If anything were evident from the unrestrained and humorous stories covering up deeper anguish on her 2022 debut If My Wife Knew I’d Be Dead, it’s that CMAT’s inky humor has a knack for adding some jest around more catastrophic situations.

Videos by American Songwriter

On her sophomore release Crazymad, For Me, the Irish singer and songwriter even goes so far as to transport herself into a narrative of songs that is as much about herself, and the leftover pain from a toxic and damaging breakup seven years earlier as it is about the listener. At its core, CMAT—the artist’s acronym for her real name Ciara Mary-Alice Thompson, and not the academic mathematical test—has crafted a breakup album that flutters through beautifully brandished country-pop.

Recorded, produced, and mixed by Matias Tellez at his studio in Bergen, Norway in early 2023, the 12-track Crazymad, For Me follows CMAT’s three-fold storyline through her own sardonic means, from the opening “California,” where the story kicks off: I’m working on a wreckage / With nothing there to salvage / Oh, I’m just taking photos / For my book about the damage and / Some have called me cheap / But it’s not that fucking deep.

Dubbing Crazymad, For Me—a title pulled from Sheena Easton’s 1981 hit “Morning Train”— her “’Bat Out of Hell’ by Meatloaf for the girls,” CMAT delivers the perfect blend of country, anthemic pop, and some indie swagger. She was a good girl, so I pay the price / I have to stay broken to be worth your nights sings CMAT on the more indie-bent, Sex and the City-inspired “Such a Miranda.”

John Grant joins CMAT on the nostalgia-webbed “Where Are Your Kids Tonight?” a song CMAT revealed she wrote when she realized she turned into her mother while owning up to her own self-sabotaging proclivities on the soulful confessional “Can’t Make Up My Mind,” and Kate Bush-brushed “I Hate Who I Am When I’m Horny.”

For CMAT, who went to No. 1 in Ireland with If My Wife Knew I’d Be Dead and won the RTE Choice Music Prize—Ireland’s equivalent to the Grammys—this is just the beginning of an anthology of more stories she’s ready to tell.

CMAT spoke to American Songwriter about writing through heartbreak, and how Sheena Easton inspired Crazymad, For Me.

American Songwriter: When did Crazymad, For Me Start coming together since If My Wife Knew I’d Be Dead? Were you working through some of the songs for both simultaneously?

CMAT: It wasn’t entirely a fresh batch. I did write quite a lot of new songs over the course of the year between the first record and the second. Some songs from when I was making the first record, I knew they were good, but I specifically didn’t want to put them on this album. I’d always had the idea that for my first record, I was not going to mention anything about a specific relationship that I was in because the person that I was in that relationship with, I was in a band with. I wanted my first musical venture to not have anything to do with him or any of that music.

AS: Sheena Easton also helped with the overarching storyline. Why was Crazymad, For Me the perfect title for this collection of songs?

C: I love Sheena Easton. I think she’s so fucking great. She’s my favorite vocalist—ever. She’s such a voice, and she’s got this song called “Morning Train” (also called “9 to 5”). I thought that that song was a really good analogy for this entire record because that song was made in the 1980s and the text is around this young girl who just got married. She lives at home with her husband, and she sits all day waiting for him to come home every single day.

I sit at home all day waiting for him to come back because I love him so much. All the time. And then he comes home, and we have sex all night. That’s what that song is, which in the context of the 1980s [may] sound romantic and lovely.

If you read it today, that’s a horror story. That’s a terrible way for women to live, so I thought it was a really good analogy for the whole album because the record is about a relationship that I was in when I was 19. And at the time, I thought “This is so romantic, amazing, beautiful, perfect, and wonderful.” And now I’m 27, and I look back on it like “What the fuck was that? That was terrible.”

The line in question—All day I think of him, dreamin’ of him constantly / I’m crazy mad for him and he’s crazy mad for me—really summed it up, because it can be read both ways. I think of him all day, or I’m extremely fixated on this person, and I have to think of them all day, every day, and it’s not healthy.

AS: Your past relationship in question happened years ago. Why did you need to confront it now on this album?

C: The point of writing a breakup album six or seven years after it happened is that you can actually have a decent bit of perspective on it. I don’t think I could have written it beforehand. I needed to release another album first. I needed time to have more perspective on it. When I was going into the songwriting sessions for this album, I thought it was going to be this forgiveness record, of loving everyone, even after you’ve stopped loving them. As I actually went into writing it, I just found myself getting angry again.

I was thinking “Why have I not moved on? Why is this still annoying me as much as it did seven years ago?” The reason is that healing is not linear. Time is not even that linear, but it does give you more perspective. When you’re stuck in a trauma, or in a series of events that fucked you up, it’s kind of like time travel. You can be doing the dishes or [vacuuming], or something really normal, and then you’ll remember a five-minute incident that happened seven years ago, and for that 30-second or two minutes you’re still really angry about it.

That specific feeling is the thing I’m trying to illustrate on the entire record. This is a breakup album, but it’s not necessarily an album of that person or that relationship but more about the structure that those events gave to me figuring out things.

AS: Initially, you had more of a structured concept album around time travel, going back to the 1890s and other eras. What made you dial this back a bit?

C: The record is in three parts. I got rid of the narrative and more concept pieces because I thought that it was stronger to have just 12 really good songs straight down with nothing getting in the way of them. I was also using the narrative and the concept to bump the edges off what I was actually doing. I was trying to not be literal so people wouldn’t know who I was talking about. I was quite embarrassed being as autobiographical as I have been on this record compared to the last one. Eventually, I just took all that shit out because I needed to be a little bit braver and suck it up.

People find my stuff very relatable because it’s very specific and very descriptive, so I wanted to—in the nicest way possible—respectfully use that against the listener. The first third of the record, which is the first song (“California”) up until “Rent,” is basically the “poor me” section, like “He was a bastard, and I’ve never done anything wrong.” Then the middle section is a setup where I start talking about all the things I did wrong in great detail, specifically with “I Hate Who I Am When I’m Horny.”

I really make a point in that section of the record to make myself look bad, because I liked the idea of someone listening to it and [finding it] relatable … forcing them to acknowledge that if they related to me in the first bit of the record then maybe they also relate to me in the middle where I make myself look bad on purpose. The third section, from “Torn Apart” to the end (“Have Fun!”) is specifically set up as a resolution, but it also illustrates the point that you can’t really make sense of things that have happened.

AS: This is definitely not a “typical” breakup album.

C: One thing I particularly hate about breakup records as an institution is that whole [adage] “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” or “If the Lord lead me to it, then the Lord can lead me through it.” That kind of narrative you get a lot in popular culture, which is that if you suffer through something it makes you a better person. I think the whole point of the last third of the record is me saying that is not true. Suffering is suffering. Pain is pain, and it’s just something that happens. You just have to move on to the next thing. It’s not something that makes you better, and it’s not something you can use to justify any bad actions.

I think there’s a lot of “trauma music” happening right now and a lot of breakup music, but I don’t like the notion of “Something bad happened to me, therefore, I get to be a victim for the rest of my life,” or “I get to use it as an excuse to be a dickhead to other people or feel entitled to other people’s attention.”

I try to make myself look really bad on this record so that anyone who found me relatable would maybe question their own shit. Being a songwriter, I have flashes of lucidity, and that’s generally what I try to capture.

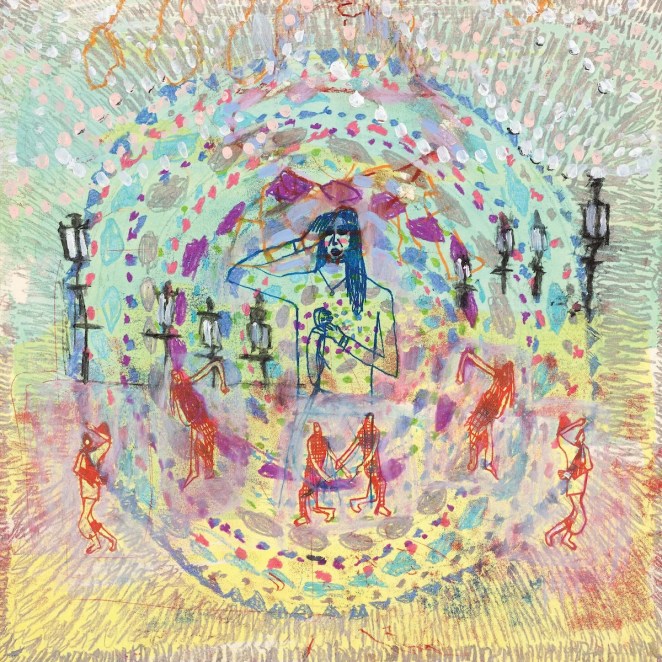

Photos: Sarah Doyle / Courtesy of Shore Fire Media