This is Part II of a two-part series. You can read Part I here.

Videos by American Songwriter

AMERICAN SONGWRITER: On the demo Paul made of “Bridge Over Troubled Water” he sings it like you. Your range, your style. It showed that he always wanted you to sing it. He wrote it with your voice in mind.

ART GARFUNKEL: Yeah. I’m sure he did.

That shows how much reverence he had for you and your talent. Here’s his greatest song. Right away, he thinks, “Well, Artie’s got to sing it.” That was generous, wasn’t it?

Yes.

Also a good choice!

[sings] “The long and winding road that leads”-

[Laughter] You recorded “Bridge” on both coasts. The story goes that he wrote only two verses, and that you and Roy Halee both told Paul that it needed a third verse.

That’s correct. That’s definitely correct, once and for all. Put that on the record. I know the truth. That’s right. I heard that. As a record producer that thinks about the structure of a record, I wondered is this one of those two minute and 50-second babies, or is this one of those four minute and 20-second “Whiter Shade of Pale” kind of records? Those are bigger ones. They aim higher.

And I said, “Aim higher, boys. Roy, Paul, aim higher. This is a longer, bigger record. This is a four minute and 20 job. It needs a third verse.”

And Paul was thinking of it differently ?

He was thinking of it as a three minute job to him.

Then did he write that third verse quickly? That’s unusual for him to write a verse in the studio.

Yeah, once he bought the idea. “Okay, let’s see if the third verse doesn’t make it a pop song with an exciting third verse. Artie, you want the third verse to go big, huh?”

“Yes, I do.”

“All right, so the third verse should be a pop song that brings it on home, like a pop song?”

“Yes,” I said.

[sings]”Sail on silver girl.”

And once he did that and I harmonized it, then it started sounding like a pop hit, if I dare say those words. He got the point, and we tried to be a classic version of a hit record that’s opening up at the end. The production’s getting bigger. The strings come in. The bass starts glissing, if you know that word, up from the bottom.

There’s two drummers. Once drum is doing toms, and the other is kind of rumbling along. Attitude is everything. It rumbles along. There’s classic strings. There’s no girls. There’s a lot of stuff starting to slip in, one at a time. And when all the arrivals have set the table, suddenly, Artie is not alone anymore. He’s got Paul harmonizing with him, and both of us are doubled. We sing on top of ourselves.

[sings] “Sail on silver girl.”

It happens at that moment, and the record expands.

[sings]”Sail on by.”

It’s a lot of fun to see that all slipping in.

I remember like yesterday the first time I heard it, in a poster shop in Chicago with my dad after going to Sunday school at temple. Immediately I knew it was you, but I stunned. I felt it was so beautiful–

Yeah, I see what they’re doing. They’re trying to be religious, these wise asses.

My dad bought me the 45; with “Keep the Customer Satisfied” on the B-side. And that is all I listened to probably for a month.

[sings] “Sail on silver girl, sail on by. Your time has come to shine.”

When did you realize it’s Paul and Artie, and they’re going into two-part harmony here? Was that instantly apparent?

I don’t know if it was instant, but I got it. Because that’s a wonderful sound. Suddenly, there’s those two voices together. The old friends.

Yeah, yeah.

[sings]”Your time has come to shine. Your dreams on their way. See how they shine. If you need a friend, I’m sailing… ” The key drops out right around there.

[sings] “Sailing right behind. Like a bridge over troubled….”

And now it really augments.

[sings] “… water. I will ease your mind.”

And now I pick my chin up and look even higher.

[sings] “Like a bridge” …

And Paul has left the record. He’s getting coffee now.

[Laughter]

[sings] “Over troubled…”

And I’m trying to breathe and go for higher notes than I ever went for. I’m really aiming. I let my intentions aim higher. And lo and behold, there it was on the 750th take.

[Laughter]

I’m glad you laugh, because it wasn’t that murderous, but it was a manner of work. Work, work, work, aiming high.

For the vocal, you went back to New York and you did your vocal in New York?

I got that high note at the end of “Bridge” in the first attempt in San Francisco, I believe. I’m not positive anymore about these things. But it happened in the first of many takes. There were probably eight different attempts that I went for the vocal of “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” The first one was in San Francisco, and I got the ending. And that’s what inspired us, me and Roy and Paul. It was terrific to have that last part done and to be satisfied.

So that was done before the rest of the vocal was done?

Yes, it was.

Paul wrote it on guitar, and most of your records had guitar. But it became a piano song. Was that always the idea, that piano would be the main instrument?

From the moment the song was written, when Paul showed it to me, he showed it to me on guitar. He works on guitar when he writes. But he showed me his intention was piano, and early in the game, we started putting it on piano.

With Larry Knechtel on piano. I heard that it was a long process to get the piano part right, and it was you and Larry who worked out that part.

Yes. We were in Muscle Shoals [recording studio in Alabama]. Paul said, “When you finish your verse, how do you turn around to get ready for the next verse? On those turn-arounds, you work that out.”

Then I remember me and Larry deciding how long they would be, just how to work that out. So it was a piano-vocal thing.

You and Paul recorded Sam Cooke’s “What a Wonderful World” with James Taylor. Do you remember what led to bringing James with you and Paul on that?

Well, before the song came, Paul and James and me said, “Let’s do a trio thing.” James loved us; we loved him. It felt like a natural thing for us to do. I’m not sure who produced it. Was it Russ Titelman? It’s the kind of thing he would have produced. (Phil Ramone produced).

And then we worked out our parts in the most natural way.

[Sings] “What a wonderful…”

I have my own love of that in that theme. It fell into place really lovely. I love how natural it was.

Is it me slightly in the lead with the two lads backing me up? I tried to sing it that way.

That’s how it was actually credited. Art Garfunkel with Paul Simon and James Taylor.

That’s how we did it. That’s how it felt. Both guys were trying to say, “Artie, step up.” And I did. The second verse, you notice it’s a lot of fun for Paul and I to both step forward.

Yes, you’re giving me such a nice gift, Paul. Yes. “All right, don’t be afraid. You’re the lead in that song.”

That second verse has a lot of hammering the vocal on. It’s Simon and Garfunkel being very Everly Brother-ish. Very unapologetic.

It’s nice. It hammers the notes on, and it’s loud.

Was Sam Cooke an influence on you?

Yeah, he comes before me. When I was first starting to learn how to sing R&B, Sam was already having hits. He was the smooth singer. He was the one who opened his throat and let it out. Sam Cooke had a lot of wonderful power in his singing.

You see, I do machinations and tricks and restraining tricks with my vocals. But Sam really knows how to let power out through the vocal cords.

[Sings] “You… send me…” He opens his throat more than I do.

I worked with Paul on his first boxed set [Paul Simon 1964-1992], which has a lot of Simon & Garfunkel on it. He asked for suggestions of what songs to include, and I kept bringing up “Overs,” from Bookends, because I love that song —

Yeah, he doesn’t respect it enough. “Overs” is worth looking at. Good for you.

It’s such a special song, and so essentially Simon & Garfunkel, with you taking the bridge on “time is tapping on my shoulders…” That is a classic moment.

So I kept pushing for it. But finally he said, “Look, I’m not going to do ‘Overs’.” But I never understood why. What’s the problem with “Overs”?

Oh, he didn’t give you an answer?

No. But I didn’t ask why. I was a little intimidated —

[Laughs] I can just hear Paul. You’re making me miss him.

[Laughter] And it just makes you want to go, “Why not?”

And all you get is, “I’m not even going to explain. I’m going to be pissy about this subject. Now, leave me alone.”

I’ve always wondered why. Is that song too personal for him?

Why doesn’t he like it? No doubt, it’s something to do with me.

[sings] “Why don’t we stop fooling ourselves? The game is over, over, over.”

So all of our fans, the Simon and Garfunkel fans, go right to us there.

[sings] “No good times, no bad times.”

Paul probably doesn’t like that the spotlight is driven to Simon and Garfunkel there.

[sings] “There’s no times at all. Just the New York Times. Sitting on the window sill, by the flowers. We might as well be apart. It hardly matters, we sleep separately. And drop a smile passing in the hall. But there’s no laughs left because we laughed them all. And we laughed them all in a very short time. Time is tapping on my forehead, rattling the teacups…”

Well, who knows what Paul Simon feels about this piece of songwriting now that it’s dated here? Because it’s Simon and Garfunkel-reflective, and it dates poorly.

[sings]”Rattling the teacups, and I wonder, how long can I delay? We’re just a habit like saccharin. And I’m perpetually feeling kind of blue…”

It’s `habitually’ —

I’m missing Paul. How nice the songwriting is. It’s really good writing. Look how the rhythm of the syllables falls in a nice syncopation. It has a bounce to it.

[sings] “And each time I try on the thought of leaving you.”

Now, that’s pretty Simon and Garfunkel, isn’t it, Paul?

Yes. And that’s who it was —

[sings] “I stop, I stop, I stop and think it over.”

It’s a career statement. It’s coy. It’s playing games with the listener and going, “You know who I’m stopping and thinking it over about.”

Well, even being obsessed with you guys, it never occurred to me that it was about you. It seemed like he’s writing maybe to Peggy, his first wife.

Well, yes, it could be. I guess it’s 50-50. Paul always loved that. “If I write something,” he would say, “and you don’t know which way to go, it could be 50-50, I like that a lot. I leave it right there.”

Your first solo album was Angel Clare, which is an amazing album. Such a rich choice of songs, and the production by you and Roy Halee is remarkable.

That is what you did in those days. It’s part of the era. We put a lot into each record.

Roy and I made that album in Folsom Street, on the other side of Market Street in San Francisco. It’s the funky part of town. There was a recording studio there. I used to get up in the morning and go down. I was married to my first wife then. And Roy and I would make my first solo album, and I was happy to see it develop.

The song choice was great, with songs by Jimmy Webb and Randy Newman. But also the amazing Jobim song I’d never heard before, “Waters Of March.”

I thought I did good, Paul. I like my version of it. It’s so unlike everything I’ve done. I don’t know if you see what I’m trying to do. But I’m just playing with vowels and consonants. It’s like a man is dying. And as he’s dying, the kaleidoscope of everything on earth while he was alive is spinning around before him.

It’s all about the 360 degrees, Paul. There is everything. The sprinkler on the lawn. In that childhood, the cloudy day when it burst into rainfall.

[Sings] “A stick, a stone, it’s the end of the road/It’s a sliver of glass…” Oh? Is it a sliver of glass? Yes! It’s everything! It’s 528 more things! And some verbs and some rhymes.

[Sings] “a truckload of bricks in the soft morning light…”]

I’ve been I’m having great fun with producing these vowels and consonants, and using the vocal chords to touch lightly on the sounds. So it will be delightful. Playing with the velvetyness of these sounds.

Yeah, that is like one of your vocal signatures, the way you caress words. This song, though, is much lower in your range than usual, yes?

Yeah. It went way down. That’s right.

Because that is where Jobim sings it?

Yes. I’m inspired by him as a writer. I tried to see if I could do it down there.

His version is looser with the rhythm that how you sing it. You’re more in the pocket –

What a compliment, I was tighter than the great Jobim.

What led you to that song?

I think I got it from Paul Simon. I feel like it was Paul who said, “Do you know that song? You would love it.” And I tracked it down and I loved it.

It’s beautiful. I remember the lyrics came then as a kind of a revelation. His use of language and specifics was so different. I didn’t know you could write a song like that.

You imagine that you’re dying. That’s what I did when I was on the mic. These are the final breaths, Paul. He’s exhaling his last 419 breaths and as he’s dying, there’s that snowfall and there’s her touch, it’d be all in the everything, and it’s spinning around him and he’s embracing and loving, the whole thing. Loving the whole thing, loving the whole thing. Loving… the whole thing.

It was very fun to sing, you just embrace it all.

From ‘Angel Clare.’ |“And the riverbank talks of the waters of March,

it’s the end of the strain, it’s the joy in your heart.”

Your version of “Traveling Boy,” by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols is delightful.

When I think of that song I think of trying to get up at bat and hit a

home run. So he gets to bat and he hits the ball square, dead on, puts a lot of force behind the swing.

Don’t apologize. Hit it dead on. That was truly my intention.

When interviewing Paul Williams, I asked about this one, and he said, “Garfunkel recorded it beautifully. I usually close my show with it. I ripped off Garfunkel’s arrangement and used it for myself.” Also that the song laid around for a long time and then you saved it. and you saved it.

That made me smile right now, that’s nice.

What took me to that song? Was it Roy? Here’s Roy and I talking about this first album and we’re looking for material. I don’t know.

You did “I Shall Sing,” by Van Morrison –

I don’t like that. I don’t like “I Shall Sing.” I’m embarrassed by it. It’s too pretty. It’s too prissy. I find it too pretty. I wish I did it more distorted, more funky. It’s not right. It’s feminine. It’s prancy. It prances.

Rock and roll should not prance, Paul.

[Laughs] “All I Know” by Jimmy Webb, was the single. Jimmy was, of course, thrilled you chose it and also how you produced and sang it. It is stunning. He said that you asked him to play some songs, and he played for three days, every song he had, And in that you found “All I Know.”

Yes. That’s how I recall it. We picked up on each other after years of not seeing each other and hanging out, and he was on the West Coast and so it was.

He was the next best thing to Paul Simon I found in the writer’s world, Paul. Once I started hanging out with him over the keyboard, then I saw Jimmy Webb has really got a chord change sensibility that fits me.

The chords he chooses, the inversions, how he goes from this to that chord, makes my appetite for singing come alive. I want to do these: “Show me this, Jimmy. Show me that. What’s the lyric here? What if I change this one thing, are you amenable to it?”

This is me and Jimmy back in the sixties… Seventies? It’s exciting, very exciting.

His piano playing, the way he plays these open chords, he has his own style of chord interpretation. It’s very blue skies, open, spacey. He’s Oklahoma.

Do you remember when you heard it if it was obvious it was the one? Or were there others in the running?

It was, “That’s the one.” That’s a solid, good song. There’s an A-pluser. That’s what I felt.

[Sings] “I bruise you, you bruise me, we both bruise too easily, too easily….” By the time you’re up to the fourth line, I was thinking, “This is a first-rate pop song.”

[Speaks lyric] “We both bruise too easily to let it show/I love you and that’s all I know.” And that’s the first verse. Well that’s pretty nifty.

And then comes… this kills me, Paul. If I could just take a moment? Then comes the second verse and it gets really blue and melancholy and it just slays me.

[Sings] “All my plans have fallen through/All my plans depend on you…”

Forgive me, I’m singing so awful. If I were in good voice, I would be destroying you with how powerful this part is.

[Laughter]

[Speaks] “…All my plans have fallen through/All my plans depend on you/Depend on you to help them grow/I love you and that’s all I know…”

Now that you’re gone, baby, my whole appointment book is empty. Everything I had wanted to do has gone blank.

It’s got a power, and when the love affair is gone, life has been turned off.

Yeah. That one has simple, churchy chords, but the melody just keeps ascending. So for your voice, it is magical.

I think the lyric takes over you. The power of those words is powerful. “All my plans have fallen through.” I see an appointment book, oh,m that’s gone blank, like all my plans depend on you, depends on you to help them grow. I love you. When the singer’s gone, let the song go on,” and here you’re meant as a singer, you’re supposed to leave the stage. It’s perfect. You’re turn your back on the song and you let the piano player carry it.

His first solo hit, from ‘Angel Clare.’

“When the singer’s gone, let the song go on…”

You doing this song as your first single – and it was a hit – really annointed Jimmy Webb as an important songwriter. He already was important, but this expanded that in a big way.

Well, can I say to this? That’s what I thought I was doing. I respect my own choices and my own albums. I respect my own choices and I feel I followed my tastes and I knew exactly what I’m doing.

And now you’re saying, “Well, I was on your track, Artie.” Well thank you, Paul.

You’re welcome, Artie.

I thought I overdid it, Paul. I thought me and Roy Halee went to town on the production with all them strings a bit too much. It has a crescendo, and then it calms down production-wise, and then it has another crescendo.

Two humps like a camel. I didn’t like that. Now this is the producer talking, me. I thought it shouldn’t have two humps.

You’ve recorded more Jimmy Webb songs than anyone there is, except Jimmy. I asked him about you, and he said, “He’s just got the cleanest, most elegant line. He’s a real artist in the true sense of the word. He’s very particular about the way he records and what he does.”

[Pause] I’m good, Paul. I love working with Jimmy, I wonder what he’s up to now. I’ve been playing The Animals’ Christmas, you should check it out. If you have a copy of it anywhere around the house, check it out. It’s a lot of fun to listen to, it’s cool. It’s good.

Listen to it. Watch how the “Carol of the Bird,” song number nine, takes over and is sequenced. It comes out of song eight and goes to song ten. Watch that sequence happen. Whoa, it’s fun.

Your version of Jimmy’s “Wooden Planes” is wonderful.

It’s sung as if you have an emotional catch in your throat all through the song.

It’s a style. You give yourself a catch in your throat, “Sorry folks, I can’t carry on. I’m emotionally overcome.” It’s a style, it’s an actor style. Only a phony baloney would do this style. [ (singing) you hear me trying to have a catch in my throat, Paul?

Yes. I was listening to that vocal today and appreciated how much character is in each line, like the way you pronounce the word `propellers.’ You propel the lyric in an amazing way.

I’ll take the compliment, we’re both saying the same thing in different ways. For me it’s a case of making it seem like just a catch in your throat and you’re a little overcome with the emotion and the idea of the lyrics. That’s what I think I’m doing, phony that I am.

I checked out the credits on this album and others, and was amazed by the musicians. You always had some of the best in the world. You had jazz legends Paul Desmond and Joe Farrell on Watermark.

I played with great people. What a life I’ve had, Paul.

They took me to town. They really showed me another thing. They make me feel good and that I’m on the A Team and I am. I put my cans on and get in my vocal booth and I put out this nice Artie Garfunkel sound. And sometimes the fact that they’re so good just tickles me and I can hardly sing. It’s so much fun because they’re so damn good and the mutuality starts happening in the earphones and I can’t do the vocal, I’m laughing. I’m tickled by it. Leaving the earth and stepping into the air for a little ride.

When I think of the great harmony singers of our time, I think of you, and also David Crosby is up there with you —

I was hoping you’d say that. He’s very subtle. He’s in the pocket. He’s the voice in the middle of the arrangement that you hardly notice, but it cements the harmony beautifully. He makes a great choice and he sings it in with a zen magnificence. He’s invisible, but he puts the harmony in the middle.

He’s always the middle guy. If you were to extract his harmony line. You go, “What a weird thing!” But it is the cement line that makes it work. He’s a real unsung hero as a harmonist.

Yeah, it’s the glue between the two parts. You’d have to be really good to sing that part.

I’m glad you see that, I’m glad you see that. He’s not appreciated enough.There’s something zen in his vocal production, it’s so easy.

Often your harmony parts were like that, too, that if you really analyzed your part, they’re not always normal parts, but they’re magical. They work so perfectly. How would you create those?

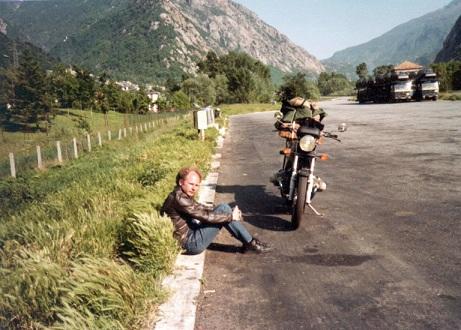

I used to take my motorcycle and be out there in Switzerland and drive around and in my cans would be a record I’m working on with Roy and Paul and there’s his part laid down and I’m looking for a harmony part, and I’m on the bike.

You know there is this Swiss Alps pass and I’m singing in unison with Paul and I’m trying to be perfectly dead right on top of Paul’s part, unison and out my eyes is Switzerland and this beautiful mountain pass.

I’m driving carefully, I’m using my rear view mirrors, and as I’m singing and getting to know exactly his phrasing, I get to know the song better and better and I started thinking of upper harmonies because he’s the lower a baritone, he has left all the higher notes for me. So I started sailing off first.

And if Paul was Don Everly, what would Phil do? If Paul were the lower part of simple, simple two-part harmony, what would the upper part be? That’s basically the alphabet, the most simple version of looking for a harmony.

So I go there and now I’m doing thirds above Paul and I’m playing around with harmony parts. “What’s the easiest motion? What allows me to move my part the least, which is to say what’s most natural and it’s in its motion?” That’s what Bach would have done and why not move the least? And if, and if it’s gluey and lovely and smooth, I’ll probably go there and I’m writing my harmony, Paul.

And I’ll stick with that if I think the lyric has taken me to a special place. In the second line of the second verse, wouldn’t it be nice if I was a little tricky and then sailed off with a surprise? “Look at that note. He didn’t go high, Garfunkel went so low.” Weird, but it works. Look how it works with the lyrics. These are games you want to play.

These are great questions. All I have to do is give my Simon and Garfunkel career its proper importance, and then I appreciate your whole interview, Paul.

I’ve always wanted to ask you about your long-distance walking; you go somewhere in the world and walk for days and weeks, all alone, across a country. When you are in the midst of one of those long walks, what’s going on in your mind? Seems like that could be lonely and maybe not fun. How did you experience it?

I like my mind. My mind is amusing to me. I think a lot about stupid stuff. I commune with my head. I remember stuff. I think about my wife a lot. I think about my past. I think about my career. Oh, I enjoy my memories and what’s going on in my head.

Really? I’d wondered, because, as you know, not a lot of people have done these long walks — .

I don’t see why not. I don’t get it. What’s wrong with them?

Nothing’s wrong with them. But nobody else does that. How did you get started doing that?

I originally traveled by freighter. I really like my own company. I took a freighter across the Atlantic Ocean a few times, brought my books. I love my reading, and I was writing. I’ve gone across the Atlantic a few times, so I tried the Pacific once. It was great. You take these freighters, They only have six different people in their six cabins. They’re school teachers. And there’s me.

Then I try going across the Pacific. That’s an eight-day trip. I land in Yokohama, not far from Tokyo, and I think, “I’m going to see Japan in my own sense, like a child. I’m going to practically crawl across the country, but I’ll be upright. I’ll carry a notebook and a little bit of change of clothes, but I’ll keep buying.”

So I’ll carry a little bit of stuff, a T-shirt and socks. But I think I’ll walk across the country and see Japan as a walker’s point of view. And I bring my book, and I start doing it. And it works. It’s fascinating. It’s me.

I’m a rock star. We do things in an odd way.

You said to create harmonies. you learn to sing the song in unison to get the phrasing right. Which is what you did when we worked together; you match the phrasing with perfect precision.

Yeah, you get the lead down first. Before you just fly away. You first learn the original moves.

Doing that makes all the difference; the precision with the soulful sweetness of your singing combined. But it doesn’t have to be that good, you know. But it’s why you’re you. You take it to a whole other realm.

I’m an old pro, I can’t help it. I’m an old pro.

I have fallen into habits of professionalism. I can’t get out of it now.