesting in the human condition, how we break down. We have all of these things in our lives that we lose. We shatter. Even though our edges get softened through time, we return to where we were; our roots are still strong and stay the same. It’s really about finding that glowing, treasure-hunting piece of joy that illuminates your soul, where you can still say, “ I went through this. I broke, and I continue to break, and this is not the end of it, not the end of me.”

We just have to keep going and try to find joy in the moments. When I started looking at all these different songs that I accumulated over the last 10 years, each one of them is its very own piece of sea glass. So it’s the collection of all those pieces of sea glass that hopefully will help people find some joy, some healing, and some treasure.

AS: Sea Glass naturally became a family affair with Ritchie appearing on two tracks, and your kids also sing on “Promise Me.” What’s the story behind that song with your kids?

CN: I told my kids, “Look, you only know me as mom, but I was a whole other person before you ever met me, and you guys made me a mom. So here’s what’s gonna happen on this journey. We’re all gonna make mistakes. I’m gonna make mistakes, too, as a mom. You’re going to make mistakes, but I’m going to be there for you. I’m going to help you pick yourself up. I’m going to stand there with you. You’re not always going to like the answer or understand why I tell you things that I do, but this is the role that we’re in, and I hope that we make many memories together, have laughter together, and that we look at each other as friends. I’m the one that you want to come to if you have an issue or a problem, because I’ll always be here for you. But I’m always going to be a mom first.”

AS: How did the Nat King Cole cover end up on the album?

CN: My dad was listening to this [era of] music when I was growing up in the kitchen on Sunday mornings, dancing with my mom. They also listened to the big band—Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw—stuff that was on the radio from the ‘40s. We’d sing doo-wop songs together on every road trip. I would make signs and put them out the window, saying, “Please help me. My parents are trapped in the ‘40s and ‘50s.” We were singing to each other, and you look back and think about what great childhood moments and memories they were.

When my dad got sick, he was fighting cancer, and we were working on Blackmore’s Night stuff, and I’m like, “What can I give to my dad?” So I recorded those two songs (“The Line Between” and “Nature Boy”) for my dad. And when I brought it to him for his birthday, he put it in a little Walkman, put his headphones on, listened to the songs, and went, “Oh, that’s nice,” and walked out of the room. He came back a couple of minutes later and went, “Wait a second. Was that you singing that?” Then, he didn’t take it off his head and was listening to those songs for the longest time. I couldn’t even listen to those songs because they were so personal. It was such a personal thing for me to do those and give them to my dad as a gift.

And then once I listened to that Nat King Cole song, I really did love the interpretation. You can never duplicate Nat King Cole, but the interpretation, and how it became so haunting … I tried to see it from a different perspective. It took me a while to listen to it again, because it was so close to my heart.

AS: Thinking back to first writing for Rainbow on Stranger in Us All (1995), and later for Blackmore’s Night, and your own solo albums, how has your songwriting changed throughout the years?

CN: When I was in school, I wanted a career in music, whether it was music journalism or working for a radio station or a record company, but I never thought I would be the one creating it or being on stage performing it. That was out of my confidence realm. And I was always a closet poet. I’d have books of journals and poetry books—even my school books were covered with lyrics. So when it all started, it felt like a natural evolution. When I met Ritchie and he was recording Stranger In Us All, he told me that they were having some difficulties coming up with lyrics, and that he was going to fly in a professional lyric writer. Then he said, “Would you like to try, because I see you writing in your book all the time?”

He had played me the backing track, and during that hour and 15 minutes on the ferry, looking out at the water and just feeling that fresh air on my face and the sun on me, I wrote 14 verses. Then, I continued during the drive up to Upper Brookville in Massachusetts, and I handed it over to them. The producer looked at it and went, “Great.” He circled four verses and said, “This is the song … cancel the plane flight for the other lyricist. We don’t need them. We’ve got one now.”

I loved delving into those different perspectives, philosophies, and viewpoints. When I was writing for Rainbow, I had to write as a male rock and roll singer, which is from a more aggressive, angrier perspective. From that point, the craft of songwriting and lyric writing just intrigued me. It inspired me. It became everything to the point where I had so many lyrics backlogged and asked Ritchie for more music. I had all these words, I needed to set them to something and see them come to life. He said he was busy and suggested I write my own songs, so I sat at a piano, and I started coming up with melodies, and the melodies fit the words, and everything came out all at once.

Then “Black Roses” from Reflections (Night’s 2011 solo debut) came out, and “Alone with Fate”… I channeled something, but if I try to force creativity, I shut down. I can’t force it. But when all those stars align, everything just wants to come out when it’s ready. I don’t know if anything has really changed, except for the experiences that you go through and the constant evolution of being a human. During your journey in life, consciously, nothing’s changed. Experiences lead you down different paths and can give you different ideas and perspectives. It’s just what life does.

Photos: Kristin-Metzler

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.