On Simon & Garfunkel as kids, as Tom & Jerry, discovering Dylan and the arrival of “Sound of Silence”

“What happened,” he said, “is I fell in love with echo chambers.” That is Garfunkel speaking, Artie, as he’s known. We had a big conversation a few weeks back, with an invitation to talk during the lockdown about how he’s getting through just for a few minutes. It blossomed into a conversation of almost two hours, during which he sang, line by line, through some of their most famous songs, and analyzed them.

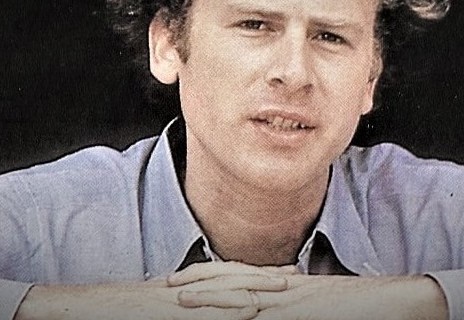

In advance of that conversation, which will be in three-parts, we wanted to first bring this, an introduction to Artie and his history with his friend Paul Simon, becoming a pop duo with cartoon names singing in perfect harmony. It leads to when they started using their own names, and sang of silence instead of schoolgirls. From that moment on, things changed in a big way.

Videos by American Songwriter

Old friends

Winter companions, the old men

Lost in their overcoats

Waiting for the sun

It starts so softly, two quiet chords taking turns, and then Simon alone singing “old friends sat on their park bench like bookends. . .” before he’s joined in harmony by his oldest of friends, Art Garfunkel, on the line, “Lost in their overcoats waiting for the sunset. . .”

Later Garfunkel takes his turn, and sings alone “Can you imagine us years from today sharing a park bench quietly?”

From Simon & Garfunkel’s landmark Bookends album, “Old Friends” is a song, like most of their work, which continues to resound long after the record is over, like an echo without end.

Art Garfunkel first experimented with echo when he was a kid, singing in the synagogue and the halls of his school. From an early age he recognized the almost holy quality of his own voice: an angelic, ethereal sound that excited his own ears before the rest of the world ever heard it.

“I learned how to sing with Artie, ” Paul Simon told us. “My voice was the one that went with that voice.” That Simon and Garfunkel grew up only blocks from each other in Queens, New York, and attended the same school is one of those enormously lucky twists of fate; lucky not only for the two of them, providing each with a counterpart in harmony both musical and personal, but for the world at large, who have been blessed by the magical sound of these two voices together .

Inspired by the Everly Brothers, Paul and Artie’s voices blended as if the belonged to brothers; listen today to “Scarborough Fair, ” “The Boxer,” “Homeward Bound” or any of their other classic duets, and experience a sensation that was especially soothing in the turmoil of the sixties, and resonates today every bit as powerfully, the sound of two voices singing from a shared soul.

It’s a sound that their engineer and producer Roy Halee said couldn’t be achieved when they separately overdubbed their vocal parts onto tape. But when Simon & Garfunkel sang together at the same time, it was magic.

They met backstage in a school production of Alice In Wonderland, but even before that Simon was intrigued by this tall, curly headed kid who could impress the girls with the sweetest and smoothest of singing voices. They teamed up as teens and at that tender age rehearsed like professionals, developing a miraculous precision and harmonic blend.

Adopting the names of cartoon characters , Tom & Jerry, which seemed much more pop-friendly than the unwieldy “Simon & Garfunkel,” they entered the world of rock & roll at fifteen with a song they wrote together and recorded called “Hey Schoolgirl.”

The song was a hit and the duo began to live out their dreams while still dreaming them, appearing on Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand” as high schoolers. When their next song failed to fly, the duo broke up for the first of many times, and Tom became Artie again, and returned to the idea of a career in teaching.

In a different world, Art Garfunkel might have gone on to become a professor of Mathematics, quietly and contentedly aiming his enthusiasm for numbers at a classroom blackboard instead of at the Hit Parade. But through a series of twists and turns, most of which are detailed in ensuing conversations, Garfunkel teamed up many more times with his childhood friend, and made some music that changed the world.

Though he was never really comfortable performing in front of people, he recognized that in the recording studio he could bring his voice to a state of pure grace, a kind of perfection preserved forever in his spiritual singing on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” and so many others.

The partnership of Simon and Garfunkel, despite well- known accounts of their squabbles and differences, stands today as evidence of the power of real friendship; Garfunkel’s perfect harmonies added a depth and richness to Simon’s songs, while Simon continued to grow in his writing and provide Garfunkel with the greatest material a singer could ask for.

When their time came to an end, and Artie was away in Mexico shooting Catch-22, the songs that Simon wrote reflected the sadness of their separation, two of the sweetest and most enduring songs of friendship ever written, “The Only Living Boy In New York” and “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright. “

As a solo artist, Garfunkel turned to the songs of some of the other great writers of our time, including Randy Newman and Jimmy Webb. Webb wrote “All I Know”, a soaring love song rooted in the gospel passion of the Baptist church ideal for Garfunkel’s angelic voice. It was the first hit from his debut album Angel Clare, which also featured an impassioned interpretation of Randy Newman’s “Old Man.” Garfunkel’s entire Watermark album was devoted to Jimmy Webb songs new and old, and it’s a treasure, featuring a heartbreaking rendering of Webb’s “Wooden Planes”.

He’s also a man of many other talents. Besides acting in films from Carnal Knowledge through Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing, A Sensual Obsession, he’s also an excellent poet, having written a book of 84 inventive and poignant prose poems called Still Water, which was published by E.P. Dutton (now New American Library) in September of 1989.

“I have to warn you,” he told me in advance of our first interview in 1992, “Simon and Garfunkel was twenty years ago. I may not remember that much about my old group.”

“We human beings are tuned such that we crave great melody and great lyrics. If somebody writes a great song, it’s timeless, in that we as humans are going to feel something for that forever.”

Art Garfunkel: What happened was I fell in love with echo chambers. All the kids would be let out of school and you’d be at the back of the line. And you’d be humming something to yourself and the kids would go ahead, and you’d be in the stairwell with all those tiles. And I’d start singing and it would sound really nice in the tiles.

So everybody would go home and I would linger. And sing for about an hour or so. And I remember thinking, [laughs] “This is a really nice voice coming out of my throat.”

I was really digging the tiles but I did have a lucky thing going on there in my throat.

[Singing] is a God-given talent, and I observed that I had it at a very young age, maybe five or so. My parents both sang very casually around the house. My family bought a wire recorder in the forties when I grew up, and they would sing a little into the wire recorder. Not seriously but just to make music around the house, and I must have liked the pleasing sound and their harmony.

There was a little singing in my childhood and I could do that myself, I realized. The next thing I knew is, with a little bit of practice walking to school; you know how when you’re walking on the pavement and you hit the cracks, you can get a song going to your walking step? Well, I used to sing and when there was no one around, I could sing pretty loudly, and I thought I had a nice voice.

So I would sing a song and then start again at the top and push the key a whole tone higher. I remember doing this as a young child. I must have been training. Taking this serious attitude.

Songs I had heard on the radio. This was the Perry Coma era. Schmaltzy ballads. Plus there were certain inspirational songs that would get to me: “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Carousel. Stuff with the goose-bumps used to get to me. And I would sing those.

And then I would sing a little in the synagogue. See, if you’re a singer, you love to turn your own ears on. You look for those rooms where the reverb is great. I remember the synagogue had a lot of wood and it was a great room. And it was a captive audience and you could sing these minor key songs and make them cry, and that was a thrill.

Then I would sing in grade-school when I was about eight. I bitched onto Nat King Cole’s hit, “Too Young.” [Sings] “They tried to tell us we’re too young. . . ” That was my song and I was totally identified with that. I sang it in the school talent show and got popular with the girls that way.

That got me a little into stage experience. They cast me in a play about Stephen Foster. I played Stephen Foster and sang “I Dream Of Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair” and some other Stephen Foster tunes.

I remember singing, [sings] “…a beautiful sight, we’re happy tonight…” [ “Winter Wonderland”] They cast me in some Christmas thing so I sang that.

Paul Simon grew up three blocks from me but I didn’t know him. He said, “I could see you in these talent shows in the 4th Grade.”

By the sixth grade we met each other because we were both cast in the school graduation program, Alice In Wonderland. And he was the White Rabbit and I was the Cheshire Cat. There was no singing in that play but there was a lot of [laughs] humor and joking around and a really fast new friendship between the two of us backstage. So we became best buddies.

Paul could see singing was a means to popularity. That was the way you got to be known and he thought it was cool. And he’d seen me in the hall. “There’s that guy who sings.” And I would sing sometimes at the Jewish High Holiday services.

When Paul and I were first friends, starting in the sixth grade and seventh grade, we would sing a little together and we would make up radio shows and become disc jockeys on our home wire recorder.

And then came rock & roll. The very phrase was born through the mouth of Alan Freed as we were junior high schoolers. And when we listened to that subversive, dirty, rhythm and blues music on the radio, we know that was the cool stuff. It was the only thing in American society, aside from baseball, that had real genuine appeal and was not hype-y.

So we emulated the songs and practiced sounding like them and we tried to have our own record, and we knew we were going to try to get on a label, and we would work on our harmonies. And then we got remarkably serious in our rehearsals . We would have sessions that were so much about accuracy and patience and repetition and study.

I would sit and examine exactly how Paul says his ‘T’s at the end of words Like ‘start.’ And where would the tongue hit the palette exactly. And we would be real masters of precision, figuring this would be the way to make it sound slick and tight and professional.

Doing harmonies came pretty naturally. I’m the kind of person who can hear that stuff. If you sing along to the radio and you’re not going to sing unison with the melody, but find the harmony, I find that pretty easy to do.

Then came the magic words “Everly Brothers.” When they hit the radio with “Bye Bye Love,” we were really off and away. They killed us and we thought that was the coolest sound. We used to wait for their records to come out.

So I think you can hear that they were a tremendous influence on us and on so many people. This nation should prize them as one of the great treasures of our musical history. Those guys were extraordinary. Not only because they were so damn good. but they were so cool; their sound was so neat, and so unlike anyone else.

The song seems to ask for the harmony. You do two things: You try not to repeat yourself, you shake up the formula and observe what the song and the lyric and the arrangement seems to call for.

We do that on “Sounds of Silence.” I sing the melody. We pitched the song fairly high because I’m a tenor. That left Paul below me, looking for a harmony part.

I remember the first time I heard “Sound of Silence.” We were in my kitchen in my apartment on Amsterdam Avenue, uptown in Manhattan, when I was a student at Columbia College, in the Architecture school.

Paul would drive in from Queens, showing me these new songs. And that was the sixth song he had written, “Sound of Silence.”

He showed it to me in my kitchen and I went crazy for how cool it was. I don’t remember us saying, “Who’ll do melody?”

I think it’s fair to say, he was so impressed with Dylan. As was I. To the extreme. Dylan was the coolest thing in the country.

If you were a young person at that age, maybe you don’t go for Dylan’s gravelly style voice, but who he was and how different and bold his lyrics were, and his look, that was the closest thing the record business had to James Dean. His album covers, if you look at the early Dylan, you see a real charismatic choir boy star of a kid.

I remember when Freewheelin Bob Dylan came out, his second CBS album, I was in Berkeley. I was a carpenter. This was my year off from architecture school getting field experience And I was singing at Berkeley in clubs as well as doing carpentry during the day.

I saw in the record store around early September the new Freewheelin‘ album. And there’s Dylan in the village walking in the snow, and the camera’s got an upward angle on him and he’s with his girlfriend. And I knew I had to try and make another record. [Laughs] That was such a great place to be!

So I came back home [to New York], ran into Paul, he showed me these new songs he had written, about two or three songs. And they were really wonderful. And I let him know how keen I was to work out harmonies for them. In my mind I was thinking, “This has got to make it now. Between the commerciality of these folky songs that Paul’s writing, and the blend that we had worked on in the past, which will now serve us, we should have a shot at a career.”

END of PART ONE.