On November 7, 2016, Leonard Cohen died, yet his passing was somewhat overshadowed by the consumption of election night in the U.S. At that moment, Adam Masterson was reminded how easily some of our cultural icons are forgotten. “It was just the news flash in the middle of this election,” says the New York-based singer and songwriter. “These great artists leave, and then we’re just left with algorithms and playlists.”

Videos by American Songwriter

Immersed in the whole world of the ’60s counterculture and movements before his time, London-bred Masterson began writing his postcard to counterculture on “Bring Back the Freaks,” an homage to ones that came before a more branded, digitized world replanted art from its more grassroots.

“These artists, perhaps they weren’t changing the world, but they were definitely changing the consciousness and moving it forward in a way that felt healthy to where ‘wow people are sort of going somewhere,’” says Masterson. “Then they started exiting the building—Prince, David Bowie.”

Initially recorded live March 2020 at co-producer Craig Dreyer’s studio Mighty Toad studio in Brooklyn, New York, with drummer Charley Drayton (Bob Dylan), bassist Brett Bass, and Ben Stivers on piano and vibraphone, the song was later mixed by Paul Stacey at Realworld Studios in Bath, England, during the lockdown. “It was quite a spare of the moment collection of wonderful talents at quite an ominous moment for the world,” says Masterson of his ensemble, “recorded just in the nick of time.”

Relocating to the U.K. to ride out the pandemic, Masterson continued fine-tuning two additional songs from the session, “Wild Wolves” and “Trap Door Heart,” which were set for release in 2022, while adding finishing touches to “Bring Back the Freaks,” including a string arrangement by James Hallawell, which was tracked via Zoom.

Driven by the notions that the geeks have taken over the world, and the freaks—earlier cultural pioneers—have been forgotten (the mystic high priests whose voices have ceased), the song plays through some more questionable states and is a roll call of “rebels from the past,” name dropping the likes of John Lennon, David Bowie, occultist Aleister Crowley, and novelist Charles Bukowski.

“It all goes back to the freaks,” says Masterson, singing bring back the freaks.. where are our beautiful beasts. I can’t get used to you geeks. “When they were schoolboys, they were a little bit odd, and they grew up to be these sort of heroic figures just believing in themselves. You look around now, and there isn’t room for that anymore.”

“Bring Back the Freaks” also explores life evolving around a digitized and social media-driven world. “Our lives are increasingly more online, and it’s a paradigm that’s kind of designed for us,” says Masterson, who referenced producer T Bone Burnett’s take on the tunnel vision danger of being programmed in a digital world. “He was talking about how the ‘worldwide web’ was this really exciting moment for mankind, a great democratizing peer-to-peer simpatico, and this great interface where we could communicate, but it’s been taken over by six companies that guide our whole experience. It’s gotten to the point where if people want to get off Facebook, they don’t know where else to go.”

Life and art lean more on self-marketing and branding. “We’re becoming less Luddite as time goes by,” says Masterson. “Now, music and art are more about branding. Back then, the freaks had their own brand but they didn’t think about it in that way. They were just these naturally charismatic individuals. That bucks the trend today because branding people, they want to steal that cool. They don’t want someone coming into the situation that’s obtrusive to the branding.”

He adds, “We all buy into this convenience, but our world is being changed. Culture is more of an add-on, but it’s very healthy for our mentality and the psyche of all of us. Fragment is what we’re feeling now.”

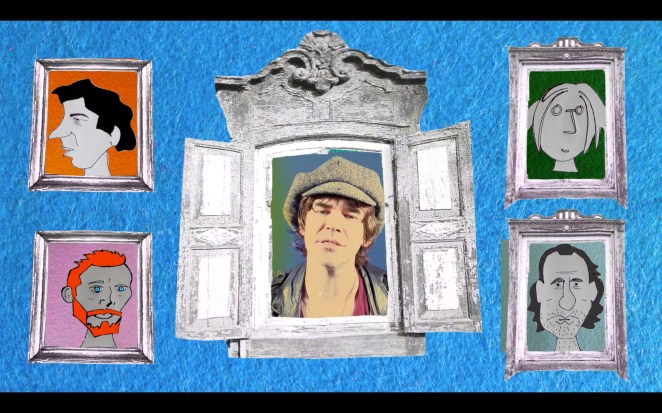

Visually, the video, animated by Callum Scott-Dyson, follows a character wandering through the many themes in the lyrics and ultimately depicts the power music has to unite.

“Music brings people together,” says Masterson, who is also releasing a holiday single “Don’t Be Alone on Christmas,” out Dec. 7, released as Greensmith & Masterson with all proceeds going to Save The Children.

“Some may say it’s a spiritual thing, but it’s certainly a thing that comes from their natural elemental source,” Masterson adds. “You’re engaging with someone, and it’s being given to you like a gift, like a blessing, and it’s humbling. The audience is connected, and this sort of engagement, it’s a very natural thing, and it sort of short circuits all we’re worrying about, what we’re thinking about, and tunes us out of that.”

Photo: Robert Ascroft